Fossil teeth place humans in Asia '20,000 years early'

- Published

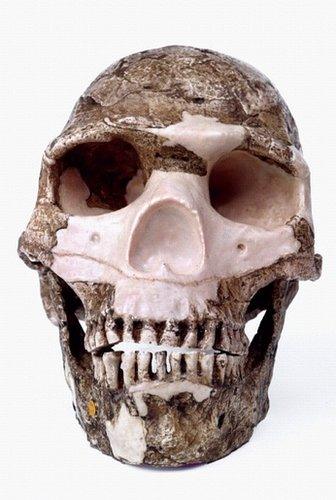

The 47 human teeth were found sealed in a cave, beneath 80,000-year-old stalagmites

Fossil finds from China have shaken up the traditional narrative of humankind's dispersal from Africa.

Scientists working in Daoxian, south China, have discovered teeth belonging to modern humans that date to at least 80,000 years ago.

This is 20,000 years earlier than the widely accepted "Out of Africa" migration that led to the successful peopling of the globe by our species.

Details of the work are outlined in the journal Nature, external.

Several lines of evidence - including genetics and archaeology - support a dispersal of our species from Africa 60,000 years ago.

Early modern humans living in the horn of Africa are thought to have crossed the Red Sea via the Bab el Mandeb straits, taking advantage of low water levels.

All non-African people alive today are thought to derive from this diaspora.

Now, excavations at Fuyan Cave in Daoxian have unearthed a trove of 47 human teeth.

Ancient diaspora

"It was very clear to us that these teeth belonged to modern humans [from their morphology]. What was a surprise was the date," Dr María Martinón-Torres, from University College London (UCL), told BBC News.

"All the fossils have been sealed in a calcitic floor, which is like a gravestone, sealing them off. So the teeth have to be older than that layer. Above that are stalagmites that have been dated using uranium series to 80,000 years.

This means that everything below those stalagmites must be older than 80,000 years old; the human teeth could be as old as 125,000 years, according to the researchers.

Modern humans reached the Levant 125,000 years ago, but this migration has been regarded as a failed foray outside Africa

In addition, the animal fossils found with the human teeth are typical of the Late Pleistocene - the same period indicated by the radioactive dating evidence.

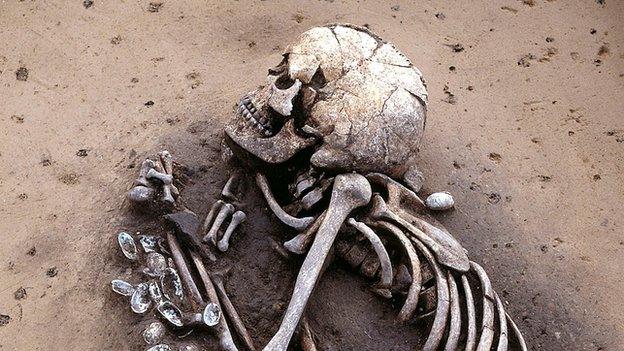

Some fossils of modern humans that predate the Out of Africa migration are already known, from the Skhul and Qafzeh caves in Israel. But these have been regarded as part of a failed early dispersal of modern humans who probably went extinct.

However, the discovery of unequivocally modern fossils in China clouds the picture.

"Some researchers have proposed earlier dispersals in the past," said Dr Martinón-Torres.

"We really have to understand the fate of this migration. We need to find out whether it failed and they went extinct or they really did contribute to later people.

"Maybe we really are descendents of the dispersal 60,000 years ago - but we need to re-think our models. Maybe there was more than one Out of Africa migration."

'Game-changer'

Prof Chris Stringer, from London's Natural History Museum said the new study was "a game-changer" in the debate about the spread of modern humans.

"Many workers (often including me) have argued that the early dispersal of modern humans from Africa into the Levant recorded by the fossils from Skhul and Qafzeh at about 120,000 years ago was essentially a failed dispersal which went little or no further than Israel."

"However, the large sample of teeth from Daoxian seem unquestionably modern in their size and morphology, and they look to be well-dated by uranium-thorium methods to at least 80,000 years. At first sight this seems to be consistent with an early dispersal across southern Asia by a population resembling those known from Skhul and Qafzeh.

