Mars lake 'much like early Earth'

- Published

The scientists have provided additional details that should lend credibility to the earlier claims

The ancient lake environment found in Mars' Gale Crater could have supported microbes called chemolithoautotrophs - if they had been present.

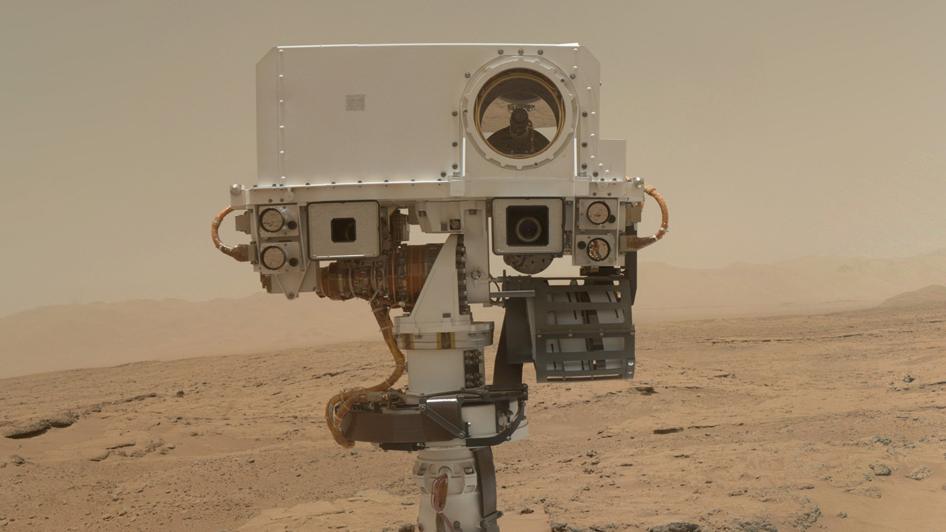

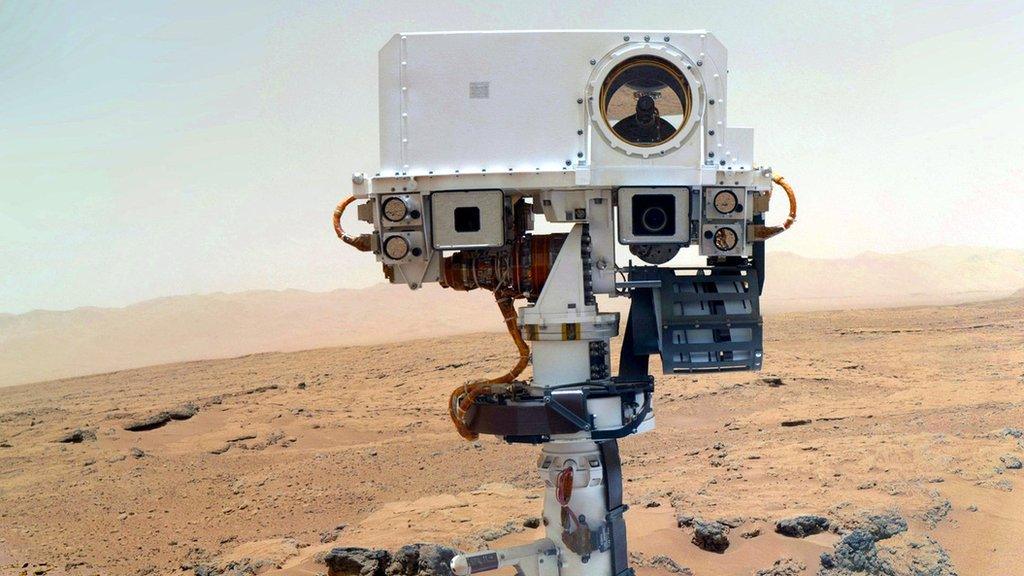

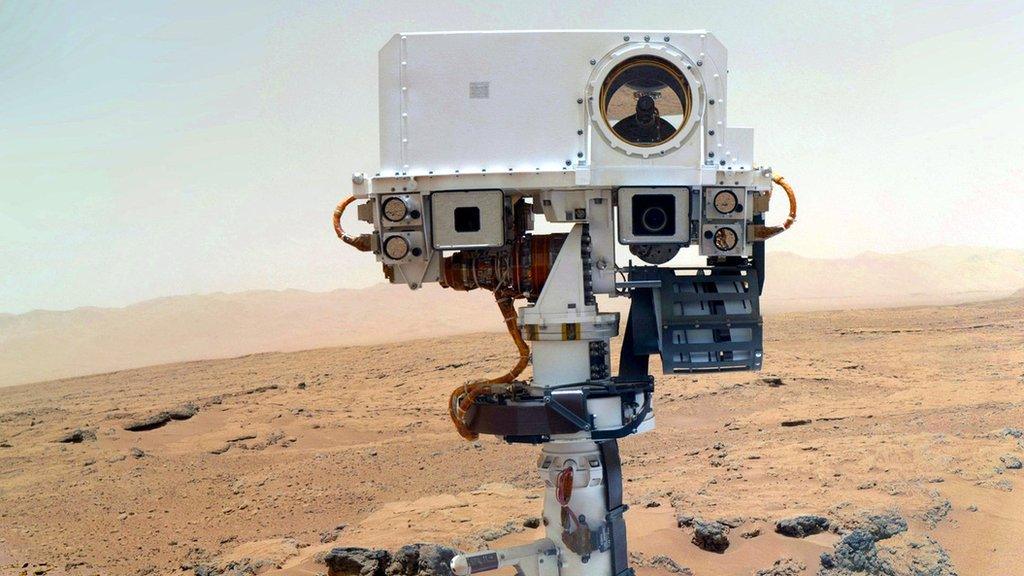

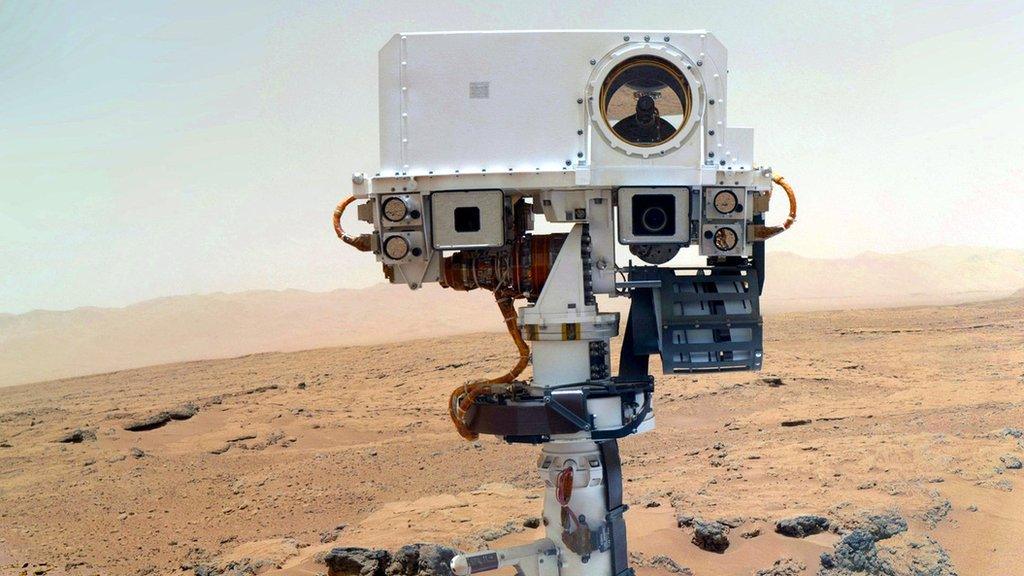

That is the conclusion of scientists after reviewing all the pictures and other data gathered in the deep impact bowl by Nasa's Curiosity rover, external.

Chemolithoautotrophs do not need light to function; instead, they break down rocks and minerals for energy.

On Earth, they exist underground, in caves and at the bottom of the ocean.

In Mars' Gale Crater, such organisms would have found just as conducive a setting, and one that the scientists now think could have lasted for many millions of years.

"For all of us geologists who are very familiar with what the early Earth must have been like, what we see in Gale really doesn't look much different," Curiosity chief scientist Prof John Grotzinger told BBC News.

John Grotzinger: “We’ve reached a turning point in the mission”

He was speaking here in San Francisco at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, external, the largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary researchers.

