Martian salt streaks 'painted by liquid water'

- Published

- comments

The US space agency says it believes dark stripes on Mars are flows of water.

Scientists think they can now tie dark streaks seen on the surface of Mars to periodic flows of liquid water.

Data from a Nasa satellite shows the features, which appear on slopes, to be associated with salt deposits.

Crucially, such salts could alter the freezing and vaporisation points of water in Mars's sparse air, keeping it in a fluid state long enough to move.

Luju Ojha and colleagues report the findings in the journal Nature Geoscience, external.

There are implications for the existence of life on the planet today, because any liquid water raises the possibility that microbes could also be present. And for future astronauts on Mars, the identification of water supplies near the surface would make it easier for them to "live off the land".

"It may decrease the cost - and increase the resilience - of human activity on the planet," co-author Mary-Beth Willhelm, from the Nasa Ames Research Center in California, said in a US space agency media briefing on Monday.

Secret source

Researchers have long wondered whether liquid water might occasionally flow across the surface today.

It is not a simple proposition, because the temperatures are usually well below zero Celsius and the atmospheric pressure is so low that any liquid H2O will rapidly boil.

But the observation over the past 15 years of gullies and surface streaks that appear to change with the seasons has heightened the speculation.

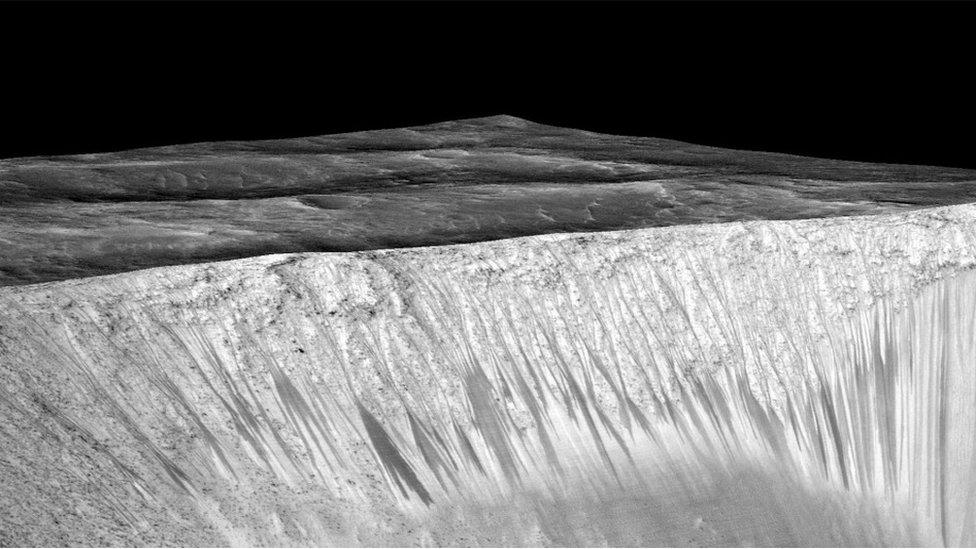

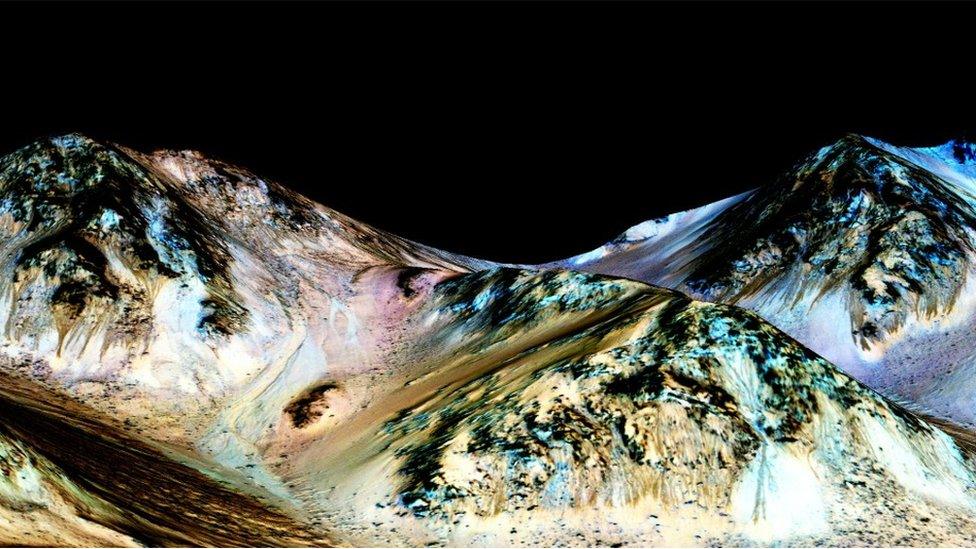

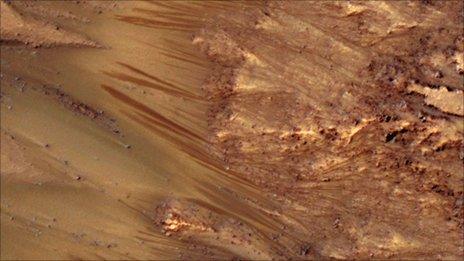

Dark streaks: Recurring slope lineae can be hundreds of metres long

The images on this page are perspective views generated by a computer from MRO data

Mr Ojha, a PhD student at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has now presented data from the US space agency's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that seems to solve the conundrum.

MRO has an instrument called Crism that can determine the chemistry of surface materials.

It has looked at four locations where dark streaks are seen to come and go during Martian summer months. These streaks, called "recurring slope lineae" (RSL), were well known to Mars scientists and were suspected - but not proven - to be associated with trickling water.

"We know from prior investigations that these features form on Mars," Mr Ojha told journalists at the briefing.

"However, the key evidence was missing until now - and that was their chemical identity."

