Bloodhound Diary: It's rocket science

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle will first mount an assault on the world land speed record (763mph; 1,228km/h). Bloodhound, external will be run on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa, in 2016.

Wing Commander Andy Green, the current world land-speed record holder, is writing a diary for BBC News about his experiences working on the Bloodhound project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

I'm regularly asked whether Project Bloodhound is going to develop any new technology that will be used in the future.

My answer is always "I hope not". Bloodhound is not aiming to develop new engineering; we are aiming to develop new engineers.

New technology is difficult and expensive to produce, and we have to assume that it's unreliable until it's been properly tested and developed.

Proven "off the shelf" technology is always a better choice, especially for a small fast-moving (!) project like a Land Speed Record.

Bloodhound is using existing technology in new ways, in order to bring science and technology to life for the next generation of engineers.

Solids and liquids - not for us

However, that's not quite true for Bloodhound's rocket programme.

The education/inspiration role is still the essential part of what we do, including for the rocket programme, but I'll come back to that later.

The problem with the rocket programme is that we do appear to be in the "developing future technology" business, whether we like it or not.

The good news is that we seem to be rather good at it.

Frist, a brief summary of why we're developing a rocket.

We need some form of rocket system in order to reach 1000+ mph, as jet engines alone won't be enough - after all, we're trying to go faster than any jet fighter has ever been at ground level, so we're above the design speed of any known jet engine.

Hence, we need a rocket, but what type?

Solid rockets (like very large fireworks) can't easily be controlled or shut down, so they are not a favourite of mine.

Liquid rockets (the sort used for "normal" space rocket launches) work by mixing two very excitable liquids together and trying to control the very angry reaction it causes.

Liquid rockets are very powerful, but the liquids are not nice to use (or to carry in large quantities in the car with me) so once again this is not ideal.

Hence our choice was for a hybrid rocket system.

The Nammo Hybrid rocket - Bloodhound's choice

The solid fuel "grain" (basically a long tube with a hole down the centre) is made from a synthetic rubber called HTPB, while concentrated hydrogen peroxide, known as "high-test" peroxide (or HTP for short) gives us a fairly well-behaved oxidiser. These make for a safe payload in rocketry terms.

The rubber fuel is, well, just rubber.

In dilute form, hydrogen peroxide can be used for a number of things including hair bleach - hence the term "peroxide blonde" - and as long as the concentrated HTP is kept cool and clean, it also behaves itself nicely.

These chemicals are certainly a whole lot more friendly than liquid hydrogen, liquid oxygen, various solid fuel "explosives", etc., that other rockets use.

The tricky bit in a hybrid rocket is pumping the HTP oxidiser into the fuel grain at high pressure and then managing the burning process (known as "regression") of the rubber fuel grain, once the hybrid reaction (very high temperature burning rubber) starts to generate the thrust.

This is the system that the Bloodhound team has been developing, in conjunction with our rocket partner Nammo.

