History beckons for Rosetta comet mission

- Published

A first for space exploration: No probe has previously made a soft touchdown on a comet

All is on course for Wednesday's ambitious attempt to put a probe on the surface of a comet.

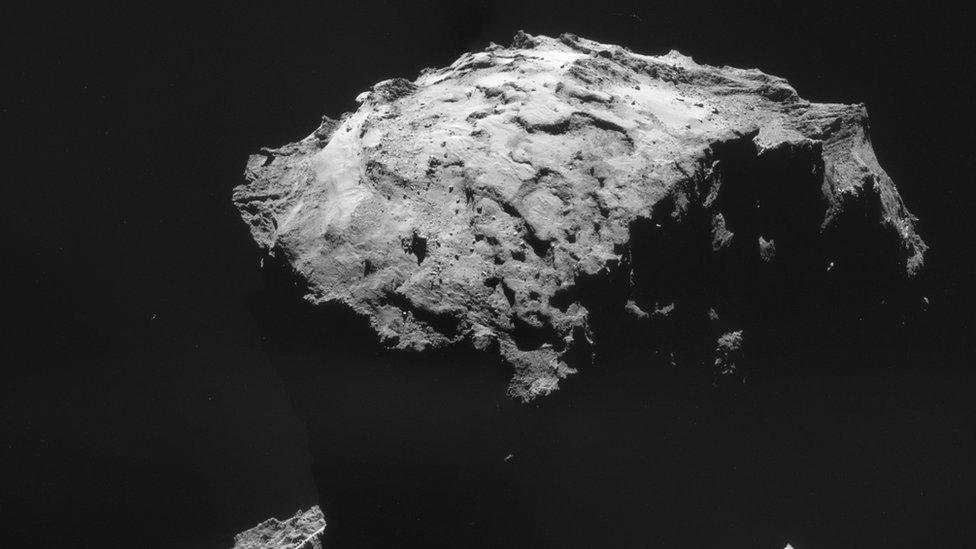

Europe's Rosetta spacecraft, external is currently making a long arc around 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Shortly after 06:00 GMT, the orbiter will make a sharp turn towards the ice mountain, accelerate, and then eject the Philae robot towards its target.

Separation should occur at about 08:35 GMT. Touchdown is expected roughly seven hours later.

There is a series of major decision points in the run-up to the ejection - what the controllers back here on Earth call Go/No-go decisions.

It is at these moments that the flight team at the European Space Agency's operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany, will assess progress and choose either to move forward to the next pinch point, or to abort and regroup for a second landing attempt in a couple of weeks' time.

At each Go/No-go, the controllers will be paying particular attention to the navigation accuracy of Rosetta as it swoops over the comet to deliver the Philae lander.

The critical one, of course, is the final decision point, when the team receives telemetry from Rosetta describing the performance of that earlier sharp turn.

"We will get a radio signal from the spacecraft that will tell us whether or not our last manoeuvre was successful, within the right accuracy," says Paolo Ferri, the head of operations in Darmstadt.

"It's a very small piece of information, and we then have very little time to react, because very soon we have to send an instruction to Rosetta, 'yes, you're go for separation of the lander, or not'. This critical decision point, with little information and little time, worries me a lot."

Three spindles driven by a common belt will release Philae from Rosetta with a velocity of 18cm per second.

If for some reason the spindle system fails to operate, a back-up spring mechanism is automatically primed to fire to ensure the robot is booted off come what may.

"The timing is extremely important, and also where we release the lander," explains flight director Andrea Accomazzo.

"We have to predict the position at that point to within a few tens of metres or we land somewhere else on the comet or we don't land at all.

"And the velocity of Rosetta - we need to know to a few millimetres per second. These are the two parameters we have to control very, very accurately.

"Once this is done then the lander will fall on to the trajectory we have predicted."

The Philae robot is pushed off Rosetta by means of spindles

On separation, mothership and lander will be out of contact because the umbilical cable that has joined them for the past 10 years will have been dropped in the ejection process.

Controllers will have some idea of their relative positions, however, because a range-finder system will have been activated.

But proper radio communication has to wait until after Rosetta has performed another trajectory change - one that takes it away from the comet and on to a path where it can maintain good radio "visibility" to the descending Philae over a longer period of time.

Establishing radio contact two hours after separation is another of those high anxiety moments.

"If we pick up this signal, no matter what happens on the surface, we will have pictures on the descent and we will have measurements during the descent," says Paolo Ferri.

"Even if then at the touchdown Philae does not survive, we would have had a significant success all through this descent phase.

"So, the reception of the signal by Rosetta from the lander roughly two hours after separation is for me one of the most critical moments, also."

We should get a couple of "goodbye" shots from Philae looking back towards Rosetta. They will be iconic images for sure, but they have an engineering significance also because they will tell controllers something about the stability and attitude of the robot as it came off the side of Rosetta.

There should be some downward-looking images also, pulled from the Rolis camera system on Philae.

These will show the approaching comet, and, again, they contain important information about where the lander is headed - information that can be allied to maps of the comet to try to find the robot in the event of a failure at touchdown.

That should occur at just after 15:30 GMT, space time. But because of the 510 million km between Earth and 67P, external, we won't know the outcome until a radio signal arrives almost 30 minutes later. The minutes around 16:00 GMT are when we should find out whether history has been made.

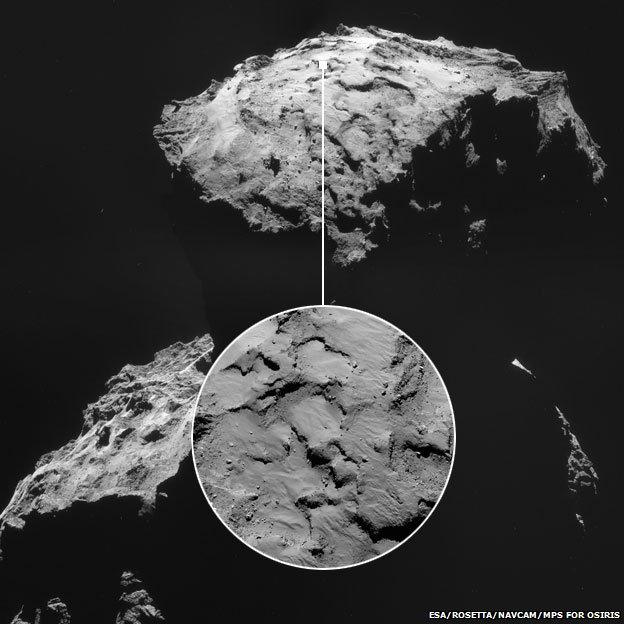

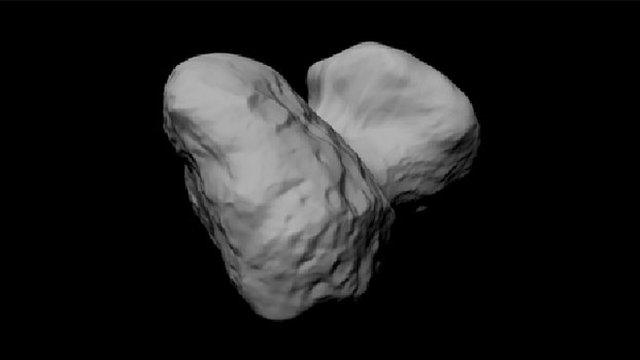

The targeted landing site is on the head of the 4km-wide rubber duck-shaped comet

- Published17 June 2015

- Published4 November 2014

- Published24 October 2014

- Published17 October 2014

- Published24 October 2014

- Published14 October 2014

- Published3 October 2014

- Published7 August 2014