Rosetta spies cometary sinkholes

- Published

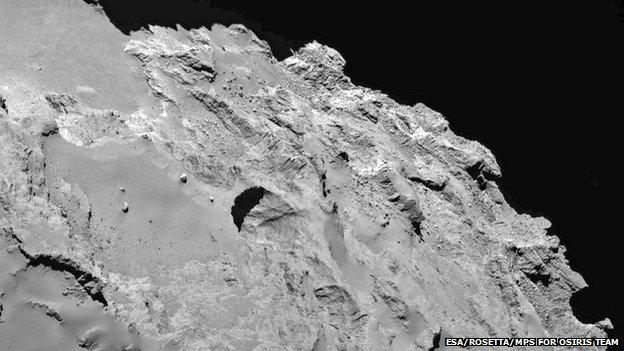

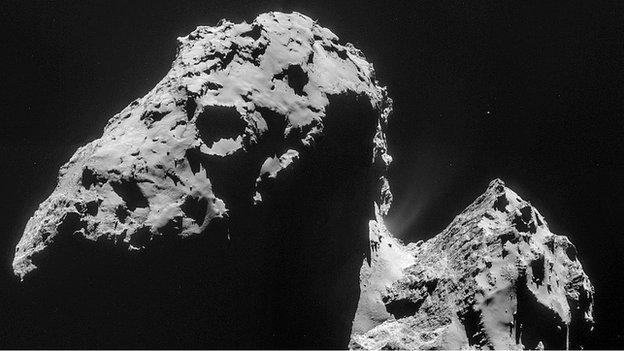

Collapse exposes the walls that can then also be eroded, eventually softening the pit's appearance

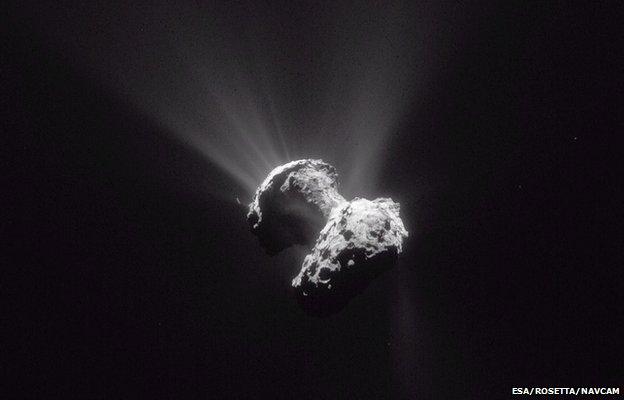

The comet being studied by Europe’s Rosetta probe is riddled with pits that formed much like sinkholes here on Earth, say scientists.

They think material under the surface of the icy dirt-ball vaporises in places, resulting in voids that will then no longer support the crust above.

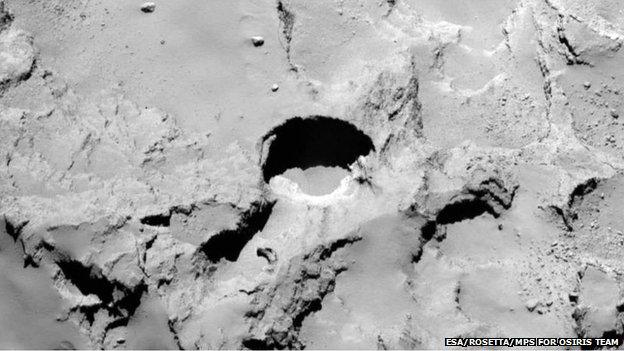

Ceiling collapse produces cylindrical holes that can be more than 100m deep.