Making the world's best pump

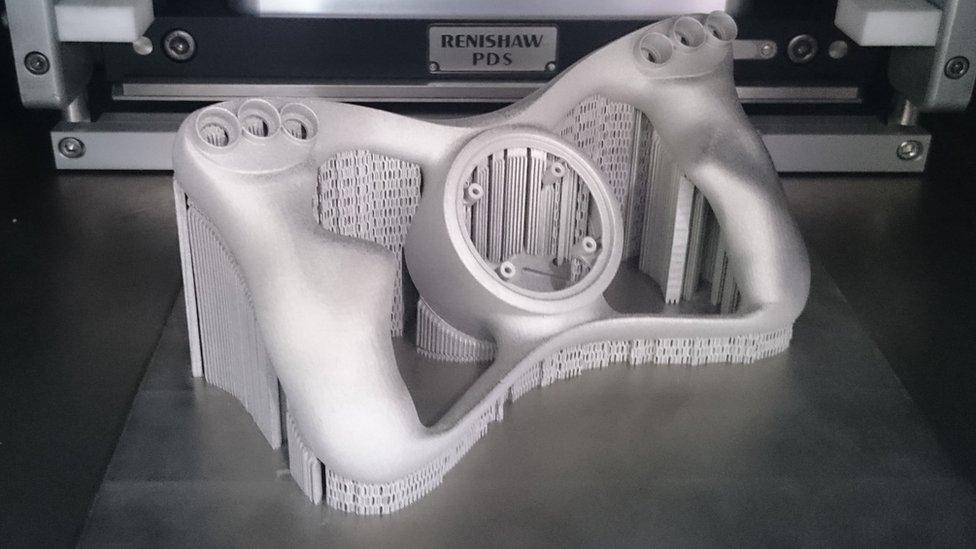

Bloodhound's rocket pump, external has been produced in-house.

Starting with a 1960s design from the British rocket programme (which also used HTP all those years ago), we've used modern computer modelling and specialist manufacturing processes to produce the most efficient HTP pump ever made.

The pump still needs over 500hp to drive 800 litres (approximately one tonne) of HTP, at 75 Bar (1,100psi), into the rocket in just 20 seconds, which is why we've got Jaguar's 5 litre supercharged V8 engine as a pump motor.

Add a whole series of valves, electronic sensors and computer controls, plus flushing and purging systems, and you've got a complicated (but safe) rocket system (summarised in this rocket animation video, external, which is worth watching just for the Elbow soundtrack).

The Bloodhound team delivered its first full-scale firing back in 2012, external, working with the Falcon Project to test our first prototype.

With that background knowledge, we then made some big changes to the design, using several smaller rockets as an alternative to one large one.

First hybrid firing

Two years later, Nammo fired the first of the revised rocket designs, external intended for use in the car.

Two years might sound like a long time, but for rocket development, that's virtually overnight.

This rapid-prototyping approach is grabbing people's attention in the rocket world. We're using some components (like the Jaguar V8) that are too heavy for a flight system like a space rocket, but Bloodhound's approach is getting things done quickly and cheaply - just what a Land Speed Record team needs.

Quick and effective

So much for the rocket system in the car. If you add in the requirement to set a World Land Speed Record, then things get even more difficult.

We'll be operating the rocket out in the middle of a desert, not in a specialist rocket facility, so we'll need a lot of support equipment for servicing, fuelling, HTP storage and so on.

The FIA regulations, external require the car to do two runs, in opposite directions, within one hour.

Instead of days to prepare the rocket for another firing, we've got to replace the fuel grain, reload a tonne of HTP, replace the car's coolant, reset all the systems, and get all that done in about 30-40 min.

This is a classic blend of aerospace and motorsport technologies: a racing pit stop for a hybrid rocket.

To deliver this race-capable rocket system in the desert, we are preparing some specialist support vehicles and equipment.

These are being delivered in the same short period of time.

I've only just found out that this support equipment is regarded as so innovative that one of our rocket support team is writing his post-graduate thesis on its development.

Like it or not, we really are developing new technologies and new ways of doing things.

Bloodhound's use of HTP is also generating a lot of interest.

