Cryosat captures Greenland's shifting shape

- Published

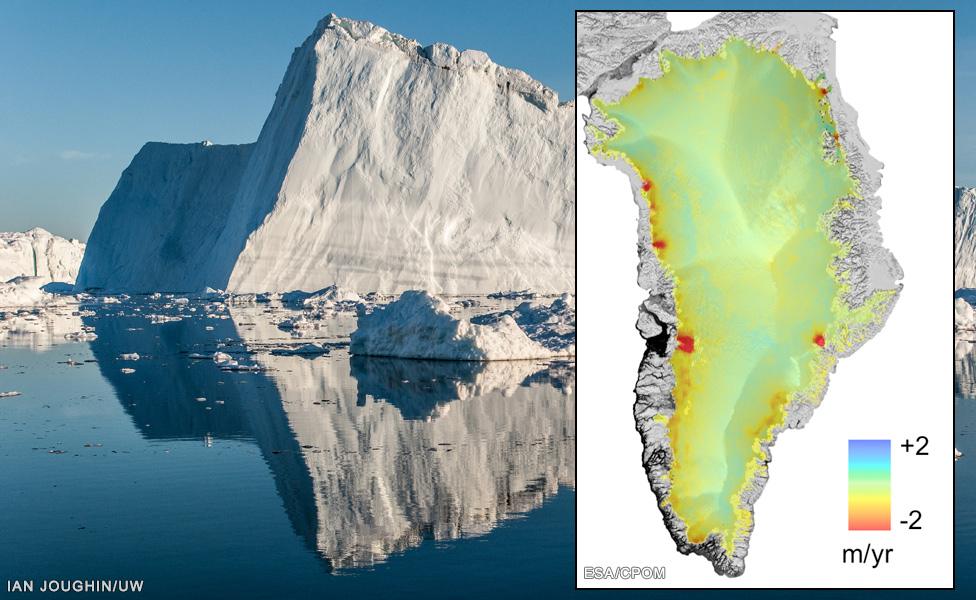

The Cryosat data makes it easier to monitor big coastal glaciers like Jakobshavn

It is one of the clearest views we have yet had of the recent changes occurring across Greenland's ice sheet.

Scientists using Europe's Cryosat radar spacecraft are now routinely mapping variations in height on a fine scale, both in time and in area.

The UK-led team's analysis shows that Greenland is shedding ice to the ocean.

Their preliminary assessment is very close to that produced from gravity satellites, which currently see losses of over 250bn tonnes of ice each year.

But while the headline numbers may be similar, Cryosat brings important additional detail to the picture.

It allows the team to study changes across the entire ice sheet at fine resolution, meaning the scientists are able to monitor the behaviour of individual glaciers.

Cryosat is also helping them to track seasonal variations in the elevation of the ice sheet, which will permit the researchers to investigate how the ice sheet changes from year to year.

"These results allow us to identify key glaciers which, in the last few years, are showing signs of rapid change," said Dr Malcolm McMillan from the NERC Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM), external at Leeds University.

The new study updates a previous assessment by the Alfred Wegener Institute, and complements existing measurements made by the US space agency's GRACE gravity satellites. These are spacecraft that can essentially "weigh" the ice sheet from orbit.

Dr McMillan and colleagues are presenting their work this week in San Francisco at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the largest annual gathering of Earth scientists.

Prof Andy Shepherd explains the changes seen by CryoSat since 2010

Researchers have previously used space- and plane-borne laser altimeters to produce the kind of maps now coming from Cryosat.

But their data was often very sparse, making it difficult to achieve a comprehensive and up-to-date picture.

The earlier radar missions, too, struggled to get to grips with Greenland.

In part, this was because their measurement footprints were too large to really see even the biggest glaciers, but also because they were sometimes frustrated by surface conditions.

"Radar altimeters bounce their signals off a horizon that is below the top of the snow, where the ice becomes compacted," explained Leeds co-worker Prof Andy Shepherd.

"But if there is a big melt, as we saw in the middle of Greenland in 2012, the snowpack conditions change and this scattering horizon is re-set, making it appear as if the ice sheet has gained one to two metres in height.

"With these new results, we have been able to correct for this, and that allows us to confidently map changes in elevation."

Artist's impression: Cryosat, with its radar altimeter, was launched into orbit in 2010

The CPOM study means Cryosat has now produced a "report card" on all three of the polar ice domains it was tasked by the European Space Agency to investigate.

A similar assessment has been done for Antarctica, and the spacecraft is also now consistently monitoring the thickness of Arctic sea-ice, its primary mission goal.

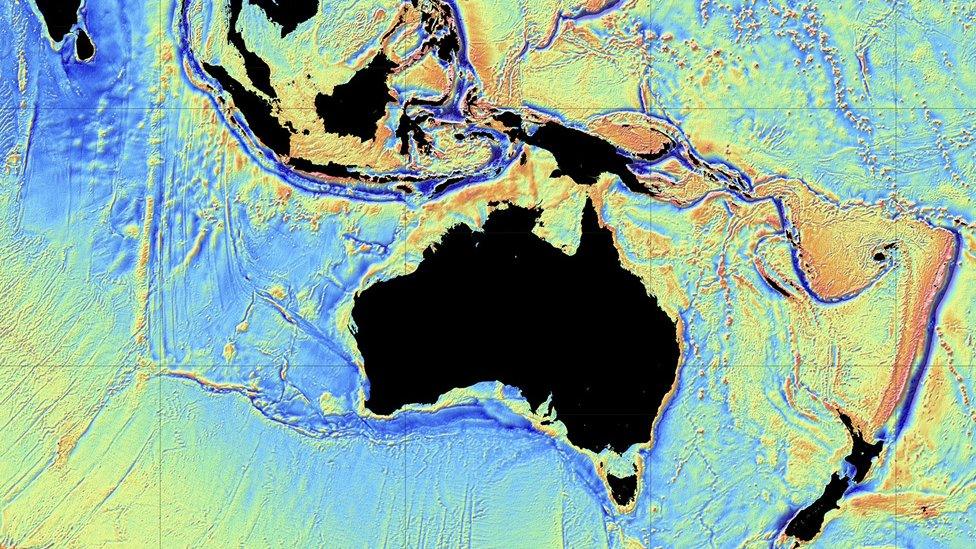

In addition, as a secondary objective, the Esa spacecraft's radar has managed to make the most precise map of the shape of the global ocean floor.

Cryosat has now fulfilled the key objectives it was set by the European Space Agency

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published26 October 2015

- Published19 May 2014

- Published2 October 2014