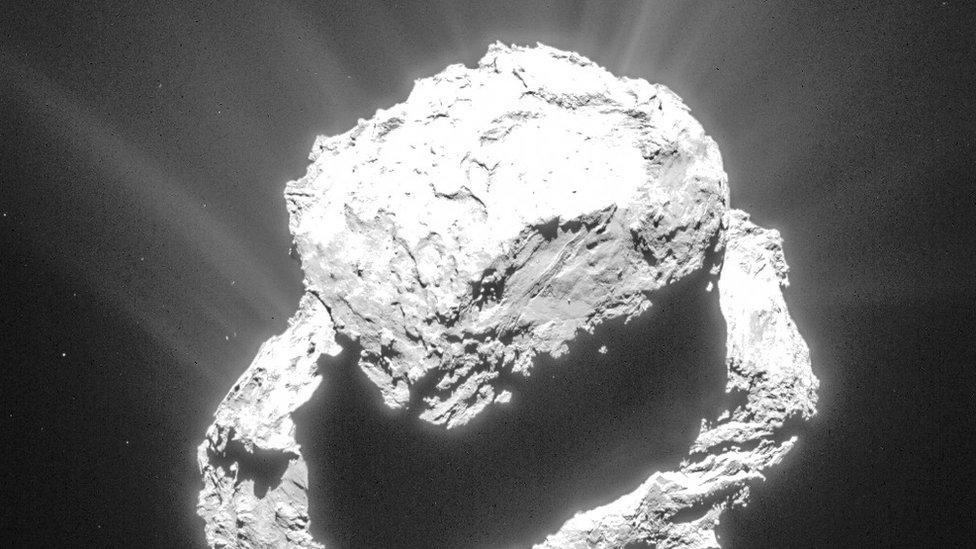

Mission researchers say the pits give a view of the inside of 67P.

"They are almost as deep as they are wide," said Jean-Baptiste Vincent, from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany.

"The largest one is about 200m wide and 200m deep.

"It's amazing because it gives us the possibility to look inside the comet for the first time," he told BBC News.

Dr Vincent's team reports its observations in this week's Nature journal, external.

The pits seem to have smooth, flat, dusty floors

Sinkholes are a common feature on Earth, especially in landscapes containing easily erodible rock types such as limestone.

Rains and watercourses can slowly eat away at underlying sediments, producing cavities that eventually break through to the surface.

The scientists working on the European Space Agency's Rosetta probe, external think something similar is happening on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Sinkholes are a common feature here on Earth

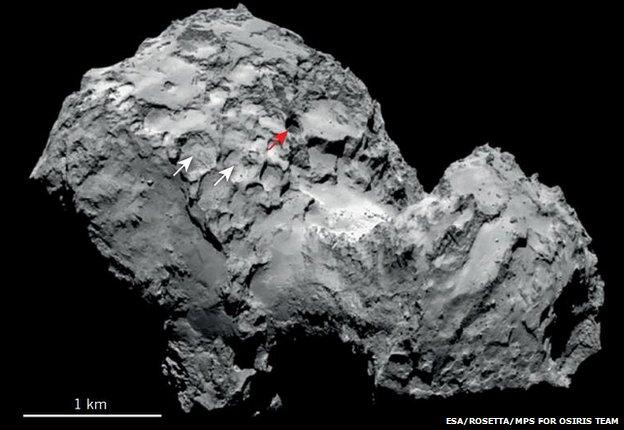

Eighteen pits of interest have been identified on the lit, northern hemisphere of the 4km-wide object.

The theory being posited is that as the comet moves in towards the Sun it will heat up, and buried volatiles will be driven off, opening up hollows.

These voids may already exist to some extent in what is known to be a highly porous body, but the lost volatiles will only exacerbate the situation.

And the dusty, rocky ceilings above the caverns will not be able to support their own weight - even in the low-gravity environment of 67P - and will eventually fall inwards.

This exposes the walls of the pits to direct sunlight, and the ices there are then vaporised.

Pictures from Rosetta clearly show jets of gas and dust shooting away from the walls.

Over time, the sinkholes will likely open out into shallower basins, and these basins will probably also merge.

This knowledge becomes useful for relating the ages of different terrains, because areas that contain many open basins will almost certainly be older than ones with discrete pits.

