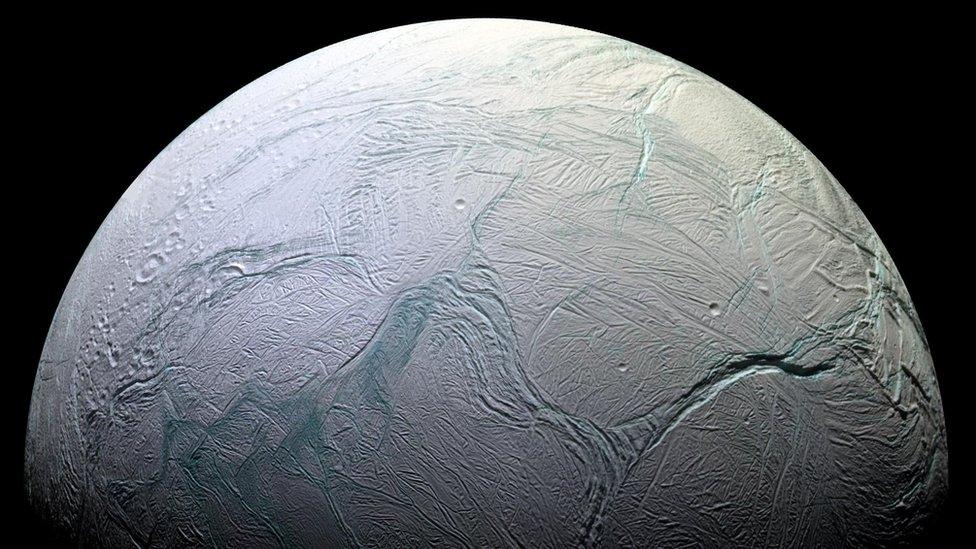

Cassini probe sweeps over Saturn's moon Enceladus

- Published

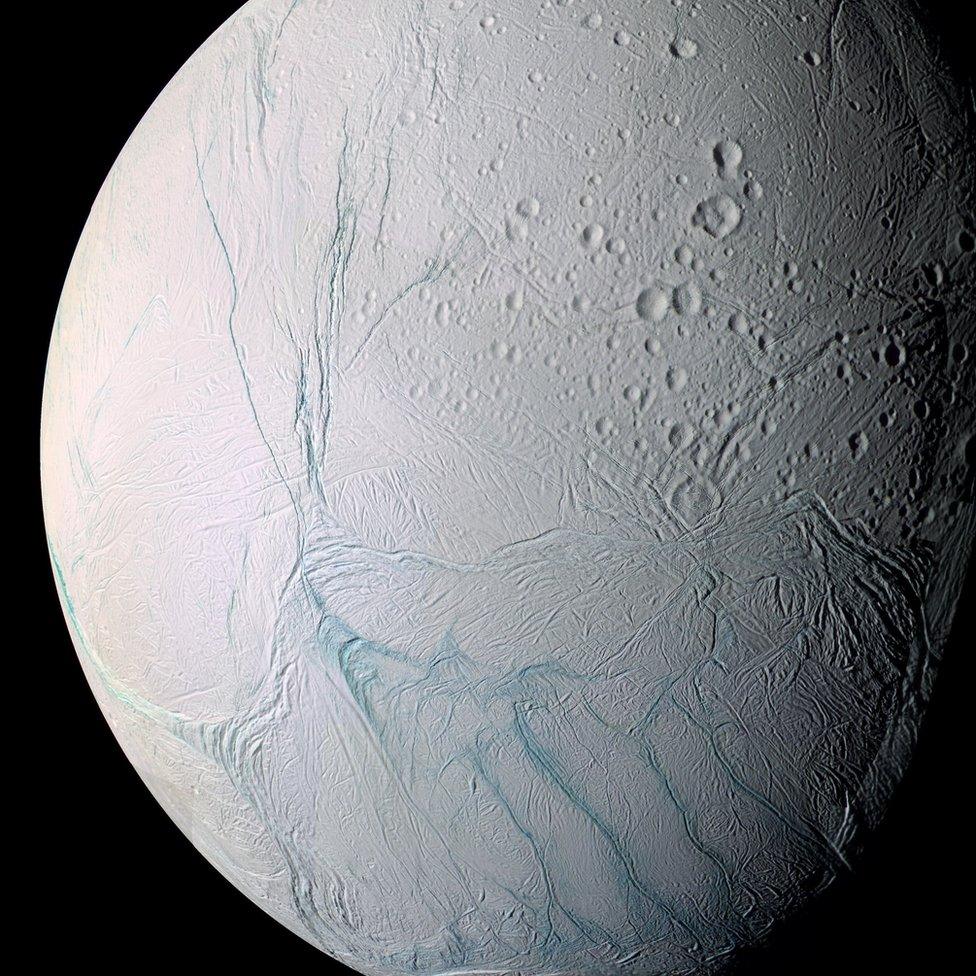

Enceladus has been one of the revelations of the entire Cassini mission

The Cassini probe has made a daring close flyby of Enceladus, an ice-rich moon of Saturn.

The Nasa craft swept just 50km above the moon's surface in a final attempt to "taste" the chemistry of water jets spewing from its south pole.

Enceladus has produced a series of major discoveries that mean it is now considered one of the most promising places to find life beyond Earth.

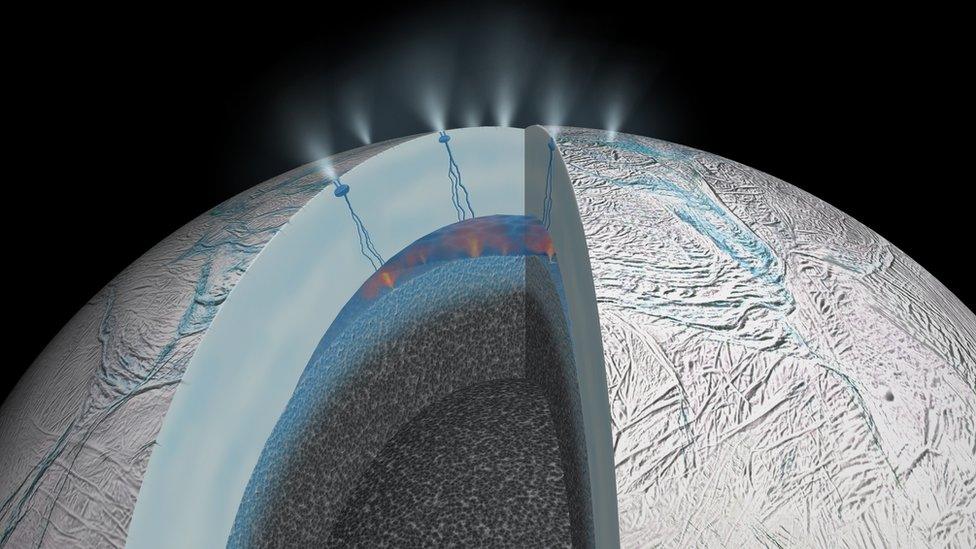

Scientists say it has an ocean beneath its icy crust.

What is more, the conditions in this global body of liquid water could be benign enough to support microbial organisms.

