Bloodhound Diary: Art meets science

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will mount an assault on the world land speed record. Bloodhound will be run on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2015 and 2016.

Wing Commander Andy Green, the current world land-speed record holder, is writing a diary for BBC News about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

2014 has been the most remarkable year yet for Bloodhound.

I've just looked back at my January diary for 2014, external, which shows the bare framework of the upper-chassis and talks about Nammo as our "new rocket partner".

Less than 12 months later, the upper-chassis is finished, our Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine has been test-fitted, we're building up the car's suspension, Nammo has completed four test firings of our hybrid rocket - the list goes on.

We've also added to our list of world-class partner companies, with Castrol supplying all our high-performance lubricants and Jaguar joining the project as our Innovation Partner.

The Bloodhound engineering team had 10 distinct goals (relating to 10 different areas of the car) to achieve by the end of 2014.

We've hit all 10, which leaves us on track to roll the car out in summer 2015 for its first test runs.

If you haven't seen the Popular Mechanics view of how we've got to this point, then read it here, external - it's a good article with some unique graphics.

Perhaps the single biggest job for 2014 was completing the upper-chassis.

After lining up, drilling off and riveting 12,000 holes, the bonding agent (glue) between the titanium panels and the aluminium ribs needs to be cured (cooked) to make it set hard.

Into the autoclave, fingers crossed...

The curing temperature is 175C, and that's where the problems start.

Aluminium and titanium expand at different rates when they heat up.

The coefficient of linear expansion is a measure of how much: for aluminium it's about 22 (x10^-6m/mK, but don't worry too much about the units). For titanium it's about 9.

That means that if you heat a 1-metre-long piece of aluminium up to 175C, it will grow by about 3.5mm.

A 1-metre-long piece of titanium will only grow by 1.4mm.

If the two metals are joined together when you heat them up, then the combination will bend, a lot.

Checking the results...

This can be a good thing - your house is probably full of bimetallic strips that use this effect. In central heating thermostats, when the house cools down the strip bends and switches the heat on. In electrical circuit breakers, if the current is too high, the strip gets hot and bends, turning the power off.

The problem comes when you heat up a precision-made supersonic chassis to 175C, with the different metals trying to grow at different rates.

If we bend the chassis, it's wrecked, and any chance of running Bloodhound in 2015 has gone.

After over a year of work to get to this point, the chassis cure was the last critical step. We put the chassis, mounted on its Manufax jig, into the huge autoclave (oven) at the National Composites Centre down the road from us in Bristol.

Heating it up to 175C and cooling it down again was done very slowly, over a period of eight hours.

The result? A near-perfect shape, with just a tiny amount of 'pillowing' (panel distortion) in a couple of places. A huge sigh of relief and we're one step closer to our 2015 roll-out.

Just about perfect!

