Martian water streaks present exploration challenge

- Published

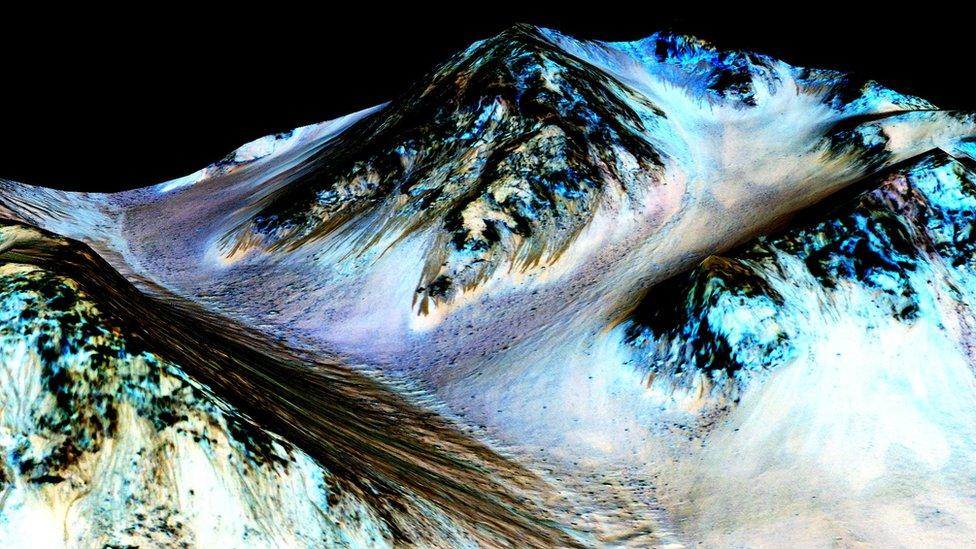

The dark streaks - or "recurring slope lineae" - result from the movement of liquid water, Nasa scientists say

Wherever there's water, there's a good chance life can thrive.

H2O is the "lubricant" of biochemical reactions, and Nasa's announcement that liquid water flows under certain circumstances on the Red Planet will heighten expectation that this normally freezing, desiccated world might just provide a foothold for microbial organisms.

We know from Earth that life is tenacious.

Even in super-salty or acidic lakes, toxic dumps, and even boiling pools, some bugs are capable of eking out an existence. We call them extremophiles.

The immediate reaction of many to Monday's announcement will be to want to go look for extremophiles on Mars - to send either scientific instruments to examine the briney streaks in situ, or better still to bring some rock and soil samples back to Earth labs for analysis. But that is easier said than done.

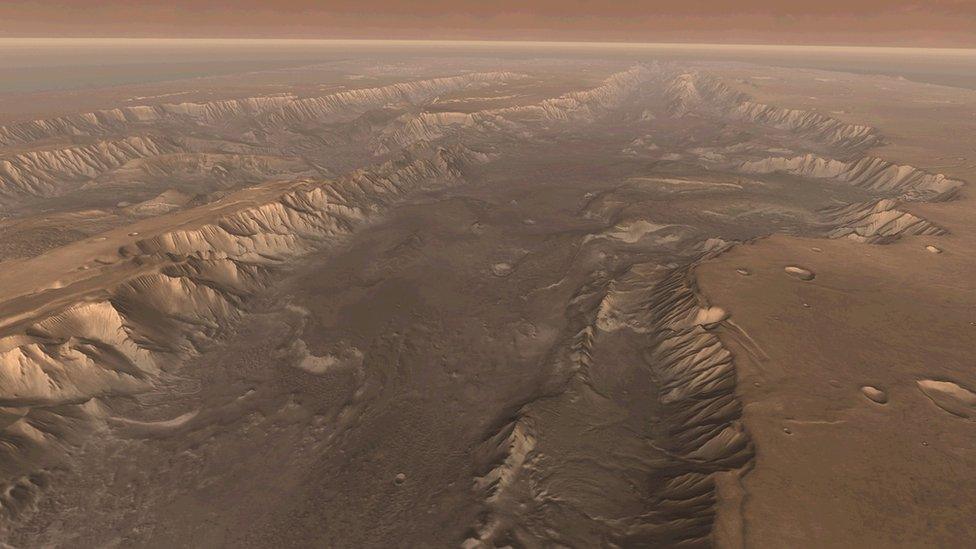

For one thing, many of the locations where these dark streaks are located are in pretty inaccessible places. They run down the steep slopes of peaks and crater walls. Quite a number are inside the giant canyon system Valles Marineris.

The probes we've sent to Mars hitherto have all been targeted at flat plains. For obvious reasons. The precision of our landing technology is such that we cannot yet guarantee to put down "on the button".

Many of the water locations are inside the giant canyon system Valles Marineris

Even the brilliant "skycrane" that delivered the Curiosity rover to the floor of Gale Crater in 2012 had a landing error ellipse of 7km by 20km. That's amazing after a journey of 570 million km, but the risk of slamming into Gale's big central mountain, or its crater walls, meant that engineers had no choice but to play safe and aim for flatlands that then required months of driving to get to the rover's primary science location.

Landing tech will improve, of that there is no doubt. And the copy of Curiosity that Nasa will send to Mars in 2020 expects to shrink the ellipse considerably.

But assuming you can put down safely, how do you get a robot to work on a steep slope? Present day rovers can only handle gentle inclines. Completely new types of probes would be needed - robots that can climb or even clamber over difficult terrain.

And as if that's not all hard enough, getting to investigate the enigmatic streaks faces another big challenge - and that is the risk of contamination.

Different types of robot design will be needed to venture across more difficult terrain

The major space agencies, from the likes of the US, Russia and Europe, belong to what's called the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), which has drawn up guidelines for exploration.

Adhered to under international treaty, these guidelines describe the sort of cleanliness required by spacecraft, depending on where they want to go and what they want to do.

A flyby of a planet carries minimal risk, but Mars, with its history of water and its potential for life, finds itself in one of the top categories; and the streaks constitute a special region where extra care would be required.

There's good reason to try to be really clean. We don't want to carry earthly microbes to a pristine environment because that will prevent us from answering definitively one of the most fundamental questions in science: is there, or has there ever been, life on a planet other than our own?

Imagine a dirty spacecraft at Mars claiming a "positive detection" of indigenous microbes. That claim would rightly be dismissed with the criticism that the robot had merely seen evidence for Earth microbes that had hitched a lift to Mars.

You might think that spacecraft that have spent months travelling to the Red Planet, in the vacuum of space, exposed to copious amounts of ultraviolet light and damaging cosmic radiation, would effectively be fully sterilised by the time they arrive at the surface. But the experiments by astronauts at the Moon and on the exterior of the space station show otherwise. Some of the simplest organisms can be incredibly robust.

COSPAR's Planetary Protection guidelines, external would demand that any robot sent to water-made streaks - "recurring slope lineae" (RSL) to give them their proper name - had the highest level of cleanliness even before launch.

That is difficult, complex and expensive to achieve, but very doable. The Viking landers that went to Mars in the 1970s to look for life managed to attain this level of control, said Gerhard Kminek, the chair of the COSPAR Panel on Planetary Protection.

"These are not new concepts. For 13 years we've had measures in the policy to deal with special regions and these have been reviewed, and in fact they were updated only last week. We had a meeting in Switzerland where we discussed anything with consequences for the policy, and of course RSLs are part of that. The point is we do not want to spend a lot of money trying to detect life on Mars only to end up just detecting terrestrial (Earth) organisms."

One of the twin Viking landers being placed in the sterilisation oven prior to its despatch to Mars