Alfred McEwen, a senior member of the orbiter team and a professor of planetary geology at the University of Arizona, agreed: "We had no direct detection of water; that was just our best guess as to what these were."

Now, Crism has demonstrated that the RSLs are covered with salts.

They are salts - magnesium perchlorate, chlorate and chloride - that can drop the freezing point of water by 80 degrees and its vaporisation rate by a factor of 10.

The combination allows briney water to stay stable long enough to trickle down hillsides and crater walls.

Quite where the water is coming from to make the streaks is still unclear, however. The locations of RSL are mostly equatorial, and any stored water in this region of Mars, perhaps in the form of ice, is thought to exist only at great depth.

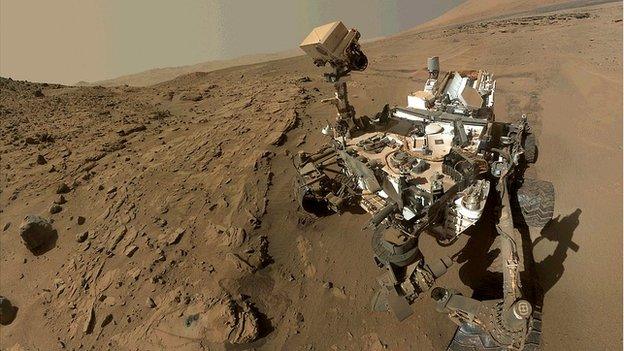

One possibility is that the salts actually pull the water out of the atmosphere. The Curiosity rover has found some strong pointers to this mechanism. But again, it is not known whether there is a sufficient supply in the air to facilitate a decent flow.

Dr Jim Green: "Under certain circumstances liquid water has been found on Mars"

Another theory is that local aquifers are breaking up to the surface, but this does not really fit with streaks that appear from the tops of peaks.

It is conceivable that streaks are being formed from different sources in different parts of Mars.

Contamination question

Dr Joe Michalski is a Mars researcher at the Natural History Museum in London. He called the announcement an exciting development, especially because of its implications for the potential of microbes existing on the planet today.

"We know from the study of extremophiles on Earth that life can not only survive, but thrive in conditions that are hyper-arid, very saline or otherwise 'extreme' in comparison to what is habitable to a human. In fact, on Earth, wherever we find water, we find life. That is why the discovery of water on Mars over the last 20 years is so exciting."

An interesting consequence of the findings is that space agencies will now have some extra thinking to do about where they send future landers and rovers.

Current internationally agreed rules state that missions should be wary of going to places on Mars where there is likely to be liquid water. Spacecraft would need to be thoroughly sterilised beforehand.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 April 2015

- Published9 December 2014

- Published26 September 2013

- Published4 August 2011

- Published8 December 2011

- Published25 June 2010