Philae comet lander: The plucky robot is back

- Published

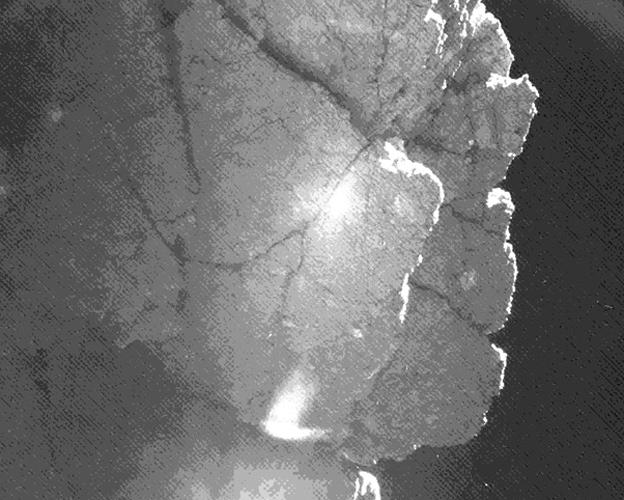

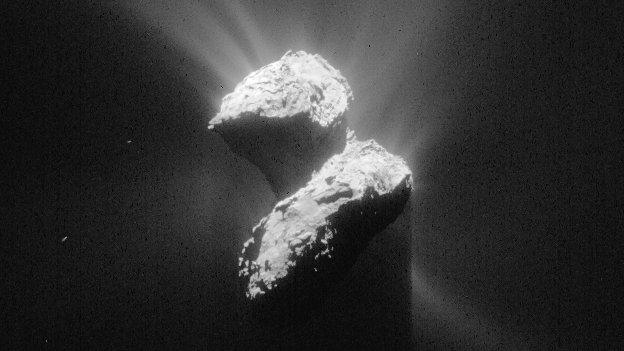

The lander has reawakened at an interesting time on 67P (pictured) as the comet nears the Sun

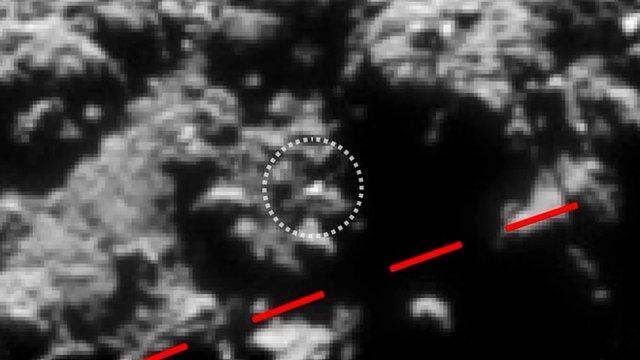

When Philae first sent back images of its landing location on Comet 67P, researchers could see it was in a dark ditch.

The Sun was obscured by a high wall, limiting the amount of light that could reach the robot's solar panels.

Scientists knew they only had a short amount of time - about 60 hours - to gather data before the lander's battery ran flat.

But the calculations also indicated that Philae's mission might not be over for good when the voltages did eventually flat-line.

67P is currently moving in towards the Sun, and engineers suggested that the intensity of light falling on Philae could be sufficient in time to re-boot the machine. And so it has proved.

The plucky robot that enthralled the world is back.

Scientists have expressed joy at the lander's re-awakening

The sense of relief in the mission team must be immense. Many people had worried that the very low temperatures endured by the lander on the icy comet could have done irreparable damage to its electronic circuitry.

The fact that both its computer and transmitter have fired up to contact home indicates that the engineering has stood up remarkably well in what must have been really quite challenging conditions these past seven months.

Scientists must now hope they can get enough power into Philae to carry out the full range of experiments.

One ambition not fulfilled before the robot went to sleep in November was to try to drill into 67P, to examine its chemical make-up.

