How Arctic ozone hole was avoided by Montreal Protocol

- Published

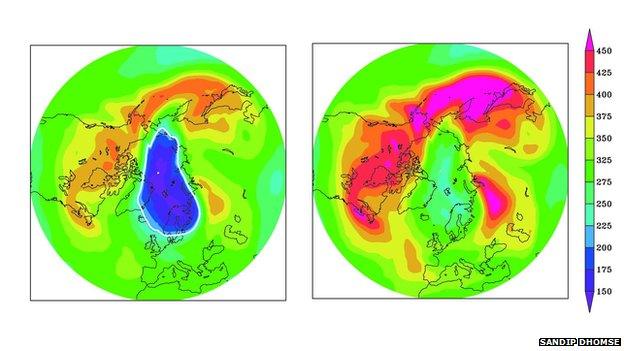

Arctic ozone without the Montreal Protocol (left) and following its implementation (right)

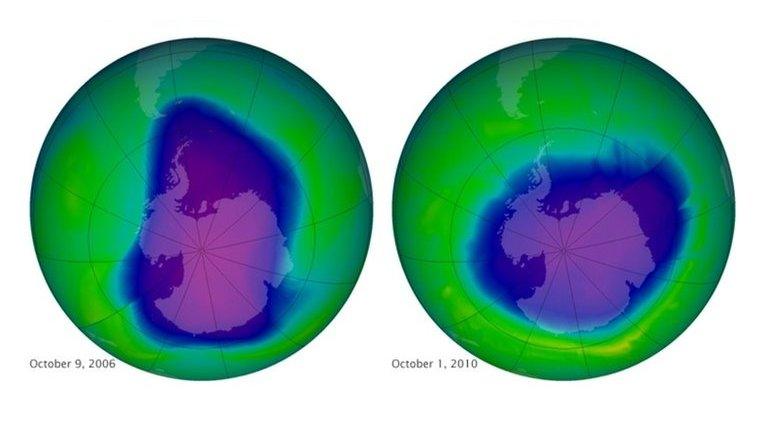

The Antarctic ozone hole would have been 40% bigger by now if ozone-depleting chemicals had not been banned in the 1980s, according to research.

Models also show that at certain times, a large hole would have opened up at the other end of the globe.

The Arctic hole would have been large enough to affect northern Europe, including the UK, scientists say.

The Montreal Protocol is regarded as one of the most important global treaties in history.

It was signed in 1987 after the discovery of a hole in the ozone layer above the Antarctic, the part of the upper atmosphere where ozone is found in high concentrations.

Ozone absorbs ultraviolet radiation, preventing most of it from reaching the ground.

Concerted international action led to the signing in Montreal of a UN agreement which phased out ozone-depleting chemicals, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) - once widely used in fridges and spray cans.

The new research, led by scientists at the University of Leeds, simulated what the ozone hole would have been like today if nothing had been done.

The largest hole in the ozone layer appears over Antarctica

Lead researcher, Martyn Chipperfield, said: ''We would be living in an era of having regular Arctic ozone holes.

''The Antarctic ozone hole which was discovered before 1987 would have got bigger and we would also have a fairly significant ozone depletion over mid-latitudes where there are high populations, including parts of Europe.''

Foresight

The study found that the Antarctic ozone hole would have grown in size by 40% by 2013, and the ozone layer would be thinner over middle latitudes of the northern hemisphere.

There would also have been a hole over the Arctic at times, which would have rivalled that of the Antarctic and would have affected northern Europe, including the UK.

The ozone loss would have led to increases in UV levels of about 10% in Australia, New Zealand and the UK, leading to more skin cancers, the study concludes.

Jonathan Shanklin of the British Antarctic Survey is one of three Cambridge scientists who discovered the ozone hole 30 years ago this month.

He said the Montreal Protocol was the UN's most successful treaty to date and observations from the British Antarctic base were showing signs of a ''recovery'' in ozone levels.

''The protocol provides a lesson for the future and we must hope that the coming climate change talks show the same foresight and result in a treaty that will benefit the whole planet,'' said Dr Shanklin.

Since the Montreal Protocol came into force, levels of chlorine and bromine containing ozone depleting chemicals have peaked and then declined.

The new research is published in the journal Nature Communications, external.

- Published16 May 2015

- Published11 September 2014

- Published12 December 2013