Enceladus: Does this moon hold a second genesis of life?

- Published

- comments

The Enceladus Interplanetary Geyser Park: Might we go there someday?

The mighty Cassini probe has made many great discoveries at Saturn, but none top its extraordinary revelations at Enceladus.

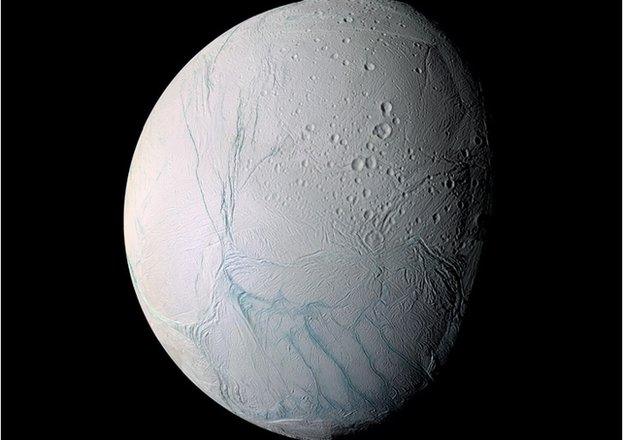

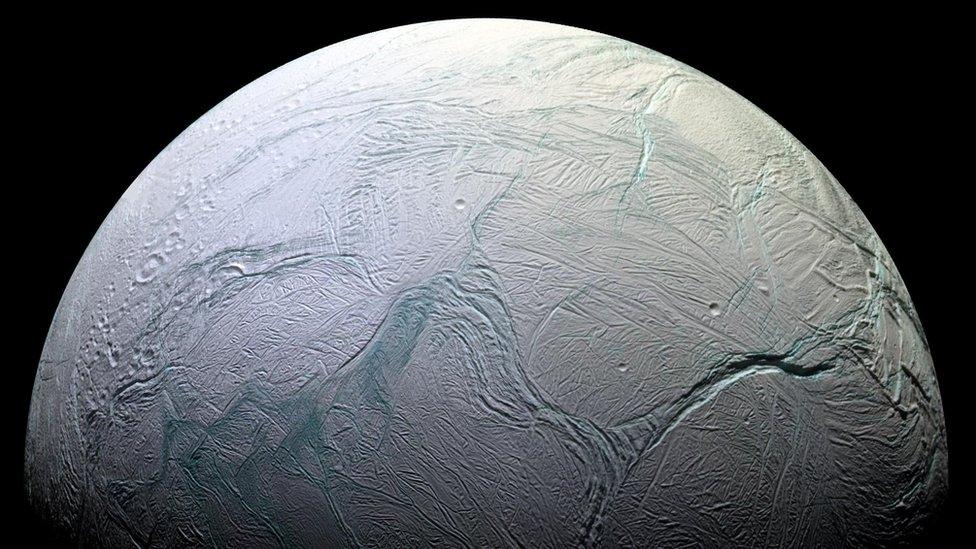

What the plutonium-powered satellite has seen at this 500km-wide, ice-crusted moon is simply astounding.