"Enceladus is not just an ocean world - it's a world that might provide a habitable environment for life as we know it," said Cassini program scientist Curt Niebur, in a media briefing on Monday.

"On Wednesday we'll plunge deeper into that magnificent plume coming from the South Pole than ever before. And we will collect the best sample ever from an ocean beyond earth."

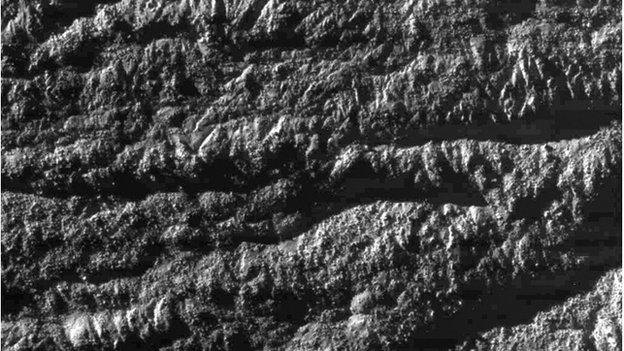

Streams of water flow into space from dramatic "tiger stripes" near the moon's southern pole

Cassini will attempt to detect molecular hydrogen during Wednesday's encounter.

This would be a strong signal that hot vents exist on the rocky ocean floor.

If that is the case, it would be another plus-point in the moon's habitability potential.

