Controllers now banking on Philae wake-up call

- Published

The European Space Agency (Esa) says it will conduct no more dedicated searches for its lost comet lander.

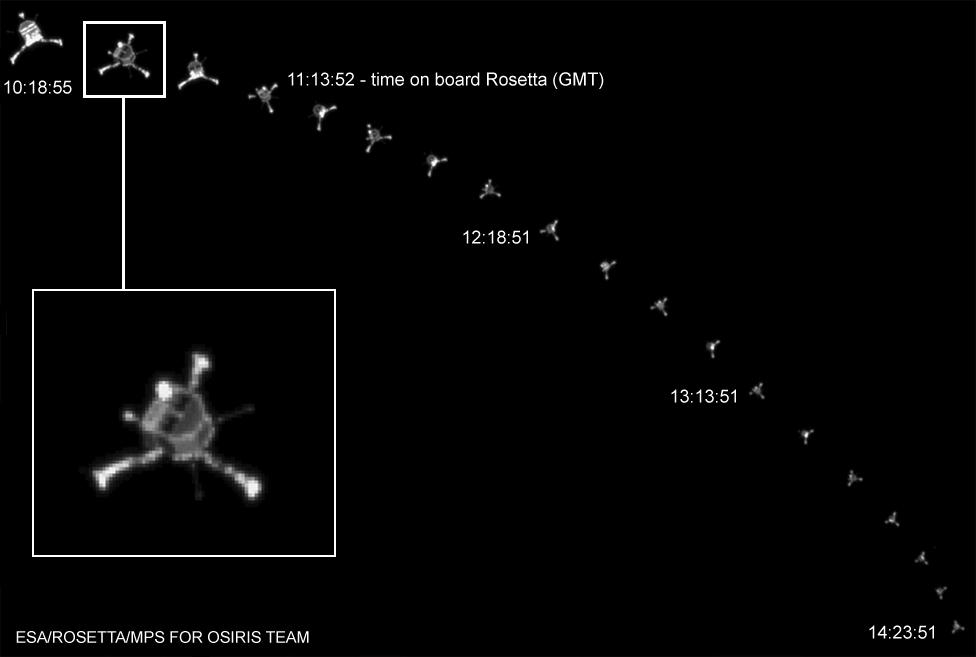

Esa has released the full image sequence of Philae moving away from its Rosetta mothership on 12 November, en route to the surface of 67P

The Philae probe made its historic touchdown on the 4km-wide "icy dirtball" 67P in November, but rapidly went silent when its battery ran flat.

