'Gerbils replace rats' as main cause of Black Death

- Published

The much-maligned black rat may not have caused repeated outbreaks of the plague

Black rats may not have been to blame for numerous outbreaks of the bubonic plague across Europe, a study suggests.

Scientists believe repeat epidemics of the Black Death, which arrived in Europe in the mid-14th Century, instead trace back to gerbils from Asia.

Prof Nils Christian Stenseth, from the University of Oslo, said: "If we're right, we'll have to rewrite that part of history."

The study is in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external.

The Black Death, which originated in Asia, arrived in Europe in 1347 and caused one of the deadliest outbreaks in human history.

Over the next 400 years, epidemics broke out again and again, killing millions of people.

It had been thought that black rats were responsible for allowing the plague to establish in Europe, with new outbreaks occurring when fleas jumped from infected rodents to humans.

Rat reservoir

However, Prof Stenseth and his colleagues do not think a rat reservoir was to blame.

They compared tree-ring records from Europe with 7,711 historical plague outbreaks to see if the weather conditions would have been optimum for a rat-driven outbreak.

He said: "For this, you would need warm summers, with not too much precipitation. Dry but not too dry.

"And we have looked at the broad spectrum of climatic indices, and there is no relationship between the appearance of plague and the weather."

When the weather is favourable, Asia's giant gerbils thrive, increasing the chance of plague transmission

Instead, the team believes that specific weather conditions in Asia may have caused another plague-carrying rodent - the giant gerbil - to thrive.

And this then later led to epidemics in Europe.

"We show that wherever there were good conditions for gerbils and fleas in central Asia, some years later the bacteria shows up in harbour cities in Europe and then spreads across the continent," Prof Stenseth said.

He said that a wet spring followed by a warm summer would cause gerbil numbers to boom.

"Such conditions are good for gerbils. It means a high gerbil population across huge areas and that is good for the plague," he added.

The fleas, which also do well in these conditions, would then jump to domestic animals or to humans.

And because this was a period when trade between the East and West was at a peak, the plague was most likely brought to Europe along the silk road, Prof Stenseth explained.

'Perfect storm'

"To me this was rather surprising," he said.

"Suddenly we could sort out a problem. Why did we have these waves of plagues in Europe?

"We originally thought it was due to rats and climatic changes in Europe, but now we know it goes back to Central Asia."

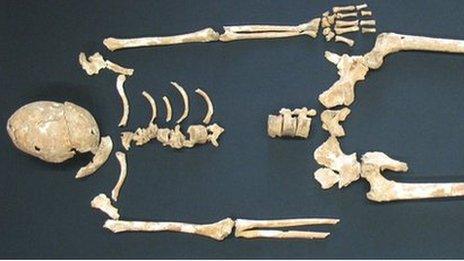

The team now plans to analyse plague bacteria DNA taken from ancient skeletons across Europe.

If the genetic material shows a large amount of variation, it would suggest the team's theory is correct.

Different waves of the plague coming from Asia would show more differences than a strain that emerged from a rat reservoir.

The plague died out in Europe after the 19th Century, however outbreaks continue to this day in other parts of the world.

The World Health Organization said there were nearly 800 cases reported worldwide in 2013, including 126 deaths.

In another paper, published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, researchers in the US said that the expansion of agriculture was placing East Africa at an increased risk of the plague.

As cropland increased, rodent populations were also rising, creating "the perfect storm for plague transmission", the researchers said.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published30 March 2014

- Published8 May 2014

- Published10 October 2013

- Published28 January 2014