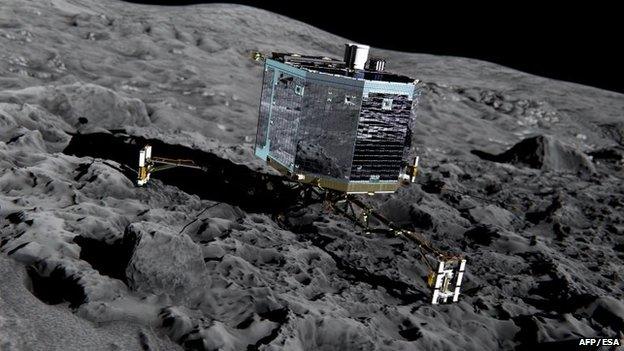

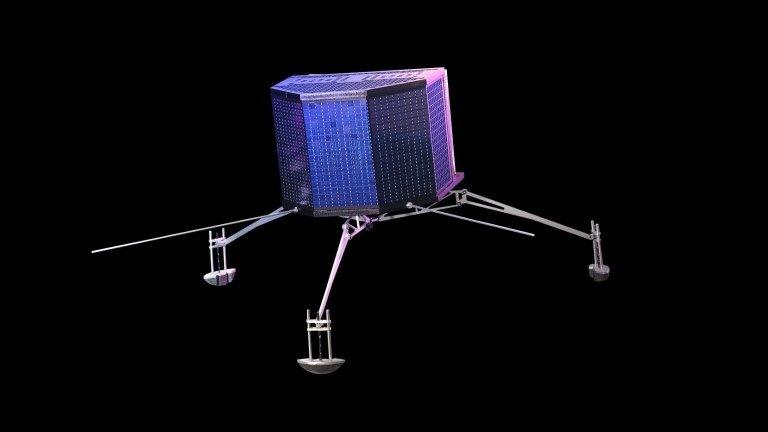

Philae is designed to analyse the ice and rocky fragments on the comet

An attempt was made last year, but it did not appear to work. Either the tool picked up nothing, or for some reason the gathered sample did not make it into the on-board laboratories.

Either way, a second bid to drill the surface will now become a priority.

But some experiments will be more power-hungry than others, and drilling is one of these.

Engineers must establish what they can, and cannot, accomplish with the revitalised Philae.

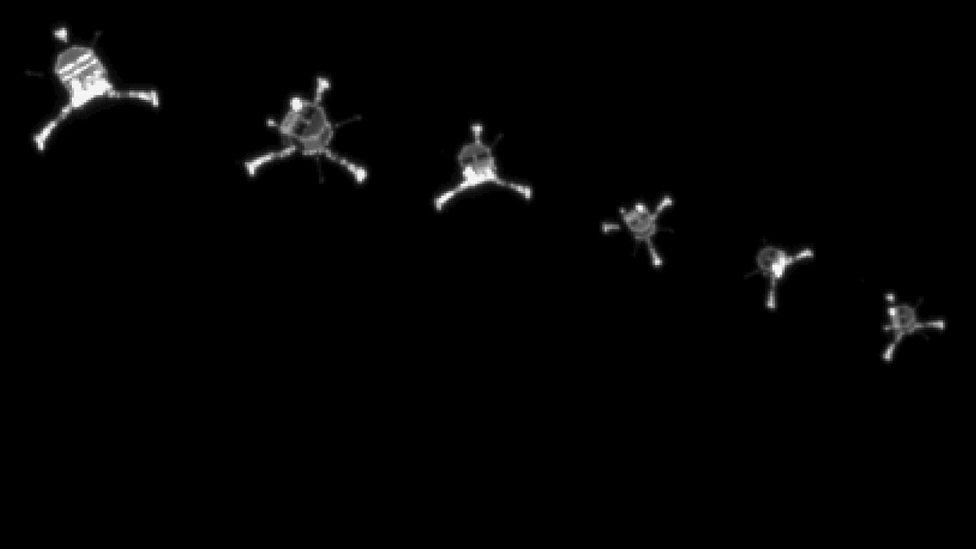

Philae landed in a ditch where sunlight was obscured by a high wall

The robot could yet turn out to be one of the biggest good-luck stories in the history of space exploration.

Had Philae landed precisely where it was targeted back in November, it would have been sitting on an open plain. Solar generation conditions would have been perfect from the outset.

But even if it had succeeded, death would have come relatively soon. Indeed, the pre-landing analysis was that Philae would succumb to overheating on the plain after perhaps a couple of months.

As it was, the robot bounced into its shaded ditch and went into hibernation. And that long slumber means it has now come back to life at a far more interesting time on Comet 67P - just as it nears perihelion, the closest point to the Sun.

If you had to pick a time to have a robot on the surface, it would be right now. 67P's ices are being energised, and are throwing huge jets of gas and dust into space.

A fully recovered Philae promises a scientific extravaganza beyond what anyone dared believe was possible when it first touched down.

- Published14 June 2015

- Published14 June 2015

- Published14 June 2015

- Published11 June 2015

- Published15 November 2014

- Published30 January 2015