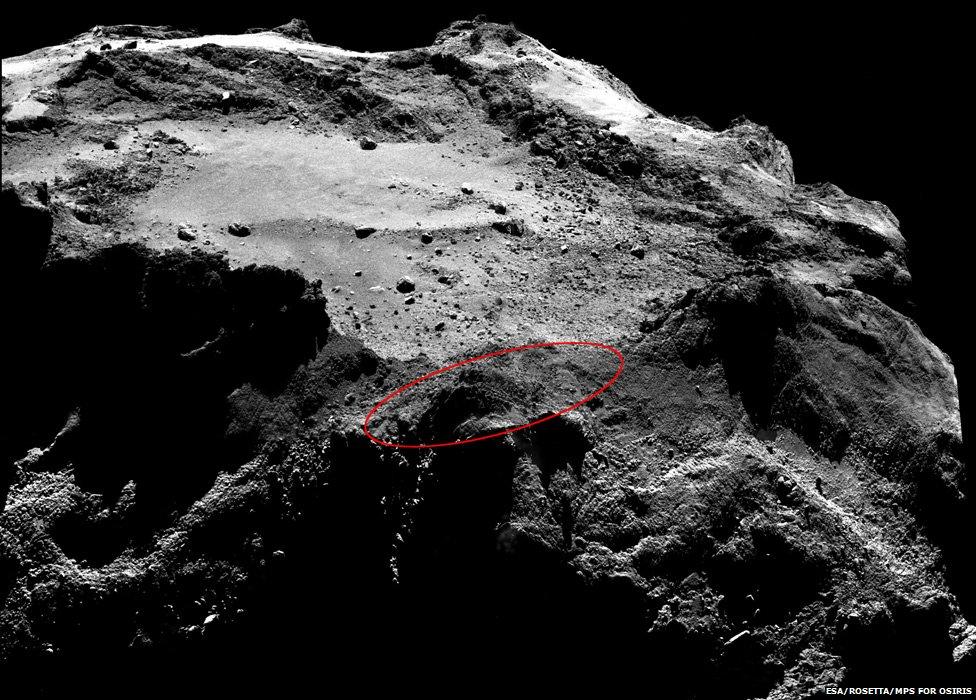

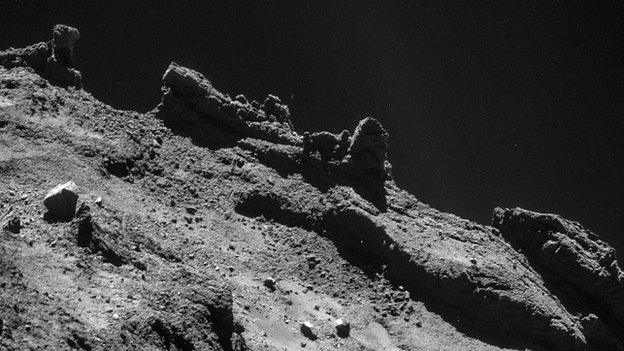

High-resolution pictures of the surface of the comet acquired by the orbiting Rosetta satellite have failed to identify the lander's location.

Controllers say they will simply wait now for Philae itself to call home.

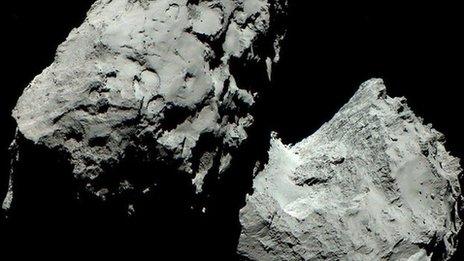

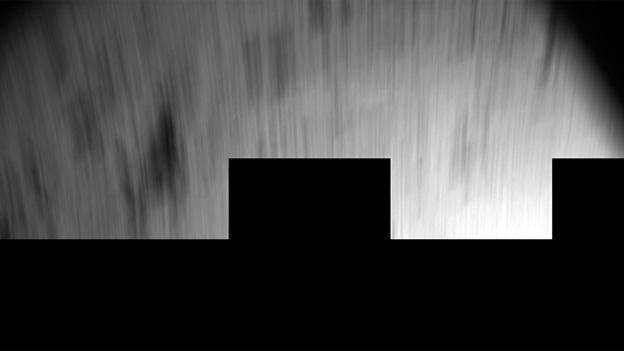

Rosetta captured Philae bouncing over and beyond the large depression called Hatmehit

They will begin listening in a few weeks' time with the hope that communications could be established in the May/June timeframe.

This would be when improved lighting conditions at the probe's presumed resting place provide enough power to run the onboard radio transmitter.

Esa on Friday released the full image sequence, external of the washing-machine-sized Philae drifting away from Rosetta at the start of November's descent to 67P.

Previously, only a few frames of this picture series had been made public.

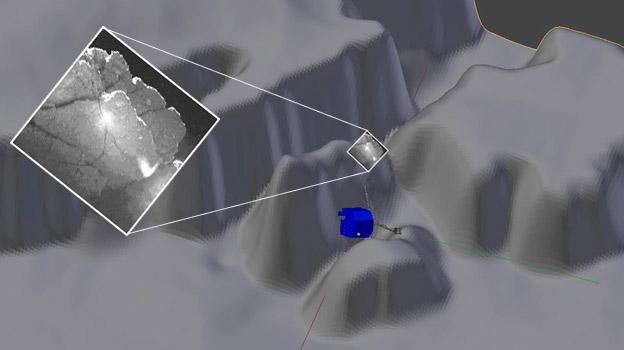

Researchers have a good idea of where the robot went subsequently. On touchdown, it bounced twice, crossing a large depression named "Hatmehit", before coming to rest in a dark ditch that has now been dubbed "Abydos".

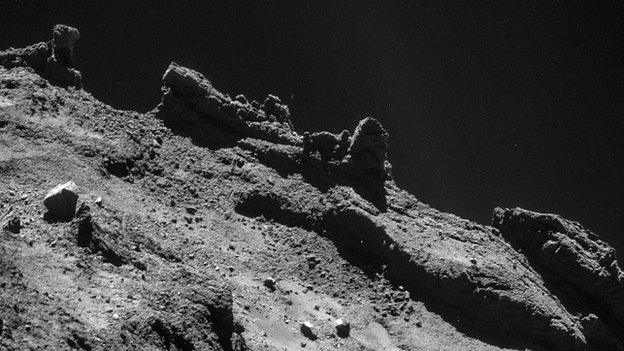

This much is clear from the pictures Philae took of its own surroundings. And this final resting place, the mission team believes, is just off the top of the "head" of the duck-shaped comet.

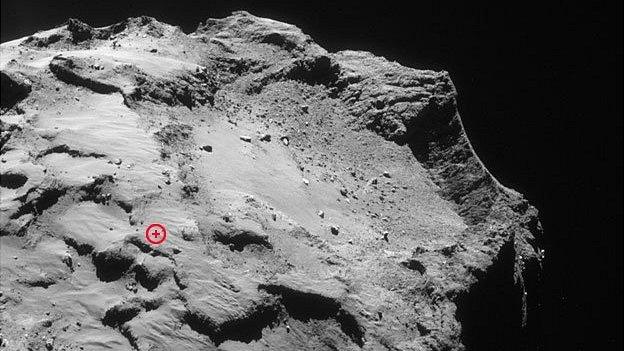

Data from a radio experiment running on the probe at the time of its shutdown suggests it should be found somewhere in a strip of terrain roughly 350m by 30m.

