Mars rover goes after carbon clues

- Published

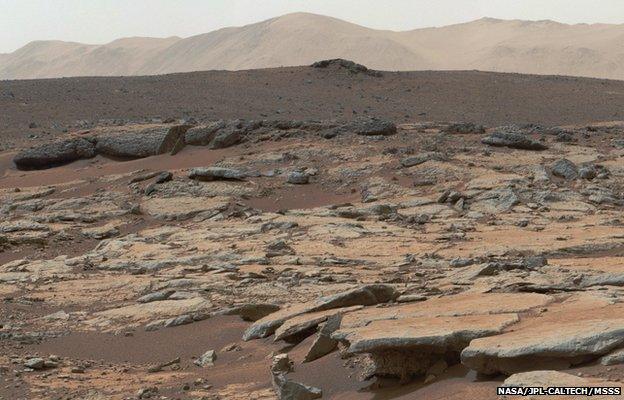

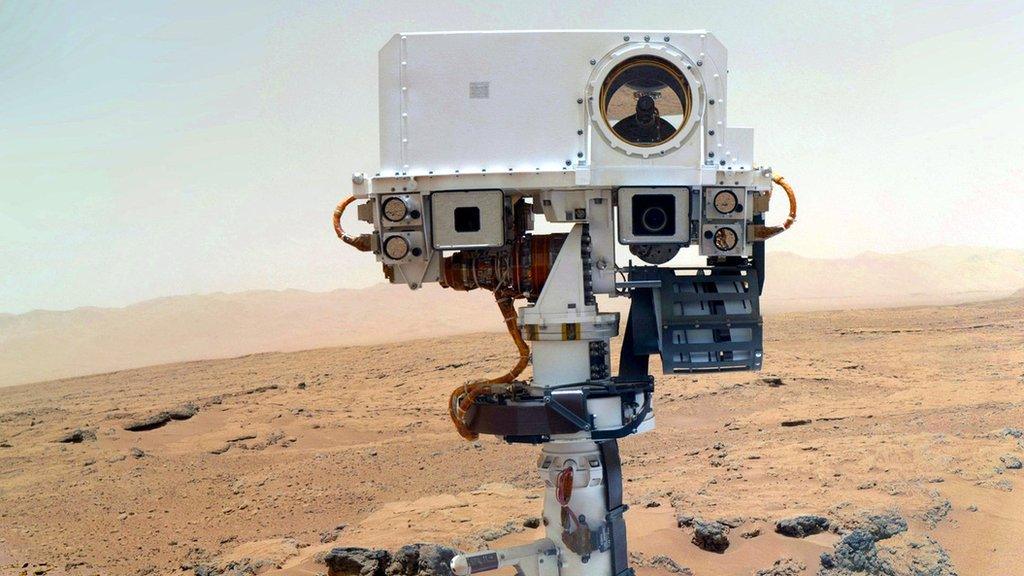

Newly eroded surfaces - seen here in front of the overhang - are the prime locations for the organics hunt

The team operating Nasa's Curiosity rover is implementing a new exploration strategy on the Red Planet.

Having established that the ancient environment at the robot's landing site was once habitable for certain types of microbe, the scientists now want to focus on specific questions relating to life.

In particular, the rover is ramping up its hunt for organic molecules.

Life as we know it trades on these carbon-rich structures.

Finding them would not be proof that organisms ever existed on Mars, but it would certainly inform discussion on the subject, Curiosity project scientist Prof John Grotzinger told BBC News.