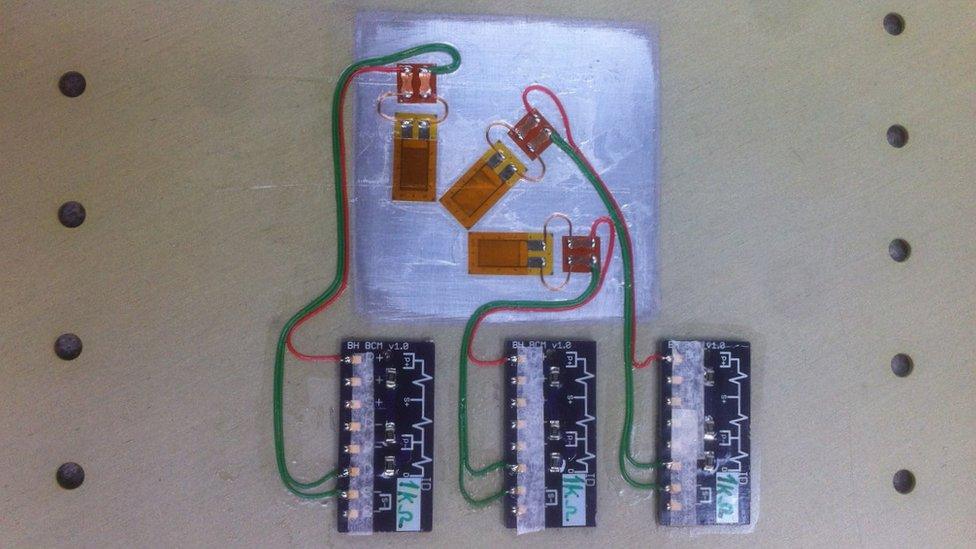

We've set up our own test laboratory to check that all the key materials in the car are HTP compatible.

That includes the Alpinestars fire-proof overalls, boots, gloves etc, that I'll be wearing to drive Bloodhound (the suit was absolutely fine, by the way, but the boots needed a bit of modification - the leather bits were reactive).

They even tested my flame-resistant underwear!

Alpinestars uses a natural fibre called "Lenzing FR", made from trees (yes, I know that sounds wrong, but apparently my underwear really is made with Beechwood fibres).

I was sure that anything from a tree would react furiously with HTP.

Shows how much I know: the flame-proof "wooden" underwear is also very HTP-resistant.

Sadly, this robs me of the chance to say "that run was so fast that my underwear nearly caught fire", as the team now knows that this can't happen.

HTP is also a very "green" fuel.

It's non-toxic, relatively easy to store and use, and produces the cleanest decomposition products imaginable - water and oxygen.

Challenging schools everywhere

We've been approached by a range of people, from the space industry to universities, seeking advice on using it.

I don't know if HTP is going to find its way into everyday vehicles any time soon (storage and handling does require some care), but it's a really interesting option for an alternative fuel source - so who knows?

We are trying to avoid using too much "new" technology for Bloodhound, but as you can see, we do have to develop some to get us to 1,000mph.

The new technology does come with one big advantage - as Bloodhound is an "Engineering Adventure" designed to bring technology to life, it gives us an even better story to tell.

As well as developing our own rocket technology on the car, we're seeing more and more schools taking part in the Bloodhound Model Rocket Car Challenge, external.

Ever fancied getting your name into the Guinness Book of World Records? Here's one exciting way to do it.

Don't wait too long, though; the competition is getting more intense every day.

Jas with our newest Bloodhound Ambassador

Interest in the Model Rocket Car Challenge goes much wider than just UK schools. Over the week of the Brazilian Grand Prix, we had a small team out in Sao Paolo, helping the UK Government to promote the very best of British innovation and technology (Project Bloodhound!).

We were also there to support Brazil's huge interest in the Rocket Car Challenge, which is going country-wide in Brazil.

The teams from the SENAI academy seemed to get the hang of it really quickly - subject to ratification, they have already set a world record in the 50-metre category. Well done them!

Another great result in Brazil was signing up our newest Bloodhound Ambassador, the Brazilian F1 racing legend Emerson Fittipaldi, who was recruited by our Rocket Challenge manager, Jas Thandi.

Having this level of support for the Brazilian education campaign will make a big difference. Thank you, Emerson.

As a final thought, the Bloodhound rocket programme has forced us to change the way we talk about things.

We can't use the phrase "it's not rocket science" anymore, because Bloodhound is the ultimate Engineering Adventure. It really is rocket science.

- Published16 November 2015

- Published24 September 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published25 July 2015

- Published7 July 2015

- Published12 June 2015

- Published10 June 2015