Genomes reveal Darwin finches' messy family tree

- Published

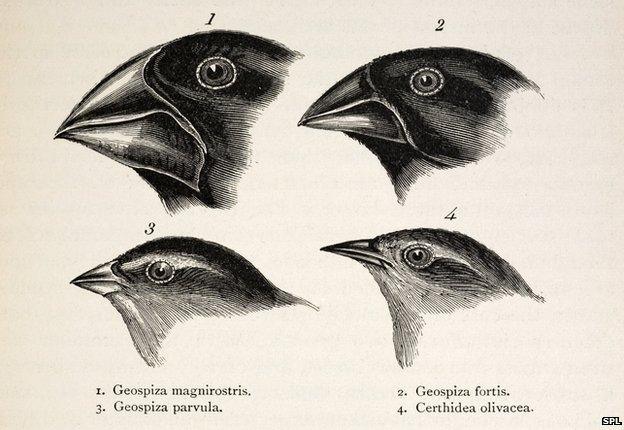

Different food sources available in the archipelago led the finches to evolve different beak shapes

The most extensive genetic study ever conducted of Darwin's finches, from the Galapagos Islands, has revealed a messy family tree with a surprising level of interbreeding between species.

It also suggests that changes in one particular gene triggered the wide variation seen in their beak shapes.

Scientists in Sweden and the US used genome sequences of 120 individual birds from 17 different species to perform their analysis.

The work appears in the journal Nature, external.

This "most singular group of finches" appeared in Charles Darwin's famous journal from the voyage of the Beagle. Darwin collected specimens which were later classified by the ornithologist John Gould, back in London.

"Darwin was amazed by the beak diversity in species that were otherwise very similar," said the new study's senior author Prof Leif Andersson, from Uppsala University in Sweden.

Only about 1.5 million years ago, these species started branching out from a common ancestor, which colonised the relatively young Galapagos archipelago - thrust from the ocean by volcanic activity.

According to Darwin's now-famous theory of natural selection, the birds rapidly adapted to the different food sources that were available in their new home, where they faced little competition from other birds. Chief among these adaptations were different beak shapes: stronger, blunter beaks for cracking tough seeds or insects, for example.

'Genetic innovation'

Prof Andersson set out to trace the genetics behind that diversity with a team of colleagues including Professors Rosemary and Peter Grant of Princeton University, who have spent 40 years studying the iconic finches.

They sequenced the genomes of multiple individuals from all 15 species of Darwin's finches, one of which inhabits the rather more distant Cocos Island, along with two related bird species that live on the South American mainland and the West Indies.

The medium ground finch has previously displayed surprisingly rapid beak changes in response to drought

One of the things that the team looked for, after a detailed comparison of 120 individual genomes, was genetic changes that could explain the diversity of beak shapes.

They did a particular comparison of two pointed-beak species and two blunt-beak species. Differences in one specific gene, called ALX1, were associated not only with beak differences between species, but also differences within one species: the medium ground finch, which has previously shown rapid beak changes in response to drought.

"What we discovered is basically two variants of ALX1," Prof Andersson explained.

"One is associated with pointed beaks - that is the ancestral form. Then there is a variant associated with the blunt beaks. That's the derived form.

"The blunt beak version is a genetic innovation that occurred on the islands."

However, he emphasised that this does not mean ALX1 - a gene also linked to facial defects in humans - controls beak shape on its own.

"There are multiple genes that contribute. But we think that ALX1 is one of the most important, if not the most important factor that has changed on the island."

Messy history

The study also revealed a surprisingly large amount of "gene flow" between the branches of the family.

This indicates that the species have continued to interbreed or hybridise, after diversifying when they first arrived on the islands.

Charles Darwin first described the different finches on his landmark voyage aboard the Beagle

Normally when two species start to develop independently, they reach a point where there are so many genetic differences that animals from the different lineages no longer mate, or their hybrid offspring are sterile - as is the case when a horse and a donkey produce a mule.

"It's been observed that the species of Darwin's finches sometimes hybridise - Peter and Rosemary Grant have seen that during their fieldwork," Prof Andersson told the BBC.

"But it's difficult to say what the long-term evolutionary significance of that is. What does it contribute?"

In fact, the team's findings suggest that hybridisation is very important to these birds' evolution. In particular, they saw that the rise and fall of pointed beaks in one species - once again, the medium ground finch - was driven by hybridisation with a different, pointed-beak species.

Rosemary and Peter Grant, two of the study's authors, have been studying Darwin's finches since the 1970s

"This is a very exciting discovery for us," Prof Rosemary Grant said. "We have previously shown that beak shape in the medium ground finch has undergone a rapid evolution in response to environmental changes. Now we know that hybridization mixes the different variants of an important gene, ALX1."

Other geneticists have expressed mixed reactions to the results. Dr Julia Day, from University College London, was impressed by the level of mixing reported between the finch species - which she said are "a textbook example of radiation".

She told the BBC: "The fact that they're finding this hybridisation going on - this genetic mixing - it's quite a seminal finding.

"When you look at their results, you can see the trees are quite messy, in terms of the traditional species groupings."

Prof Peter Keightley from the University of Edinburgh, though largely convinced by the results, was less surprised that the finches had interbred so extensively.

"These islands are pretty close together. So it's not surprising that they are flying from one island to the other," he said.

Some of the traditional species might not, in fact, be genuinely distinct, he added.

Meanwhile Prof Andersson and his colleagues, despite having shown convincingly that the finches' family history is decidedly blurry, actually argue for the addition of three new species to the existing tally of 15.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published5 February 2015

- Published28 October 2014

- Published1 January 2014