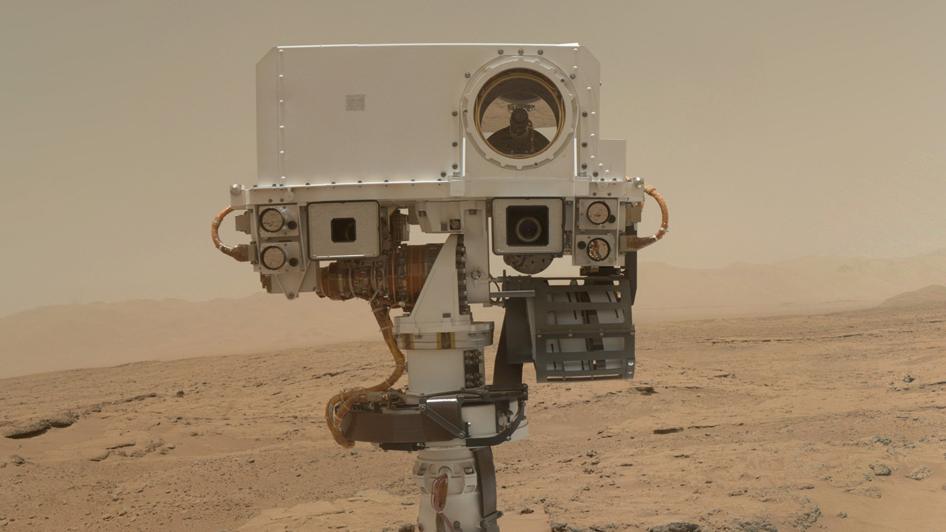

John Grotzinger: “We’ve reached a turning point in the mission”

"If you go back to rocks that are billions of years old on Earth, for soft-bodied, single-celled micro-organisms, it's very, very rare to find an actual fossil of the micro-organism.

"What you usually find, and it's also quite rare, are organic remnants of the molecules. So, the cell wall breaks down, it fragments and it leaves behind large organic molecules that betray the existence of life," he explained.

"The trick has always been to find these 'windows of preservation' where everything went just right and you peer beneath all the complexity to actually find something that's a bit of a needle in a haystack."

