LHC restart: Short circuit slows preparations

- Published

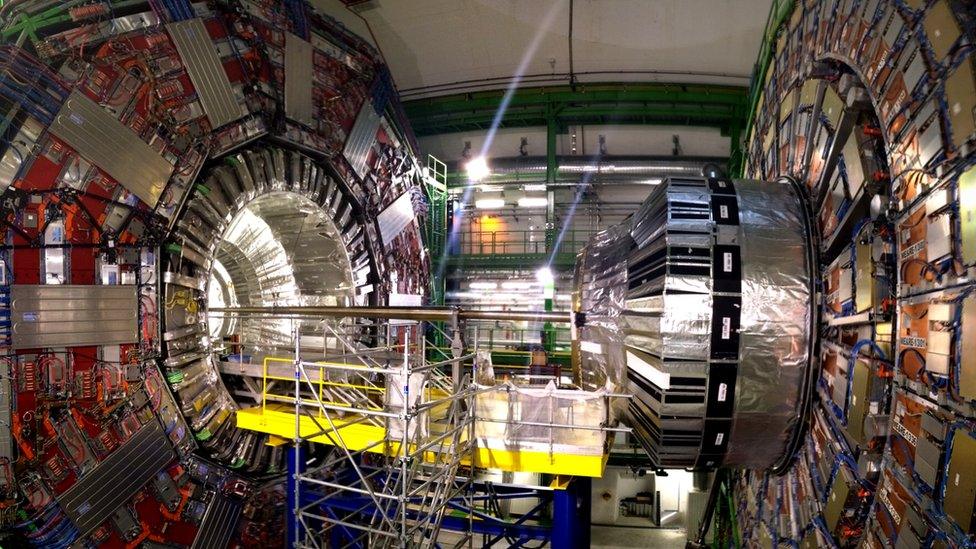

Teams on the collider's big experiments like Atlas (pictured) are using the time to make extra tweaks

The rebooted Large Hadron Collider is facing a delay of days or even weeks, after a short circuit was detected in one of its powerful electromagnets.

Following a two-year break, the LHC is getting ready to smash protons together once again - at new, higher energies.

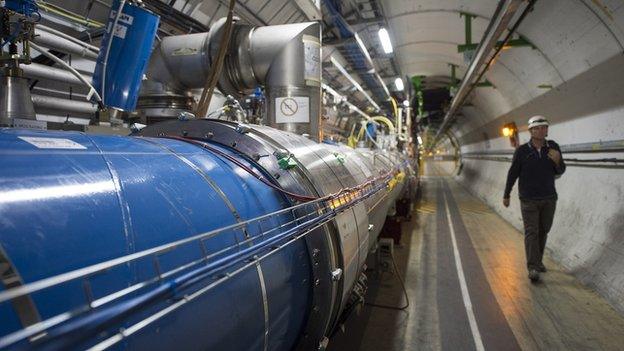

Before the collisions begin, proton beams must travel safely around its 27km circumference in both directions.

Those full laps were expected to begin this week, but that plan will now be revised.

Cern, the European nuclear research organisation which runs the LHC, said the "intermittent short circuit" was discovered on Saturday.

It affected one of the magnets that will eventually send protons racing around the LHC - specifically a magnet in "sector 3-4".

Nearby, sector 4-5 of the machine - the area which triggered a more eventful false start, external when the LHC first commenced operations in 2008 - had already been lagging behind the other seven in the gradual "training" process that the magnets must go through.

But the short circuit is a more serious problem, in terms of the delay it could impose on the restart.

Cern said it was "a well understood issue", but because the magnets are supercooled to temperatures approaching absolute zero (-273C), the repair could be time-consuming.

If it requires the faulty magnet to be warmed up and re-cooled, the delay may stretch from a few days to "several weeks", the organisation announced on Tuesday, external.

"Any cryogenic machine is a time amplifier, so what would have taken hours in a warm machine could end up taking us weeks," said Cern's director for accelerators, Frederick Bordry.

'No time wasted'

Scientists at Cern emphasised that the restart timetable was always flexible and that Run Two of the world's largest machine is still on target.

Rolf Heuer, the organisation's director general, said: "All the signs are good for a great Run Two. In the grand scheme of things, a few weeks' delay in humankind's quest to understand our Universe is little more than the blink of an eye."

When it eventually comes to the science, there are many big items on the LHC team's wish list for Run Two - including detecting dark matter, making further observations of the Higgs boson, and ultimately, the search for a "new physics" outside of the Standard Model.

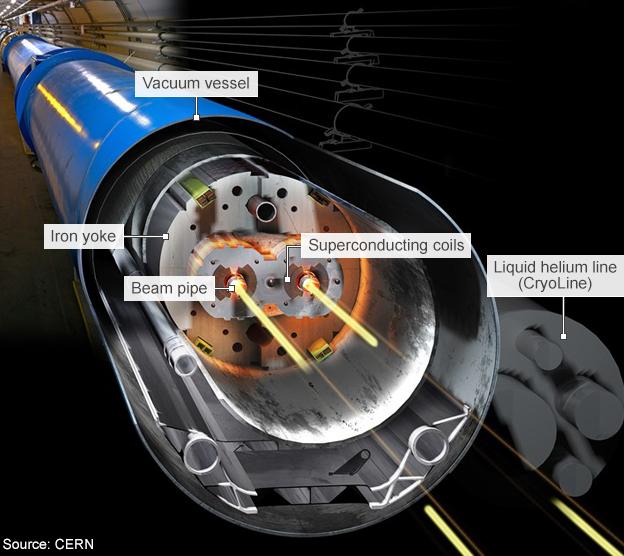

Two parallel pipes carry the beams in a 27km circle at fractionally less than the speed of light

Particle physicist Jonathan Butterworth, from University College London, works on Atlas - one of four major experiments spaced around the LHC's huge circle. He told BBC News that the experiment teams were ready to go, and waiting to hear more from the scientists and engineers who manage the beams.

"It's a very separate organisation, basically," Prof Butterworth said. "The accelerator guys are all within Cern - and we're sort of ready and waiting. We do what they tell us at this stage."

But he added that the time will not be wasted. The experiment teams can make extra improvements to their own systems while they wait - particularly to the computer code used to control the detectors and analyse data.

"Every day, we have people frantically coding stuff up to be even more ready," he said.

Muon practice

Dr Andre David, who works for Cern on the CMS experiment, also said the additional time would be valuable. He and his colleagues are "enjoying" the chance to make sub-millimetre adjustments to some of the detectors inside CMS.

"We are profiting from this time to collect more cosmic ray data, which is crucial to align the very tiny inner detectors," Dr David told the BBC.

Cosmic rays are particles from outer space that bombard the Earth, but few of them penetrate the atmosphere. High-energy muons, however, interact so infrequently with matter that some of them make it right into the LHC tunnels, 30 storeys underground.

The proton beams are steered by magnets which must be "trained" with gradually increasing current

"As they go through the experiment, we can detect them, just like any other muon produced in a collision," Dr David said. "These muons are extremely valuable, because we can figure out where the signals are that they leave behind - without any beams."

By making miniscule adjustments to the alignment of their detectors, the researchers can "smooth out" the way they will identify and measure these particles when they fall out as debris from proton collisions.

Those collisions were originally - tentatively - timetabled to kick off in May, but the short circuit now makes that estimate seem even less certain.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published16 March 2015

- Published5 March 2015

- Published15 February 2015

- Published10 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014