Vast replica recreates prehistoric Chauvet cave

- Published

BBC Newsnight was given rare access to the Chauvet cave and its remarkable art

In the Ardeche gorge in southern France lies one of the most important prehistoric sites ever discovered.

It's locked away behind a thick metal door, hidden halfway up a towering limestone cliff-face.

Few people have ever been allowed inside, but BBC Newsnight has been granted rare access by the French Ministry of Culture and Communication.

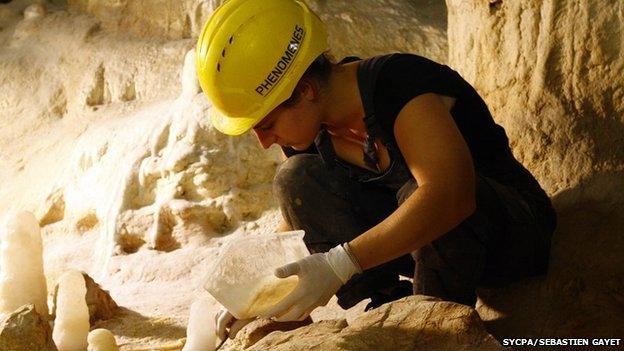

We slide through a metal passageway on our backsides, and then tentatively descend a ladder.

It takes a few moments to adjust to the darkness, but our head torches soon reveal that we've entered into a vast cave system of geological beauty.

We weave along the narrow metal walkways; stalactites and stalagmites glimmer in the light, sparkling curtains of calcite hang down from above and the floor is awash with the bones of long-dead animals.

The caverns are spectacular, home to stalagmites and stalactites that have formed over thousands of years

Until recently, the last people to set eyes on this place were our Palaeolithic ancestors, before a rock fall cut it off from the outside world.

This exquisitely preserved time-capsule was sealed shut for more than 20,000 years, until it was discovered by three cavers - Eliette Brunel-Deschamps, Christian Hillaire and Jean-Marie Chauvet, after whom it is now named - on the 18th December 1994.

At first they thought they had uncovered a network of spectacular caverns.

But as they ventured deeper inside, they realised this was the discovery of a lifetime - the cave held some of the oldest art ever found.

It's breathtaking when we get our first glimpse of it.

The walls are adorned with hundreds of paintings.

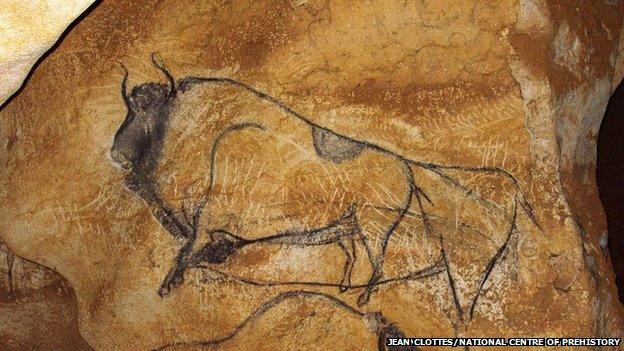

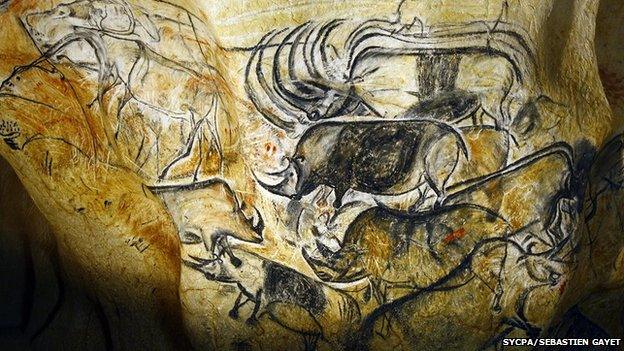

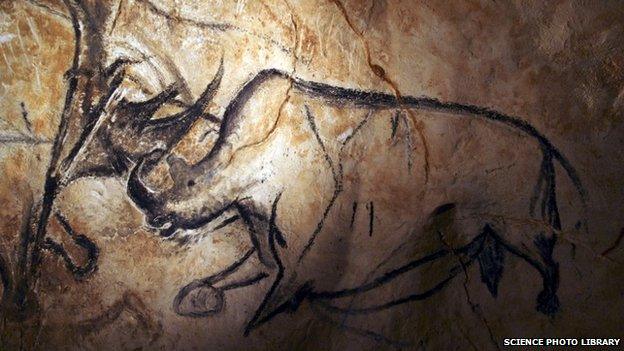

Most of them are animals - woolly rhinos, mammoths, lions and bears intermingle with horses, aurochs and ibex.