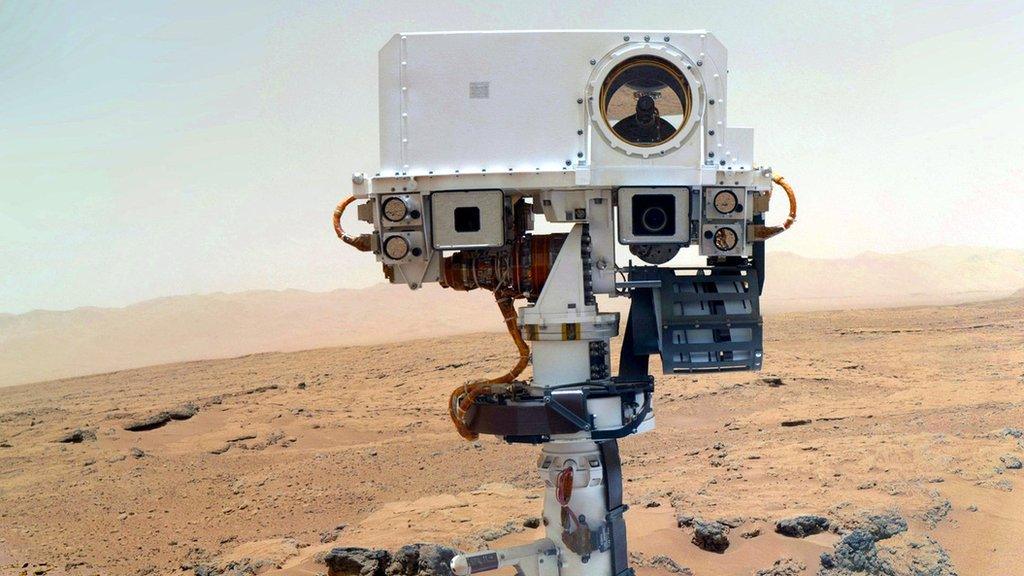

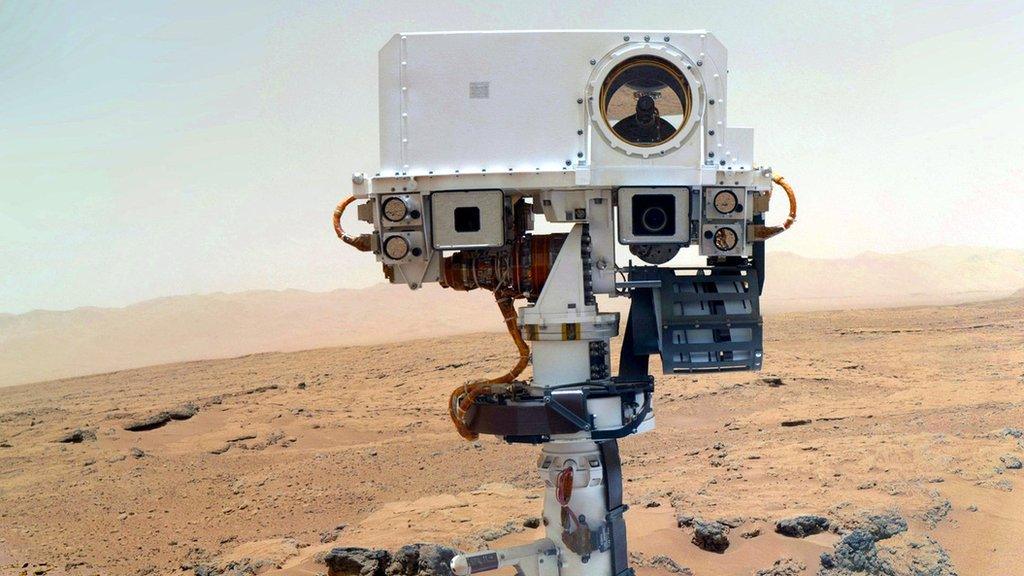

Ken Farley: “The dating tells us something about organic preservation”

Prof Grotzinger was speaking here in San Francisco at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, external, the largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary researchers.

The hunt for organics is a difficult quest because they are broken down over time by cosmic rays, the energetic particles from space that constantly rain down on the Martian surface.

Over billions of years, the chemical signature is destroyed, and it is thought only deep burial permits long-term preservation.

KMS9: The rover will soon arrive at a location where wind is eroding the surface (arrows)

But the Curiosity team thinks it now has an approach that will increase its chances of finding some relatively intact molecules. It plans to put this technique into practice in the next couple of months when the robot arrives at a new rock outcrop in Gale Crater called KMS9.

Assuming close-up inspection shows the site to be favourable, the rover will drill the sediments and deliver powdered samples to its onboard laboratory for analysis.

The switch in strategy has been prompted by two pieces of research.

One is the improved understanding of the cosmic ray environment on Mars obtained by the rover's instrumentation. This tells the scientists the sorts of timescales over which organic chemistry could withstand the radiation assault if exposed near the surface.

The second is the remarkable work done by Curiosity to date the rocks in Gale Crater.

This has enabled the science team to identify those surfaces that have only recently been exhumed through erosion, and are therefore most likely still to retain the organics signature.

What this all means is that Curiosity must drill just in front of "scarp" features on the landscape.

These are places where the abrasive action of the wind has only recently dug into the rock to uncover fresh material.

On satellite imagery, KMS9 looks to have just the right scarp features.

Already, Curiosity has shown the ancient lake environment in Gale would have been habitable

Curiosity scientist Prof Ken Farley, from Caltech, said: "Our observation gives us a strategy for minimising the cosmic ray dose by specifically looking at scarps that are exposing rock newly to the surface of Mars, and we believe we can get surface-exposure ages that might be about a million years. And in such rocks we expect that the organic preservation will be high."

The scientists caution that finding complex carbon chemistry is not a simple indication of past life; there are plenty of non-biological processes that will produce organics also.

In addition, making the detection in the robot's onboard laboratory is not straightforward. As scientists have discovered, there are other chemical components in the dust and rocks of Mars that will mask the presence of organics.

But getting a positive result would be a Eureka moment for the mission and a first for Mars exploration.

"Everybody wants to know - did life ever exist on Mars? How are we going to address that? Well, we need to go and look for biosignatures, or things that we think are evidence of life. Organics are part of life and therefore organics are part of that story," said Dr Jennifer Eigenbrode from Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published9 December 2013

- Published26 September 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published6 August 2013

- Published10 July 2013

- Published31 May 2013

- Published30 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 April 2013