His team is providing the conference with a status update on the rover, while simultaneously publishing six scholarly papers online in the journal Science.

Some of what is described in these papers, we have heard before. But there is now additional detail that should lend credibility to the earlier claims.

Clay clues

Ken Farley: “The dating tells us something about organic preservation”

Most of the discussion centres on a six-month investigation of a shallow depression in the crater floor close to the robot's August 2012 landing site.

Known as Yellowknife bay, this topographic low has been shown through the drilling and chemical analysis of rock samples to contain ancient mudstones.

Today, they are cold, dry and dusty, but their sediments were originally laid down in water that flowed in streams and eventually pooled into a lake.

It is clear the conditions at the time of deposition would have been more than suitable for a wide range of microbial lifeforms.

Curiosity's drill can cut down through about 5cm of rock

The scientists can tell that water - the "lubricant" of life - was significant and persistent in Gale, and that it must have been broadly neutral in pH, and not at all briney.

Much of this is evident from the presence of clay minerals, which tend to form only under particular conditions.

"I think what's very important here is that we've now made the case that these clay minerals were formed in situ," said Prof Grotzinger.

"They were not detrital; they were not blown in. They are representative of the aqueous environment that is suggested by the [look of the rocks], and that environment would have been a habitable one."

Sheepbed represents a lake that in this impression stretches some 50km across the floor of Gale Crater

Key to this habitability is the availability of essential elements, such as carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulphur, nitrogen and phosphorous. Curiosity has found them all to be present, and in a form that microbes could have accessed.

The robot also detects minerals and compounds in various states of oxidation, which organisms could have exploited in simple reactions to obtain the energy needed to drive metabolism.

The depression where Curiosity found the mudstones is only about 60m across, but the geologists on the science team believe this is just one small exposed area, and that the rock member (it has been dubbed "Sheepbed") may extend up to 30 square km or more, hidden beneath other sediments.

The thickness of the mudstone layer also hints at the length of time the water might have been present.

Curiosity scientists estimate this to be perhaps hundreds to thousands of years, just based on the visible Sheepbed layers. When the other rocks lying on top of the mudstones are taken into account - rocks that unmistakably also have been touched by water at some point - it is entirely plausible the wet environments in Gale persisted from millions to tens of millions of years.

"Even if a surface lake dries up temporarily, there should still be groundwater in the shallow subsurface," said Prof Grotzinger. "And because we're advocating chemolithoautotrophy and not photoautotrophy, those chemolithoautotrophs should be just fine down in the groundwater, and when the lake comes back again they just rise up to the surface and carry on."

Rocks sitting on top of the Sheepbed mudstones show the unmistakable action of water also

And there are some tighter constraints now on when in Mars' history these benign conditions existed, because Curiosity has been able to date the mudstones by measuring the ratio of radioactive potassium and argon atoms found within them. The result is 4.21 billion years (plus or minus 350 million years).

"It's been a dream to do radiometric dating on Mars," said Curiosity participating scientist Prof Ken Farley. "Prior to these measurements, the only way you could determine time was by counting impact craters, using a model derived from Earth's Moon where rocks have actually been dated. The model is then scaled to Mars, but it is quite uncertain," he told BBC News.

Care has to be taken in interpreting the Curiosity result, however. It refers to the age of the source minerals in the sediments washed into the lake and not the actual time of the mudstones' deposition. This would probably have been several hundred million years later.

A different technique also reveals when erosion exposed the mudstone surface seen on the planet today. This was about 78 million years ago (give or take 30 million years) - very recent, geologically speaking.

The result is significant because it will guide the strategy on where Curiosity should drill in future to find organic (carbon-rich) molecules.

Their detection is a goal of the mission, but they are easily degraded in Mars' harsh radiation environment.

The dating work, however, tells the science team to look for locations that are very freshly eroded, even more recently than the Sheepbed drilling points. Organics could very well survive in such places just a few centimetres below the surface.

Organic molecules are important because they bear down further on the habitability question. All life as we know it trades on complex carbon chemistry.

Curiosity is currently driving towards the foothills of the mountain at the centre of the crater

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published9 December 2013

- Published26 September 2013

- Published19 September 2013

- Published6 August 2013

- Published10 July 2013

- Published31 May 2013

- Published30 May 2013

- Published8 May 2013

- Published8 April 2013