Some are isolated images: we wander past a small rhino, a single, lonely creature daubed on the rock. But there are also huge, complex compositions, a menagerie of beasts jostling for space on great swathes of the cavern wall.

Some of the compositions are complex scenes showing many different animals

The art provides a snapshot of the beasts that roamed Ice Age Europe 35,000 years ago

The artists worked with the contours of the rock to create these images

Painted in charcoal and red ochre, or etched into the limestone, careful shading and skilful technique bring the animals to life, revealing movement and depth.

"They are very sophisticated," says Marie Bardisa, the head curator at the Chauvet Cave - which is also known as the Decorated Cave of Pont d'Arc. She delights in this rare chance to show off the art.

"They used the relief of the rock to give the forms, to give the shadows, to express so many things.

"They saw the animals in the rock," she adds.

"More than 400 animals have been painted here, there are still lots of things to discover."

The paintings are so well preserved, they look as if they were drawn yesterday. But while there has been some debate over their age, the most recent radiocarbon dating suggests this work is more than 35,000 years old.

The rock drawings offer a rare glimpse into the lives of our early human ancestors and the Ice Age world they inhabited.

But few will ever have the chance to see it.

As soon as the cave was discovered, on the advice of scientists, the French authorities closed it off to visitors.

"If the public came into this cave, first of all, we risk contamination," explains Marie Bardisa.

"The temperature can grow very quickly, the balance of the climate would be disturbed so much we could have alteration of the paintings - we don't want to take this risk."

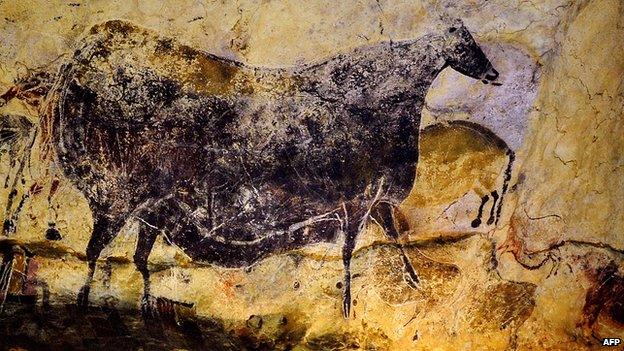

Fungi and bacteria were introduced to the Lascaux caves after they were opened to the public

Some fear the art of the Lascaux caves is damaged beyond repair

Archaeologists know this from bitter experience.

In 1940, the Lascaux cave system was discovered in southwest France.

For more than 20 years, millions of visitors flocked to see its stunning paintings, until visible damage from mould and bacteria forced the cave to be shut down.

Even today, scientists are still struggling to save the paintings, which may have been damaged beyond repair.

With the Chauvet cave, the French authorities have had to find a way to both preserve and promote this precious heritage.

This big problem required a big solution.

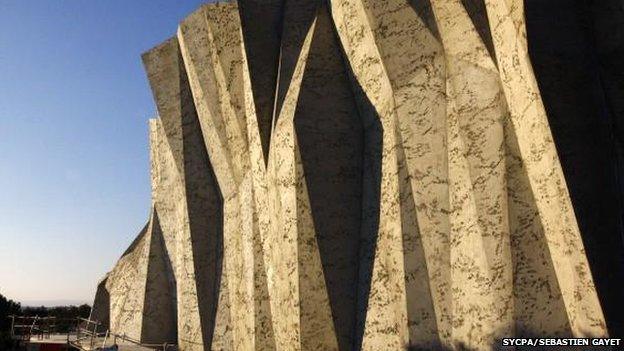

The reconstruction covers 3,500sq m and is housed in a huge concrete-clad building

It accurately replicates the most important features of the Chauvet cave

A few kilometres away, on a pine covered hill, sits a stadium-sized concrete hanger.