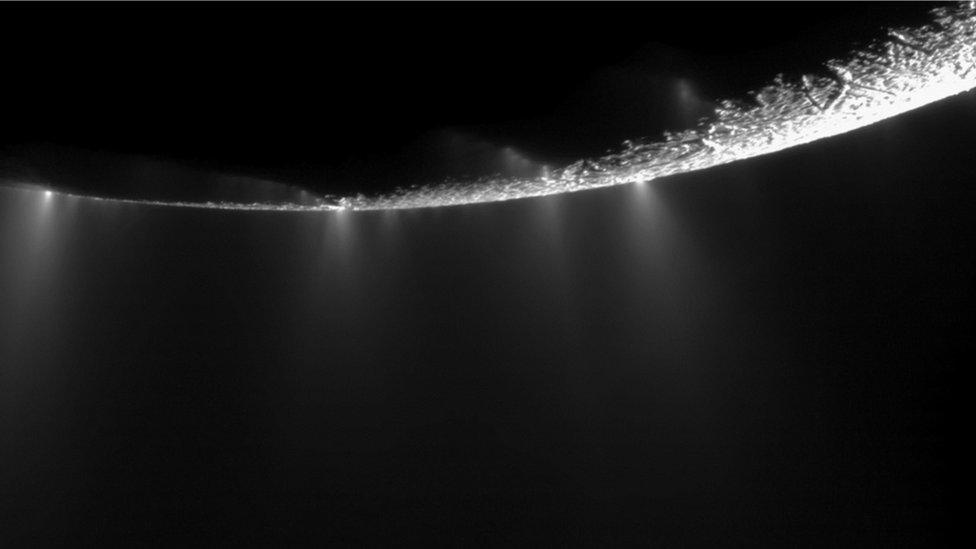

Cassini has pictured huge jets of water vapour and other materials spewing from cracks at its south pole.

It's quite a spectacle, and it's unique in the Solar System, according to Carolyn Porco, who runs the camera system on the big spacecraft.

"It became a joke on our team that we had found the Enceladus Interplanetary Geyser Park, and that future generations may go there just for vacation," she tells me in a Discovery programme all about Enceladus which goes out on the BBC World Service on Monday.

But researchers are not laughing when they say this little world is among the best places to search for life beyond Earth.

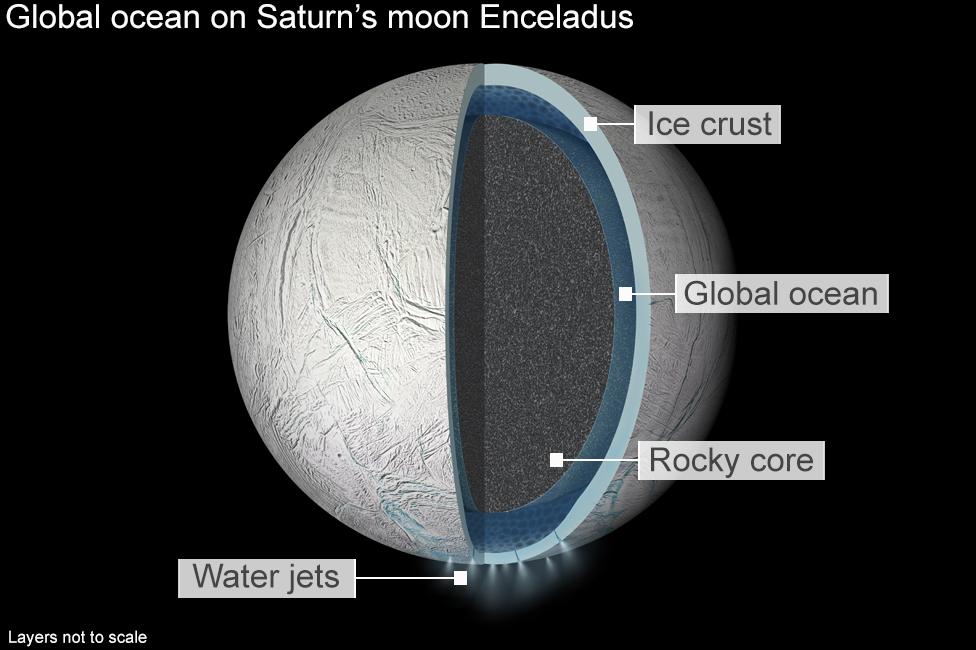

The plumbing for the jets leads to a vast body of water that may be 30-40km deep in places. And Cassini's instruments have been able to show, by flying through and sampling the emissions, that the conditions and - importantly - the chemistry in this subterranean ocean could support microbial life.

There are strong indications that the water is interacting with rock at the ocean bed, to produce the sort of nutrient cocktail on which simple bugs could dine.

Chris McKay is an astrobiologist with Nasa: "I've been interested in the search for life in the Solar System for decades and I'm still flabbergasted by what we're seeing on Enceladus. It's such a small world so far from Earth, putting out such a wealth of organics and water and indications of habitability - it's astounding, and the samples are right there, free for the taking."

But as capable as Cassini is, its 1980s/90s technology cannot definitely prove the case for microbes under the icy surface of Enceladus.

For that we'd need a different kind of satellite with specialised sensors.

Cassini will make one final close flyby of the moon next week to acquire a last batch of detailed surface pictures.