The pits (red arrow) likely open out into shallower basins (white arrows) over time

This whole process, the team believes, has a major influence on the look of the craggy, duck-shaped comet.

Of key interest to the scientists is the view the pits are giving of the interior of 67P, and the opportunity this offers to study the object's fundamental structure.

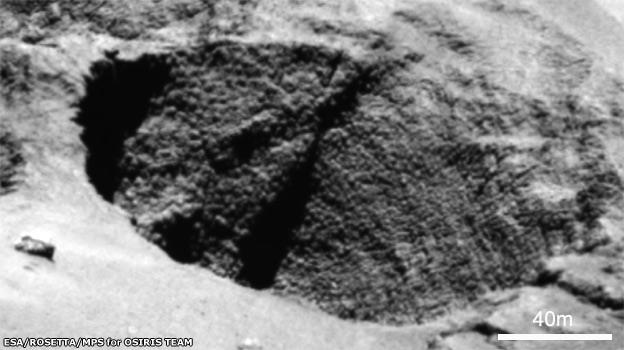

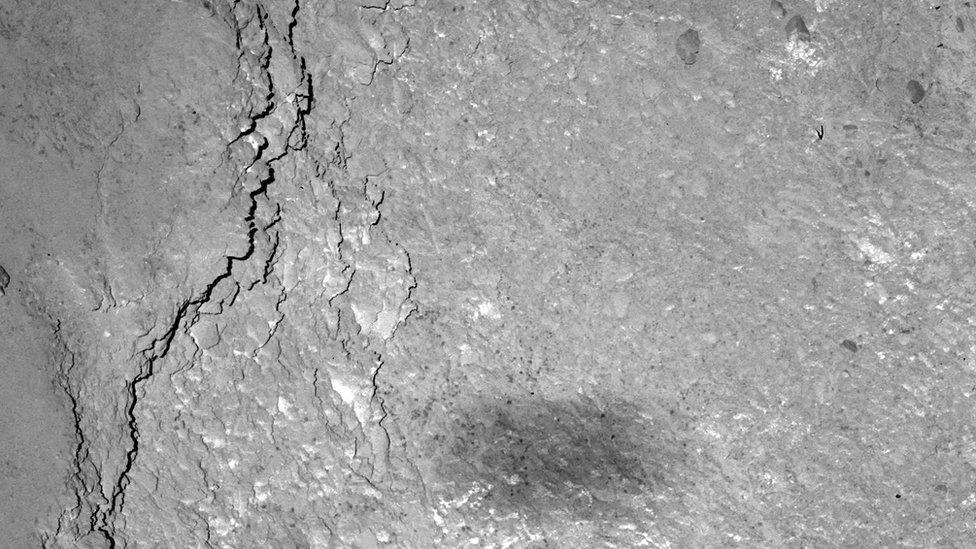

Mission researchers have previously reported the so-called "goosebumps" on the comet. These 1-3m lumps and bumps may be the original icy building blocks that came together to form 67P more than 4.5 billion years ago.

"All the goosebumps we have observed on the comet – they are inside these pits," said Dr Vincent.

A fascinating texture: Comet 67P's "goosebumps" have a preferred scale of about 1-3m

Rosetta and the comet are currently about 290 million km from Earth and heading in towards the Sun.

Next month marks perihelion, when 67P makes its closest approach to our star, before then sweeping back out into the outer Solar System.

The separation between the comet and the Sun at that point will be some 186 million km, and the increased warmth will drive still more activity. Already, the object is producing spectacular jets, and they will only get more intense.

In addition to making its own observations, Rosetta is also talking to the lander, Philae, which it dropped on to the surface of the comet last November.

Philae has recently come back to life after a period in hibernation.

But Esa controllers need to establish a stable communications link through Rosetta before the little lander can be commanded to resume science observations.

The comet is currently throwing off spectacular jets of gas and dust

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published19 June 2015

- Published20 April 2015

- Published20 March 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published3 March 2015

- Published22 January 2015