'Lost' sea turtles don't go with the flow

- Published

Turtles in the study were less than two years old; they can take 10-20 years to reach sexual maturity

A tracking study has shown that young sea turtles make a concerted effort to swim in particular directions, instead of drifting with ocean currents.

Baby turtles disappear at sea for up to a decade and it was once assumed that they spent these "lost years" drifting.

US researchers used satellite tags to track 44 wild, yearling turtles in the Gulf of Mexico and compared their movement with that of floating buoys.

They reported their findings in the journal Current Biology, external.

"This is the first study to release drifters with small, wild-caught yearling or neonate sea turtles in order to directly test the 'passive drifter' hypothesis in these young turtles," said the paper's senior author Dr Kate Mansfield, who runs the turtle research group at the University of Central Florida.

She and her team want to improve our understanding of these animals' behaviour and their whereabouts at sea, in order to help protect them.

There are seven species of sea turtle and all of them are endangered or threatened.

Wrong turtles?

To test the idea that they spend their juvenile years drifting around at the mercy of the current, Dr Mansfield and her colleague Nathan Putman set about catching wild turtles and attaching specially-designed, solar-powered tags.

This is easier said than done, Dr Putman told BBC News.

"They're not called the lost years for nothing," he said. "These turtles are tough to catch."

Turtles spend a lot of time in floating beds of seaweed, but the study revealed concerted swimming efforts

Sometimes a voyage of 100km or more off-shore yielded none of the animals at all; at other times the research team struck it lucky.

"Some trips there'd be a patch of them - 10 little turtles all together. But it took a while to get the sample size that was needed," said Dr Putman, from the Southeast Fisheries Science Center run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Even when they did find turtles, many of them were the wrong turtles - or so the team thought. They were expecting to see the critically endangered Kemp's ridley turtle, which is known to nest on beaches in the gulf.

But in fact it was easier to find green sea turtles, whose closest major nesting beach is some 1,000 miles (1,700km) south, in Costa Rica.

"In the first year and a half we didn't even tag any of the green turtles, because we thought maybe this is a fluke - we won't get a big enough sample size of these guys," Dr Putman said.

"But in fact they were much, much more abundant - so we got the permits changed in order to see what these green turtles were doing."

44 turtles were tagged with solar-powered tracking devices

In the end the study tracked 20 Kemp's ridley turtles and 24 green turtles, all between six months and two years of age. Each time the team tagged one or more turtles, they released them alongside two buoys or "drifters" with their own satellite tags.

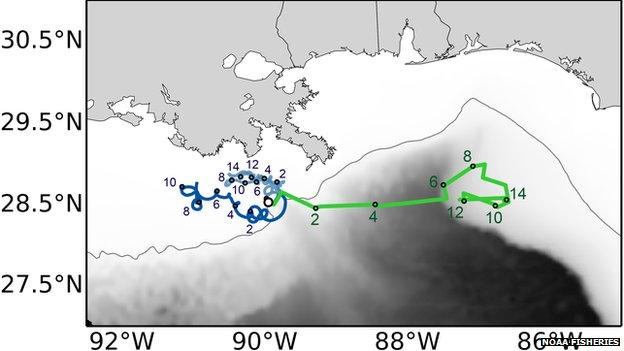

This allowed them to watch the separation between the drifting buoys and compare it to the movement of the turtles.

"We wanted to see - what is the divergence you'd expect based purely on ocean circulation processes, compared to the difference you'd see based on that plus swimming behaviour," Dr Putman explained.

"The biggest surprise was, when you look at the tracks, they go completely different places. Drifters and turtles diverge quickly and have very different movement properties."

This indicates that the little turtles are surprisingly active swimmers.

'Very directed'

Based on ocean current models, the team also calculated the turtles' actual swimming speed, relative to the water around them. They are not about to break any records: typical estimated speeds were just a few centimetres per second.

But their persistence was impressive, Dr Putman said.

"The turtles were very directed in their swimming, whereas the drifters were not. That was the huge difference.

"The green turtles, for instance, were really set on going east a lot of the time. And the Kemp's ridley turtles, over large portions of the tracked area... were very convinced that they should be swimming north."

Free-floating "drifters" were compared to the movement of the toddler turtles

Dr Rebecca Scott, who studies sea turtle spatial ecology at Geomar Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, commented that this was an "important study".

She told the BBC it offered "new key evidence to support our growing realisation that juvenile turtles do not simply just drift with ocean currents".

Improvements in tracking technology are beginning to fill in these animals' "lost years", added Dr Scott, who has previously tracked hatchlings from the beach using acoustic pingers.

"However, since satellite tags are still too large to attach to tiny hatchling turtles, a big challenge... remains to assess how the relative contributions of ocean current driven dispersal and active swimming develop during the first few critical months of their life."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

This map shows one turtle's path (green) relative to drifting buoys (blue)

- Published23 October 2014

- Published21 July 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published5 March 2014