It will then move across the Saturnian system to prepare for some end-of-mission observations of the ringed planet itself.

So, we're about to bid farewell to Enceladus, and of course that's prompted people to start talking up how we might return one day with far more capable instrumentation.

Jonathan Lunine is an interdisciplinary scientist on the Cassini mission at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. He has a concept for a future spacecraft he calls the Enceladus Life Finder (ELF).

This would be a smaller probe than the goliath currently orbiting Saturn, but what it would give up in size (and cost) it would more than compensate for with sophistication.

Its instruments would be dedicated to the very specific job of analysing the contents of the jets for any chemistry associated with biology.

"With very powerful mass spectrometers, we would be able to detect amino acids and identify them," he says.

"We would be able to detect fatty acids found in the membranes of bacterial cells; and their cousins, the so-called isoprenoids, which are in the membranes of the cells of archaea, those microbes that exist in extreme environments on the Earth.

"We'd also be able to count their carbon numbers to see if they've got the pattern of life. And then finally we'd be able to measure the isotopes for all the carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, to see whether the chemistry is like that which occurs on Earth, where organisms prefer the lighter isotopes as they process this material through their systems."

The ELF concept was submitted to a recent Nasa competition to find a future planetary mission, but was not selected. One of the issues for any kind of venture like this is the availability of energy so far from the Sun (the distance to the Saturnian system is 1.4 billion km).

Cassini relies on its "nuclear battery" for all its electrical needs. Such power units are expensive and currently in very short supply.

One could go with solar panels but it would be challenging: the strength of the sunlight near Enceladus is about a hundredth of what it is at Earth.

Jonathan Lunine describes how you would detect simple life at Enceladus

Nonetheless, the case to go back to the bright white moon of Saturn is so compelling that a way will surely be found, because not only is Enceladus one of the best places to search for extra-terrestrial life - it is also the easiest. Unlike on Mars, or on Europa (Jupiter's bigger version of Enceladus), there is no requirement to land and drill to gather samples for analysis. At Enceladus, those samples are continually being pumped into space via the south polar jets.

Peter Tsou calls them "low-flying fruit" and he has a concept for bringing them back to Earth for even more detailed assessment in the world's best-equipped laboratories.

His Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE) mission would look a little like Nasa's Stardust endeavour, which returned particles in 2006 from the vicinity of a comet.

Tsou used an array of silicon dioxide foam, called aerogel, to snatch the samples as the Stardust probe flew through the ice object's gas and dust shroud.

"With Stardust, I flew aerogel in 2x4x3cm cubes. I had 132 of them. I discovered that, wow, even with one or two cubes, it was more than enough to go around," he recalls.

"So, no, we do not need a lot. However, the challenge is that because the samples are small and we're talking about life, any Earth contamination will ruin the samples, because then we'd find, 'Oh yeah! It's like my saliva!'. We'd have to be very meticulous to separate [the samples] from Earth contamination."

Peter Tsou has helped develop techniques to capture samples and bring them back to Earth

Tsou reckons a sample-return mission to Enceladus could take 14 years, from launch to having some moon material in an Earth lab.

"If we discover life on a place like Enceladus it's obviously going to be something simple like microbial life," observes Porco.

"Of course, if we discovered lobsters that would be fascinating; who knows? Maybe," she chortles. "But we're setting our sights on something simple; just evidence for microbial life.

"That would be a paradigm shift. What kind of life is out there? Is it like Earth life; is it not? Is it based on DNA; is it not? It would be a major discovery, probably the greatest scientific discovery we could make. We have to go back."

And Lunine's wider perspective is this: "This is a place that we can go [to] where, if we find the signs of life, we can be very, very sure it's life that had a second origin.

"But it will also allow us, I think, to turn attention to the galaxy beyond, and realise that if life can start twice, or three times or four times in our own Solar System - how many habitable planets in the galaxy must have life today?"

Enceladus: A second genesis of life? is broadcast on Monday 14 December, as part of "Space Week" on the BBC World Service. The programme is presented by Jonathan Amos and produced by Andrew Luck-Baker.

The broad cracks, or "Tiger Stripes", at the southern pole are the source of the jets

- Published28 October 2015

- Published22 October 2015

- Published16 September 2015

- Published3 April 2014

- Published31 July 2013