Mercury has been 'dynamic world'

- Published

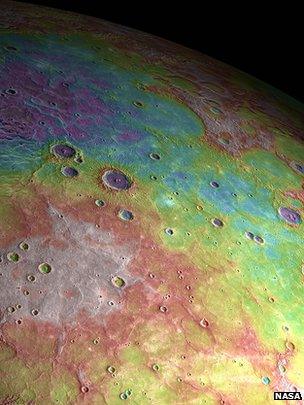

A broader view: Some areas (white) have clearly been deformed and risen over time

The planet Mercury was once an active and dynamic planet, according to new evidence from a Nasa spacecraft.

Data from the American Messenger probe shows that impact craters on the planet's surface were distorted by some geological process after they formed.

The findings, reported in Science magazine, challenge long-held views about the closest world to the Sun.

Another study looking at Mercury's gravity field shows that the planet has an unusual internal structure.

As well as being published in the journal Science, the research has also been presented here at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

"Many scientists believed that Mercury was much like the Moon - that it cooled off very early in Solar System history, and has been a dead planet throughout most of its evolution," said Maria Zuber, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

"Now, we're finding compelling evidence for unusual dynamics within the planet, indicating that Mercury was apparently active for a long time."

Dr Zuber and her colleagues used laser measurements from Messenger to map out a large number of impact craters, and found that many had tilted over time.

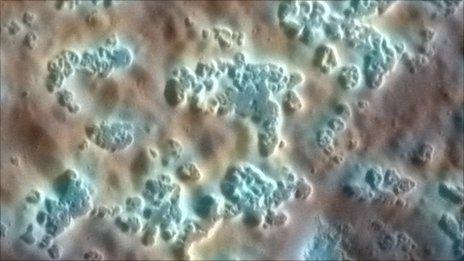

This suggests that geological processes within the planet have re-shaped Mercury's terrain after the craters were created.

Observations of Caloris Basin, the planet's largest impact feature, show that portions of the crater floor stand higher than its rim, suggesting that forces within Mercury's interior pushed the surface up after the initial collision event.

The researchers also identified an area of lowlands near Mercury's north pole that could have migrated there over the course of the planet's evolution. A process called polar wander can cause geological features to shift around on a planet's surface.

In theory, the process of convection going on within the mantle could drive such changes. But Dr Zuber said this would be unusual in Mercury's case, because the mantle is so thin.

Another potential explanation could be that features on the surface were distorted as the planet's interior cooled and contracted. This fits in with observations that some surface features on Mercury have been exposed to high levels of stress.

Scientists had long known that the planet possessed a large, iron-rich core and relatively thin outer shell.

Several theories had been put forward to explain this, including the idea that Mercury was struck early in its history by a large space rock, stripping away much of the original crust and mantle.

Messenger's measurements of the planet's gravity field have now confirmed an exceptionally large iron core which is partially liquid.

This core makes up about 85% of the planet's radius, with the outer shell occupying about 15% - about as thin as the peel on an orange. But this thin outer shell is also surprisingly dense.

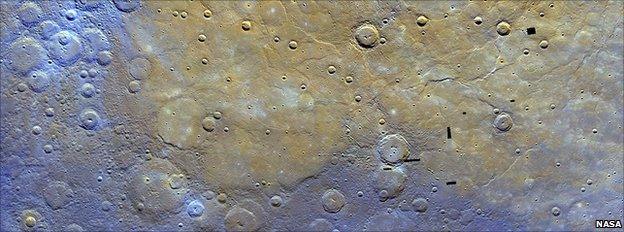

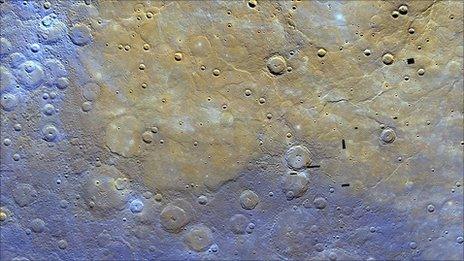

An enhanced colour view shows the smoother northern volcanic plains on Mercury to have a different composition (yellow) to the surrounding material

In order to explain this, Dave Smith, from Nasa's Goddard Space Flight Center, and colleagues propose that the core is surrounded by a solid layer of iron sulphide - a type of structure not known to exist on any other planet.

The iron sulphide layer is in turn encased by a thin mantle and crust made from silicate rock.

"We had an idea of the internal structure of Mercury, [but] the initial observations did not fit the theory so we doubted [them]," said Dr Smith.

"We did more work and concluded the observations were correct, and then reworked the theory... it's a nice result."

Mercury Messenger is the first ever mission to orbit the first planet from the Sun. Messenger took up that position in March 2011, and has since circled the planet twice a day, collecting nearly 100,000 images and more than four million measurements of the surface.

Throughout its mission, the spacecraft has had to contend with tidal forces from the Sun, which have tugged the probe out of its preferred orbit, as well as "sunlight pressure" in which photons, or packets of light, from our star "press" on the spacecraft.

The team has periodically had to adjust the probe's orbit and apply corrections to its measurements to account for the Sun's effects.

Paul.Rincon-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter, external

- Published30 September 2011

- Published16 June 2011

- Published18 March 2011

- Published15 July 2010