Naming of the shrew: What's in a scientific name?

- Published

Every new species is given a scientific name that is recognised and understood by scientists all over the globe

What's in a name? If you happen to be a taxonomist then the answer is probably quite a lot.

For a scholar, species' scientific names - the ones that are, for most of us, impossible to spell and just as hard to pronounce - help unlock a whole new world.

As well as unlocking centuries of scientific endeavour to discover and describe the planet's biological bounties, the italicised Latin names also provide a gateway into a literal and descriptive lexicon of life.

"I would say most of the Latin names are descriptive and would say that it is the commonest form," explained fungi expert John Wright.

"Historically, they were descriptions and could be very long to say - for example - the furry oak tree that grows on mountains (the system was known as polynomial).

"Now, it would probably be shortened to Quercus pubescens, but even the shortened binomial is still descriptive - it tells you the oak (Quercus) has hairy leaves (pubescens).

"There is a real satisfaction to be gained from finding out what the Latin name means because it is a puzzle solved."

Naming of the shrew

And it was this sense of satisfaction that has led the lifelong Latin lover to write a book, The Naming of the Shrew, which has been published by Bloomsbury.

In the 18th Century, it became clear that a new system for naming species was needed

"Names are just letters and sounds, but if you know the Latin name then you have the true name," he told BBC News.

"I knew that some of them were lovely and I began to collect them," Mr Wright recalled.

"I felt like it was a book that needed to be done as people are frightened of Latin names and find them very off-putting. It creates a barrier between them and the natural world, which is such a pity.

"Latin names often do make sense and they do have meaning, some of them are glorious."

New species are being discovered all the time, so when scientists describe the organism for the first time, the scientific name can take its inspiration from some unlikely quarters, such as popular culture.

One example is Aptostichus sarlacc.

Mr Wright explained: "A sarlacc, in the film Star Wars, was a thing that that lived underground and if you fell into its hole then you would just be digested slowly, but it is the Latin name of a trapdoor spider."

Contemporary but still descriptive.

Another example is Albunea groeningi, a sand crab named after Matt Groening, creator of TV cartoon The Simpsons. Why? The newly described crab species was pale yellow.

But the one that takes some beating is Apopyllus now, a species of spider named shortly after the blockbuster film was released.

A rose by any other name

Mark Spencer, honorary curator of the Linnean herbarium, explained that the method for naming species - known as the binomial system - provided an "intellectual hook all of the information we know about the natural world".

"It is a place where we can attach information about the organism's distribution, its medicinal properties, its agricultural uses, what it's related to - all of these that are tied to it as a living thing are tied to its name," he told BBC News.

The continued use of Latinised names was for convenience, he explained.

"The roots of using Latin go back into the history of western literature, and Latin was used for centuries as the language of scientific communication," Dr Spencer added.

"It was classically taught to all school kids and university graduates across Europe so it was a common language that everyone understood. Its roots are deep in European cultural history."

The binomial system consists of two parts: the first is the name of the genus or group to which the organism belongs, while the second part is the name that distinguishes the organism from other species within the genus.

This naming convention can be traced back to the mid-18th Century and a Swedish doctor called Carl Linneanus.

He developed the binomial system as a short "common name" that would act as a memory aid to the long polynomial "correct" name.

However, it proved so popular that the short names were quickly adopted as the correct name and the inconsistent and clumsier polynomial system fell out of use.

Today, the universal naming system is essential for more than just scientists.

Dr Spencer observed: "The system also ultimately underpins international commerce and international legislation because without the application of the scientific names, things like Cites (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) would be at sea because all sorts of names will be in use and who would understand what is what?

"International trade laws around things like bio-piracy, pharmaceuticals and agriculture - you name it - are underpinned by the science."

Following the code

As well as being given a descriptive name, the rules that set out the process of an organism being recognised as a new species - known as the Code - species can be named after the place they were first found, or after a person.

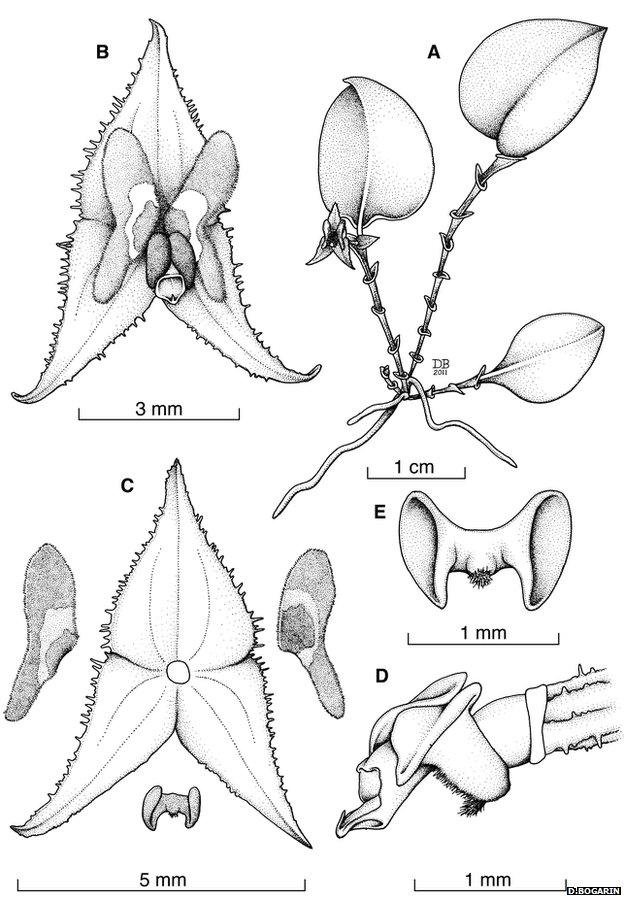

Botanist Kath Castillo from the Natural History Museum, London, is someone who has had a species named after her. In her case, a tiny tree-dwelling orchid.

"I was working as a field assistant for Yael Kisel, who is a macro evolutionary biologist, and we went to Costa Rica in 2009," she recalled.

"We were collecting study species for her population genetics study. Among those species were two species of Lepanthes. I was searching for those two species when I discovered a very small population of a Lepanthes species in a rainforest reserve, and it turned out to be a new species.

She told BBC News that spotting the new species, now known as Lepanthes castilloae, was a combination of "luck and experience".

"When you are a field biologist, you are looking for structure and shape in a backdrop of many other structures and shapes.

"This search for structure and shape was key in discovering this little orchid because I saw it on the branches of quite a low level tree, and I looked at it and thought that it was probably Lepanthes but I could not tell whether it was a species I was after because it was not flowering and the leaf shape was a bit different so I decided to collect it.

Dr Castillo observed: "Traditionally, species have been named by taxonomists to record a number of things, such as its external appearance, its place of origin or as a dedication to a person, often the discoverer.

"So it is probably not as useful in a way. Personally, it is very nice and professionally, it is an acknowledgement of my contribution to science."

John Wright explained the delight that awaits someone who takes the time and trouble to unlock the true meaning behind a Latinised scientific name.

"My proudest achievement was Inocybe eutheles," he recalled. "The prefix, eu, is Greek for good, true or nice.

"The species is a fibrecap mushroom, and I found a picture of it. It was rounded, cream coloured with a little point on the top. I thought eutheles meant good or true or nice something but I wondered what theles meant. I discovered it meant nice tits - a 19th Century mycologist came up with that name.

"I was very proud when I unearthed that one because I do not think anyone else realised what it meant."

Botanical illustration of Lepanthes castilloae, which records the visual characteristics of the tiny orchid species

- Published15 February 2013

- Published23 August 2011