Philae comet lander wakes up, says European Space Agency

- Published

Scientists hope data from Philae could help explain the origins of life, as David Shukman reports

The European Space Agency (Esa) says its comet lander, Philae, has woken up and contacted Earth.

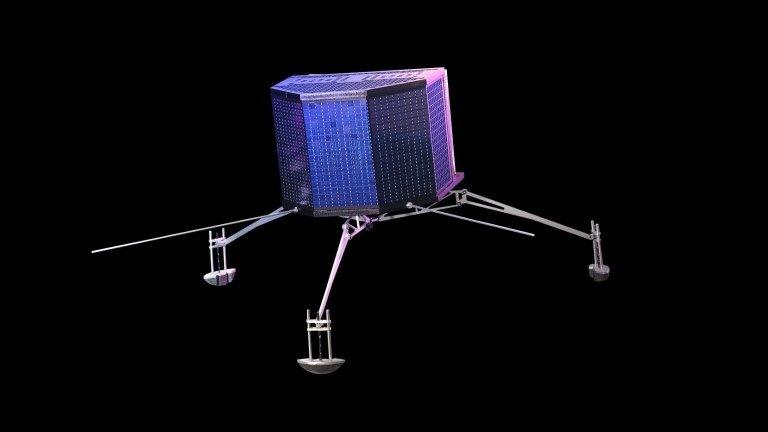

Philae, the first spacecraft to land on a comet, was dropped on to the surface of Comet 67P by its mothership, Rosetta, last November.

It worked for 60 hours before its solar-powered battery ran flat.

The comet has since moved nearer to the Sun and Philae has enough power to work again, says the BBC's science correspondent Jonathan Amos.

An account linked to the probe tweeted the message, "Hello Earth! Can you hear me?", external

On its blog, external, Esa said Philae had contacted Earth, via Rosetta, for 85 seconds on Saturday in the first contact since going into hibernation in November.

"Philae is doing very well. It has an operating temperature of -35C and has 24 watts available," said Philae project manager, Dr Stephan Ulamec.

Scientists say they now waiting for the next contact.

'Comet hitchhiker'

Esa's senior scientific advisor, Prof Mark McCaughrean, told the BBC: "It's been a long seven months, and to be quite honest we weren't sure it would happen - there are a lot of very happy people around Europe at the moment."

Philae was carrying large amounts of data that scientists hoped to download once it made contact again, he said.

"I think we're optimistic now that it's awake that we'll have several months of scientific data to pore over," he added.

Monica Grady says she hugged a taxi driver when she learned the lander had woken up

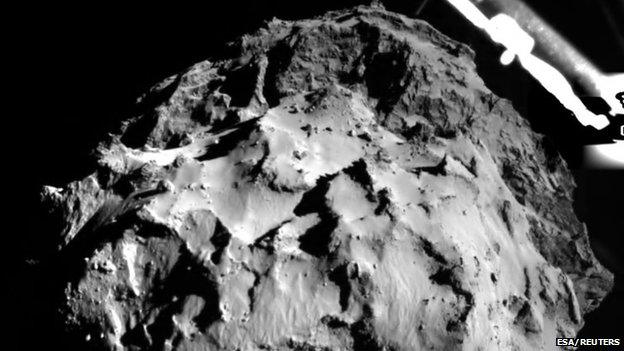

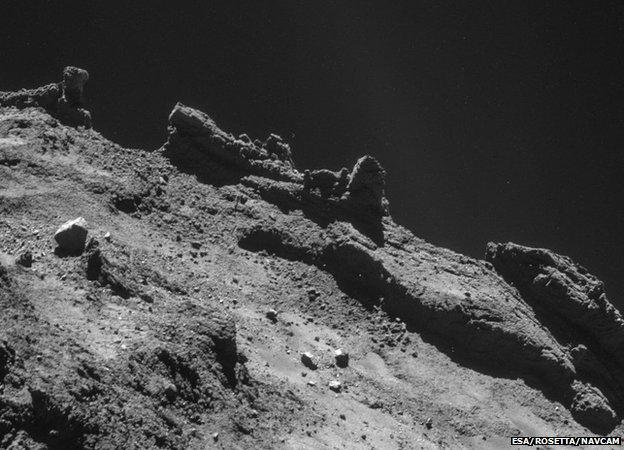

The lander snapped this photo of the comet during its descent last year

This is one of the most astonishing moments in space exploration and the grins on the faces of the scientists and engineers are totally justified, says BBC science editor David Shukman.

For the first time, we will have a hitchhiker riding on a comet and describing what happens to a comet as it heats up on its journey through space, he adds.

'Building blocks of life'

Philae is designed to analyse the ice and rocky fragments that make up the comet.

Prof Monica Grady from the Open University told the BBC that scientists now hoped to be able to carry out experiments to see whether comets were the source of life on Earth.