Inside is a recreation of some of the Chauvet cave's most important features, reproduced to scale.

It's cost 55m euros to build, has taken eight years from inception to completion and has involved hundreds of people.

Hi-tech scans, 3D-modelling and digital images of the original cave were used to create the copy.

Layered over a huge metal scaffold, the limestone walls have been reproduced in concrete, the stalagmites and stalactites have been remade in resin.

Even the temperature has been set to match that of the original.

A metal scaffold provides a framework for the illusion

The walls of the replica are made from concrete instead of resin

Finer geological features have been crafted from resin

If you ignore the hordes of visitors who have come to press day, you do get the sense of being in a real cave.

The paintings, though, are the main attraction.

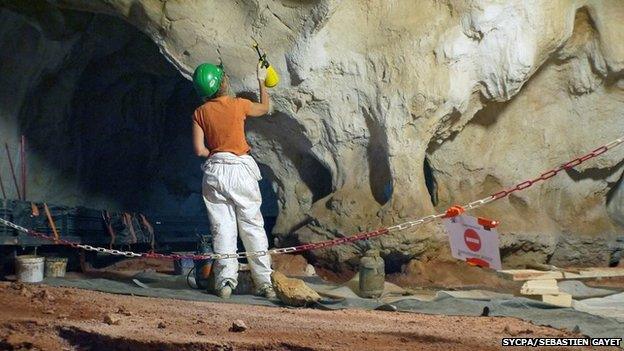

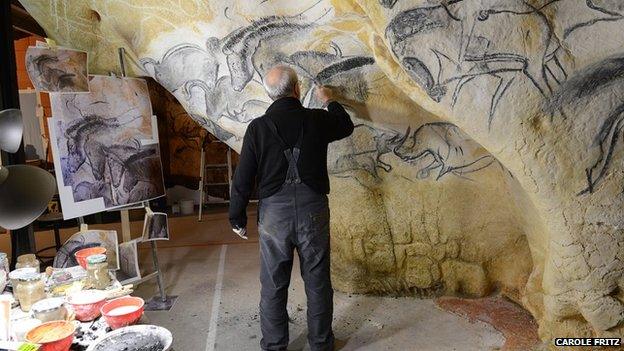

"The process is very complex. You have to be very respectful to the original," says Gilles Tosello, who spent six months reproducing some of the Chauvet cave's most impressive compositions.

The art was recreated offsite. Digital images of the paintings were projected onto canvasses of fake rock to guide the artists.

"Our raw material is resin, and it is completely different to limestone, mud and clay in the original cave," explains Mr Tosello.

"But that was part of the challenge - we are using illusions to recreate the original compositions."

Gilles Tosello spent months in his Toulouse studio recreating some of the caves most complex murals

Scientists say the paintings are faithful to those found in the original cave

He says the process brought him closer to the original artists.

"If you spend hours and days and weeks, and you are trying to translate or imitate the gesture or work of another artist, you become more or less a part of him."

At the replica, Palaeolithic art specialist Jean Clottes stands surveying the work.

He was the first scientist to enter the cave, and has been president of the replica's scientific committee.

"I think the public are going to be very pleased with it because the quality is great and it is scientifically correct," he tells us.

More than 400 animals are painted in the original Chauvet cave

He says a replica is the best way to tell the modern masses about our prehistoric ancestors.

"They are not primitive people, they are people like us," he explains.

"Modern humans are 200,000 years old, at least, so 35,000 years ago was not such a long distance away."

He believes the cave was a spiritual place for these hunter gatherers, and the Ice Age animals represented on the rocks had a form of ritual or magic associated with them.

"(These people) had short lives that were quite different from ours, but from their art, we can see they were as intelligent as we are, that they had great artists and they had religion. They were close to us."

It's hoped that the replica will bring these ancient artists closer still, as their testimony to human culture and creativity opens to the crowds.

Or, at least, a copy of that testimony.

With so few people privileged enough to experience the real thing, prehistoric art must reach its audience through modern means.

Follow Rebecca, external and Stuart, external on Twitter

- Published8 October 2014

- Published15 June 2012

- Published1 September 2014