Such vent systems are known on Earth to provide the fundamental energy and nutrient requirements for some deep-sea ecosystems.

At these locations, water is drawn into the rock bed, heated and saturated with minerals, before then being ejected back upwards.

Bacteria thrive in this environment, establishing a food web that supports a chain to more complex organisms.

Whether any of this is going on inside Enceladus is just speculation for now.

This is what the "tiger stripes" look like up close

"The amount of hydrogen emission will reveal for us how much hydrothermal activity is actually occurring on that seafloor - with implications for the amount of energy available," said Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker, from Nasa's Jet Propulstion Laboratory in California.

The flyby took place at about 10:00 Pacific time (17:00 GMT) on Wednesday - but the anticipated scientific insights may be days or weeks away.

"We will have a first chance to have a look at the gas and particle data within about a week of the flyby - a first, quick look. Then over the coming weeks we'll do a more detailed analysis, to really help us understand what's going on in that tantalising ocean on Enceladus," Dr Spilker said.

Final chapter

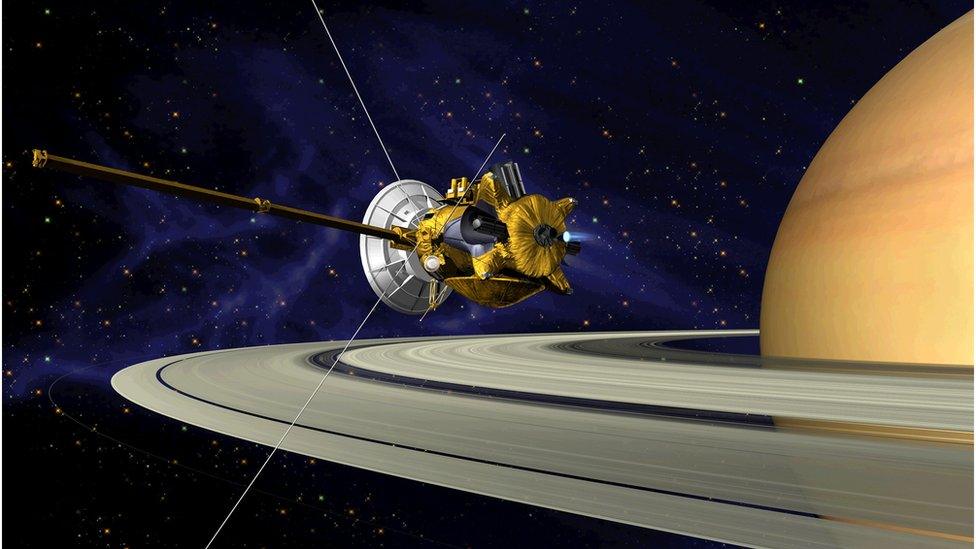

Cassini is entering the end stages of its mission to the Saturnian system, which began with an insertion into orbit around the ringed planet in July 2004.

Since then it has made repeated passes of the major moons, to image them and to characterise their make-up and environment.

Scientists think Saturn's gravity squeezes Enceldus, heating its interior

This latest visit to Enceladus is one of the very closest. Indeed, Cassini will never again get quite so near to the moon's surface.

In December, it will venture to within 5,000km of the wrinkled terrain, but thereafter it will fly no closer than 22,000km.

As a consequence, Wednesday's rendezvous represents the last real opportunity to sample the densest regions of the jets.

Previous detections by the probe's instruments have already identified salts and organics in the icy spray.

Key indicators of hidden vent activity include the presence in the plumes of silica particles and methane.

Molecular hydrogen would be a key find: an "independent line of evidence" for hydrothermal activity, according to Dr Spilker. It would support the notion that a process known as serpentinization was in play.

This sees rocks rich in iron and magnesium minerals react with water, and incorporate H2O molecules into their crystal structure.

On Earth, some micro-organisms are able to use the hydrogen byproduct from serpentinization as an energy source to drive their metabolism.

Cassini will end its days with a plunge into Saturn's atmosphere

Next year, Cassini will begin a series of manoeuvres to put itself in orbits that take it high above, and through, Saturn's rings.

Then, in 2017, once the probe's fuel has all but run out, ground controllers will command the spacecraft to plunge into the planet's atmosphere, where it will be destroyed.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 October 2015

- Published16 September 2015

- Published3 April 2014

- Published31 July 2013