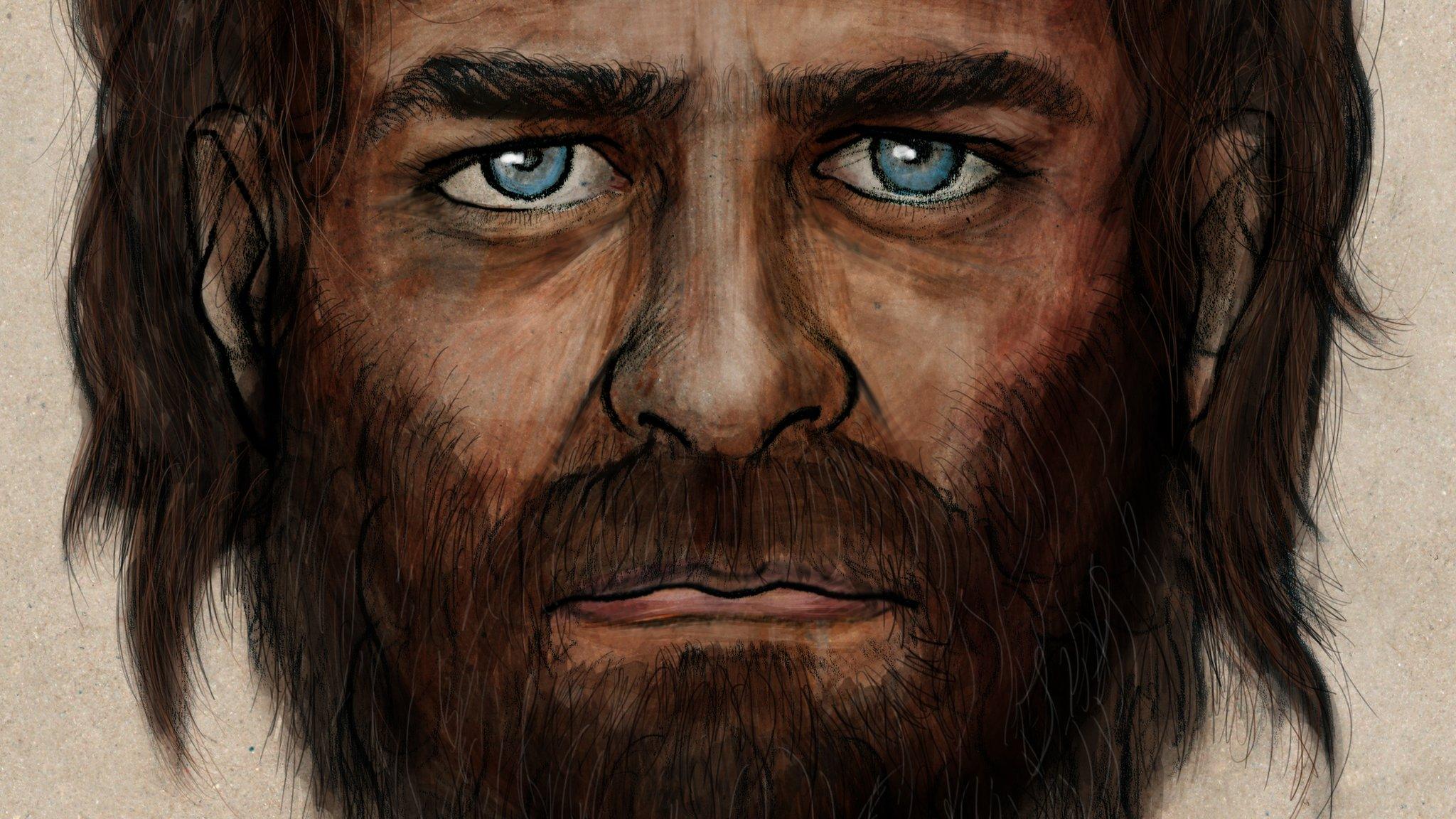

"But the Daoxian fossils resemble recent human teeth much more than they look like those from Skhul and Qafzeh, which retain more primitive traits. So either there must have been rapid evolution of the dentitions of a Skhul-Qafzeh type population in Asia by about 80,000 years, or the Daoxian teeth represent a hitherto-unsuspected early and separate dispersal of more modern-looking humans."

Dr Pontus Skoglund, from the department of genetics at Harvard Medical School, told BBC News: "The genetic evidence we have puts strong constraints on some aspects of human history, but less so on the timing of the out of Africa event. Most genetic reconstructions based on modern data relies on assumptions on the mutation rate, for which there are still some real uncertainties.

"In terms of direct genetic evidence, we already have a 45,000 year-old genome from Siberia (Ust Ishim) and a ~40,000 year old individual from Europe (Oase) that are consistent with being from now-mostly-extinct lineages. "

"The conclusion is perhaps that the genetics does allow an 80,000 year old East Asian population to contribute some ancestry to present-day people, but I think not very much. It is a very interesting discovery that is hard to fit in our current thinking, but not impossible. We are just starting to cope with this data point."

Dr Martinón-Torres said the study could also shed light on why it took Homo sapiens another 40,000 years to settle Europe.

Perhaps the presence of the Neanderthals kept our species out of westernmost Eurasia until our evolutionary cousins started to dwindle in number. However, it's also possible that modern humans - who started out as a tropical species - were not as well-conditioned as the Neanderthals for the icy climate in Europe.

She noted that while modern humans occupied the warmer south of China 80,000 years ago, the colder regions of central and northern China appear to be settled by more primitive human groups who may have been Asian relatives of the Neanderthals.

Follow Paul on Twitter, external

- Published8 October 2015

- Published2 March 2015

- Published17 September 2014

.jpg)

- Published13 February 2014

- Published27 January 2014

- Published28 January 2015