Age of stars is pinned to their spin

- Published

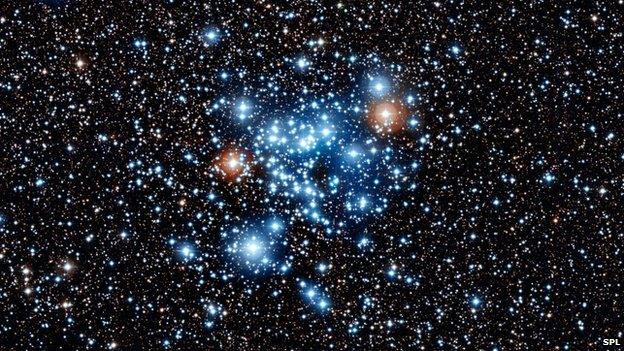

The researchers studied a cluster of stars with a known age

Astronomers have proved that they can accurately tell the age of a star from how fast it is spinning.

We know that stars slow down over time, but until recently there was little data to support exact calculations.

For the first time, a US team has now measured the spin speed of stars that are more than one billion years old - and it matches what they predicted.

The finding resolves a long-standing challenge, allowing astronomers to estimate a star's age to within 10%.

The work was presented in Seattle at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, external and also appears in the journal Nature, external.

Closing a gap

Establishing the age of stars is a central question in astronomy - much like dating fossils is crucial to studying evolution.

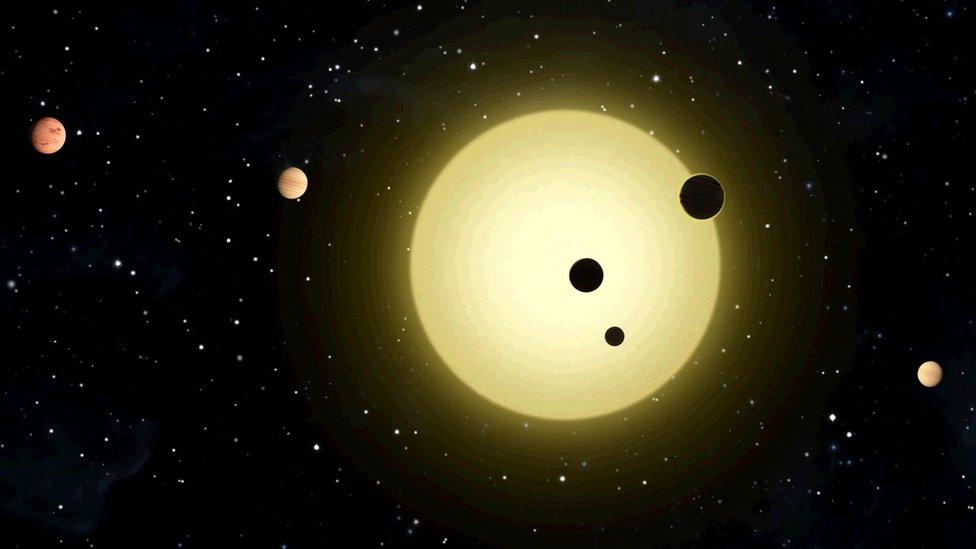

This method applies to "cool stars" - suns about the size of our own, or smaller. These are the most common stars in our galaxy and they also last for a long time.

"They act as lamp posts, lighting up even the oldest parts of our galaxy," said senior author Dr Soren Meibom from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Cool stars also host the vast majority of earth-like planets that we have spotted in the distance.

Most properties of a star like ours - like its size, mass, brightness and temperature - stay about the same throughout most of its life.

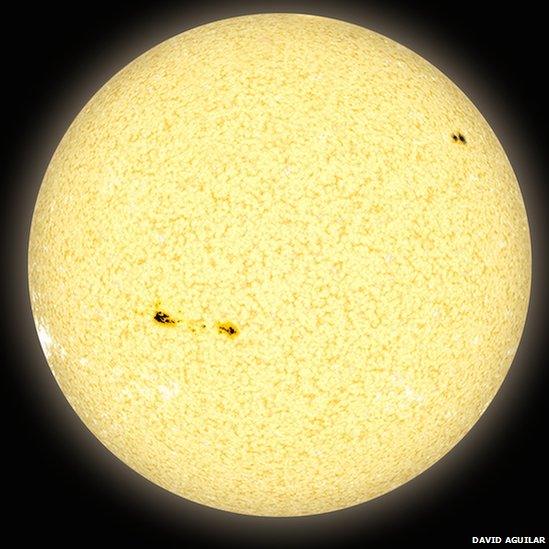

It is relatively easy to tell the age of young stars because they have large sunspots

This makes figuring out a star's age decidedly tricky.

The solution of measuring spin was first proposed in the 1970s and was dubbed "gyrochronology", external in 2003.

"A cool star spins very fast when it's young, but just like a top on a table it gets slower and slower as the star grows older," Dr Meibom said.

But it is difficult to see a star spinning. Astronomers use sun spots, travelling across the surface, and these only dim its brightness by much less than 1%.

Old stars are particularly problematic, because they have fewer and smaller spots.

Dr Meibom's team used images from the very sensitive Kepler space telescope, which has been trailing Earth around the Sun since 2009.

They managed to measure spin speeds for 30 stars in a specific cluster known to be 2.5 billion years old.

This cluster, known as NGC 6819, plugs what Dr Meibom called a "four-billion-year gap" in our knowledge of stellar spin.

Half-built clock

Before the Kepler mission, we only had data from very cool stars in very young clusters, all less than 0.6 billion years old and all spinning fairly fast (about once a week).

In 2011, Dr Meibom's team used Kepler images to report on a different cluster, the one-billion-year-old NGC 6811. Its cool stars spin about once every 10 days.

But beyond that, the only star we knew both age and spin rate for was our own sun - 4.6 billion years old, with a spin period of 26 days.

"The construction of the cool star clock was on hold," Dr Meibom said.

Now, the clock is looking good. The sun-like stars in the freshly studied cluster sit squarely and satisfyingly in the gap, spinning about every 18 days.

Older stars, more like our own Sun, are trickier to assess because they have fewer and smaller spots

"These new data show, with real observations, that this is on solid ground," Dr Meibom told BBC News.

"We can get age as accurately as about 10% from this method."

He added that this is a big improvement on some other methods for guessing stars' age, where the margin of error for cool stars can reach 100%.

Ruth Angus, a PhD student researching gyrochronology at the University of Oxford, said the results were "a really big deal" for the field.

"More evidence has been slowly accumulating that lots of stars do seem to follow this pattern, but how reliably stars fall onto this relation is a bit of an unknown," Ms Angus told the BBC.

"This cluster will certainly help with our understanding of how good gyrochronology is as a method, and how valid it is.

"It shows that these stars are doing what they're expected to do, and everything's peachy."

- Published26 February 2014

- Published2 June 2014

- Published20 February 2011