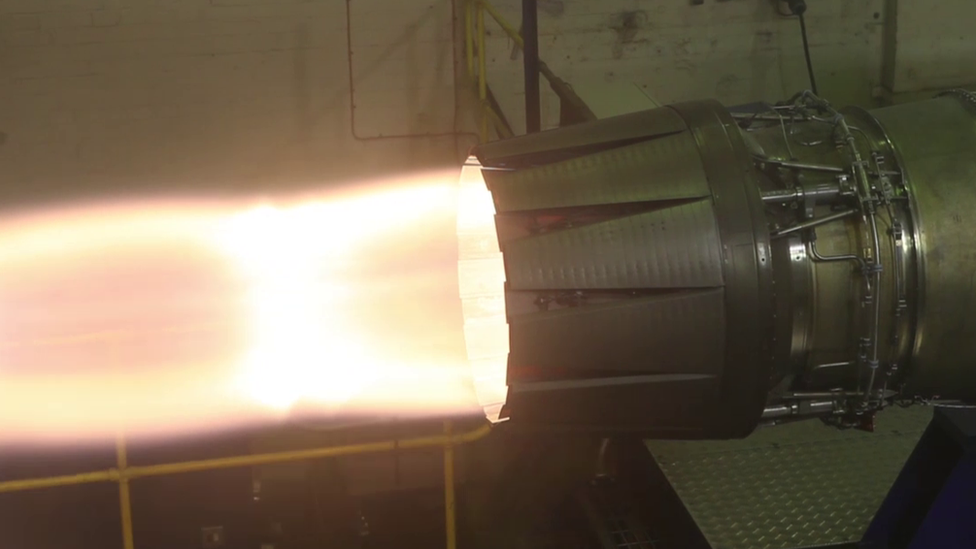

I was lucky enough to get out to Norway last month, to see the latest hybrid rocket firing at Nammo's test range.

Nammo is developing a prototype rocket which will one day power the next generation of satellite launchers.

Meanwhile, the safety benefits of hybrid technology means that it's perfect for Bloodhound.

As a result, if you'll forgive the pun, we're the "launch customer" for Nammo's new rocket.

The impressive thing about watching the Nammo test was just how measured and controlled everything was.

For a prototype rocket test, they made it look easy.

Norwegian hybrid power. One of the Nammo rocket tests

The results were equally impressive, with a steady 28-29kN (just under 3 tonnes) of thrust for the duration of the firing.

Watch the video of the test firing here, external - my favourite bit is when the camera on the other side of the lake gets blown over. This rocket's got some punch.

In February 2015, we're going to test the rocket with Bloodhound SSC's pump system, using the 550 hp V8 Jaguar engine.

With the increased pressure from the Bloodhound system, we're hoping to deliver a much higher thrust from the rocket.

Impellor: Art meets science

For 2015, the exact rocket thrust is not that critical, as we're "only" aiming to reach 800mph to test Bloodhound.

However, for 2016, the requirement is more demanding.

To reach 1000mph, we will need about 12 tonnes (120 kN) of thrust.

If we can increase the power output to 40kN for a single rocket, then we only need to fit three of them in the car (instead of four), which makes the rocket system packaging a lot simpler. We'll find out in a couple of months.

One of the technology advances that let us move from our previous F1 engine (750hp) to the more reliable Jaguar V8 (550hp) is a more efficient pump for the HTP (high test peroxide) oxidiser.

This pump needs to deliver 800 litres of HTP at 76 Bar (1000 psi) in just 20 seconds, which is why it needs so much power to turn it.

A newly designed impeller (the spinning bit inside the pump) has given us probably the most efficient rocket pump in history.

More efficiency = less power needed, so the Jaguar V8 is perfect for the new pump.

Next step, fit the wheels

The rocket system is where space technology meets motor racing, and where engineering meets art. The new impeller is a thing of sheer beauty.

The rest of the car is coming on just as well. The jig has been set up ready for the fin build and Jaguar is living up to its name as our Innovation Partner, by supplying the front bulkhead, one of many bits of Jaguar-made hardware going into Bloodhound.

Most of the front end of the car has now been delivered, so we'll shortly be turning the cockpit section round on the steel surface table, so that we can build up the front end for the first time.

Ever since Bloodhound started, we've been talking about the car and making brilliant bits of technology for it.

As the driver, I don't yet have a "feel" for Bloodhound as a land vehicle, perhaps because it still looks like the fuselage of a supersonic jet-fighter-space plane.

Quite simply, it hasn't got any wheels, so it doesn't look like a "car" to me yet.

This is about to change. We've been building up the front and rear suspension assemblies this past month and it won't be long before Bloodhound SSC is sitting on its wheels, looking and feeling like a car. Roll on 2015.

- Published3 January 2015

- Published7 December 2014

- Published27 October 2014

- Published26 September 2014

- Published11 August 2014

- Published30 August 2014

- Published13 June 2014

- Published19 December 2013

- Published4 July 2013

- Published13 May 2013

- Published3 October 2012

- Published7 February 2011

- Published13 November 2010