Rosetta photographed this general location on 12, 13 and 14 December, with each image then scanned by eye for any bright pixels that might be Philae. But no positive detection was made.

"Actually, we've seen several Philaes!" commented Stephan Ulamec, the lander manager at the German Space Agency (DLR). "And that's the problem: it's very difficult to distinguish Philae from surface features that resemble a little bit the shape of the lander."

Dr Ulamec said consideration was given to bringing in military imaging experts to help with the analysis, but it was concluded that looking for probes on comets was a very different task to hunting for camouflaged tanks.

Where is the Abydos site? All the indications are that Philae should be found somewhere in a strip of terrain roughly 350m by 30m

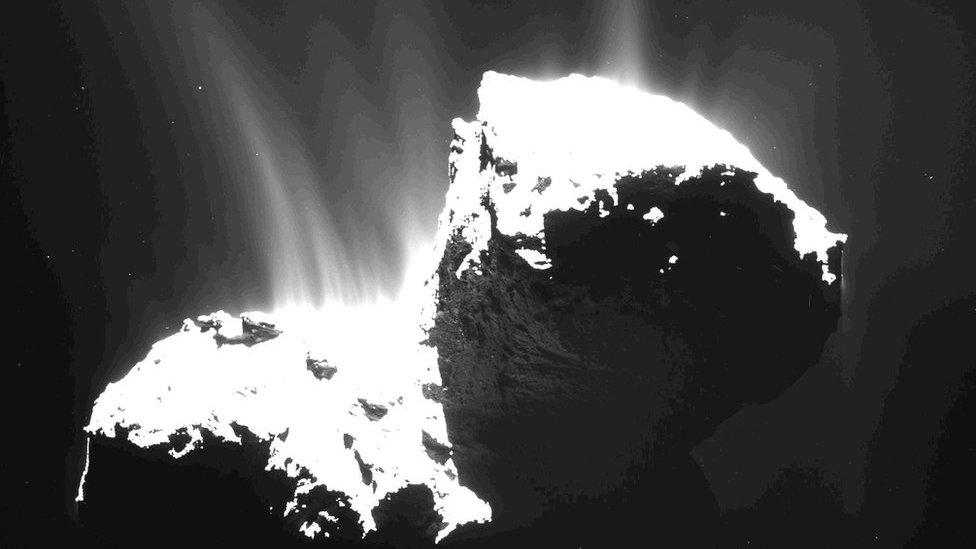

Esa plans now no further specific imaging searches. The comet, which is getting ever closer to the Sun (current distance is 364 million km), is expected very shortly to become much more active.

The warmth of our star will vaporise 67P's ices, generating huge jets of gas and dust in the process.

These jets make it harder to control Rosetta. Already, it has retreated from the 20km separation distance it was holding in December, and is now circling in a 30km-high orbit.

There is a plan to make a very close flyby on 14 February, which would see Rosetta sweep just 6km above the surface, but this will be a quick in-and-out pass that will go across the underside of the duck's body - far away from Philae's presumed resting place.

Controllers are banking on Philae itself making its position known.

This should happen as the comet's southern hemisphere comes out of winter in the coming weeks. Lighting conditions in the ditch will then get more intense, enabling the probe to first boot-up and then to communicate with Rosetta.

The routine will see Rosetta call out and listen for a reply. Initially, the energy needed to fire up its transmitter to make the response will see Philae fall straight back to sleep.

But in time, it should be gathering enough light on its solar panels to maintain a stable telecoms link and start to warm and charge the battery system as well.

This would see Philae resuming the science observations that were closed down just 60 hours after landing in November. As luck would have it, this might happen around August when the comet will be closest to the Sun (perihelion) and in its most active phase.

"There is good confidence, and of course all the teams are getting prepared for various scenarios," Dr Ulamec told BBC News. "It may be that they only get very limited periods of operation in the [dark] pocket, and they will have to plan for more modest science sequences."

Everyone must hope that Philae is not damaged by the cold that grips its position. Its electronics may be experiencing temperatures of minus 80C. That is some 20 degrees below the qualification limit set by the manufacturers. Thermal tension could start to loosen soldered joints. But good engineering requires large margins, so Philae should be safe.

The red cross marks the initial landing point. Philae then bounced right, and just over the horizon

A high wall, dubbed Perihelion Cliff, is thought to be blocking sunlight reaching Philae's solar panels

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 January 2015

- Published16 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published12 December 2014

- Published10 December 2014

- Published18 November 2014

- Published17 December 2014

- Published17 June 2015