Comets contained a lot of water and carbon, and "these are the same sorts of molecules responsible for getting life going," she said.

"What we're trying to find out is whether the building blocks of life, in terms of water and carbon-bearing molecules, were actually delivered to Earth from comets."

Analysis: Jonathan Amos, BBC science correspondent

Philae will provide valuable information about the landscape of comet 67P

When Philae first sent back images of its landing location, researchers could see it was in a dark ditch. The Sun was obscured by a high wall, limiting the amount of light that could reach the robot's solar panels.

Scientists knew they only had a limited amount of time - about 60 hours - to gather data before the robot's battery ran flat.

But the calculations also indicated that Philae's mission might not be over for good when the juice did eventually run dry. The comet is currently moving in towards the Sun, and the intensity of light falling on Philae, engineers suggested, could be sufficient in time to re-boot the machine.

And so it has proved. Scientists must now hope they can get enough power into Philae to carry out a full range of experiments.

One ambition not fulfilled before the robot went to sleep was to try to drill into the comet, to examine its chemical make-up. One attempt was made last year, and it failed. A second attempt will now become a priority.

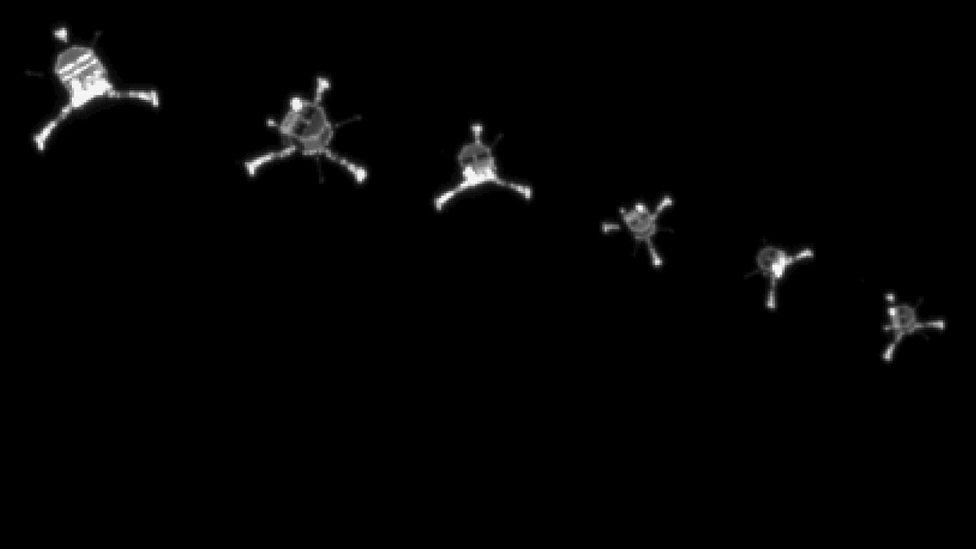

The Rosetta probe took 10 years to reach 67P, and the lander - about the size of a washing-machine - bounced at least a kilometre when it touched down.

Before it lost power, Philae sent back images of its surroundings that showed it was in a dark location with high walls blocking sunlight from reaching its solar panels.

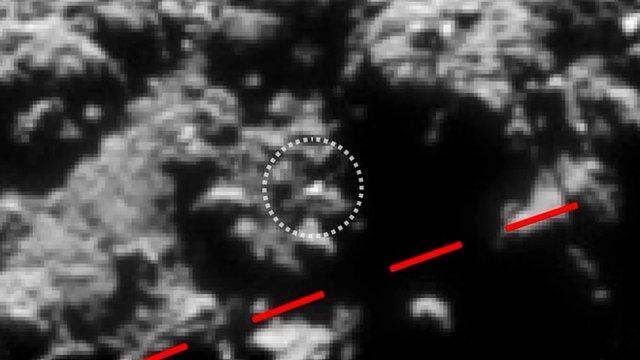

Its exact location on the duck-shaped comet has since been a mystery.

Comet 67P explained in 60 seconds

Esa had a good idea of where it was likely to be, down to a few tens of metres, but could not get Rosetta near enough to the comet to acquire conclusive pictures.

Continued radio contact should now allow precise coordinates to be determined, correspondents say.

Comet 67P is currently 205 million km (127 million miles) from the Sun, and getting closer.

It is due in August to get to a distance of about 186 million km, before then sweeping back out into the outer Solar System.

As it approaches the Sun, the comet is warming and its ices are melting.

This process will throw out a huge shroud of gas and dust, and if Philae can continue to keep working it will provide scientists with an extraordinary view of what is happening right at the surface of 67P.

- Published14 June 2015

- Published14 June 2015

- Published11 June 2015

- Published15 November 2014

- Published30 January 2015