Ground control bids farewell to Philae comet lander

- Published

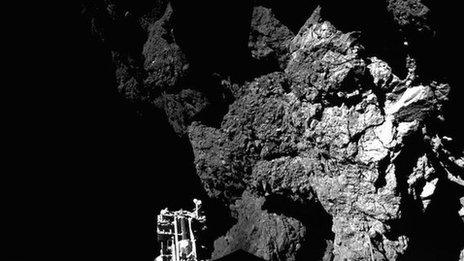

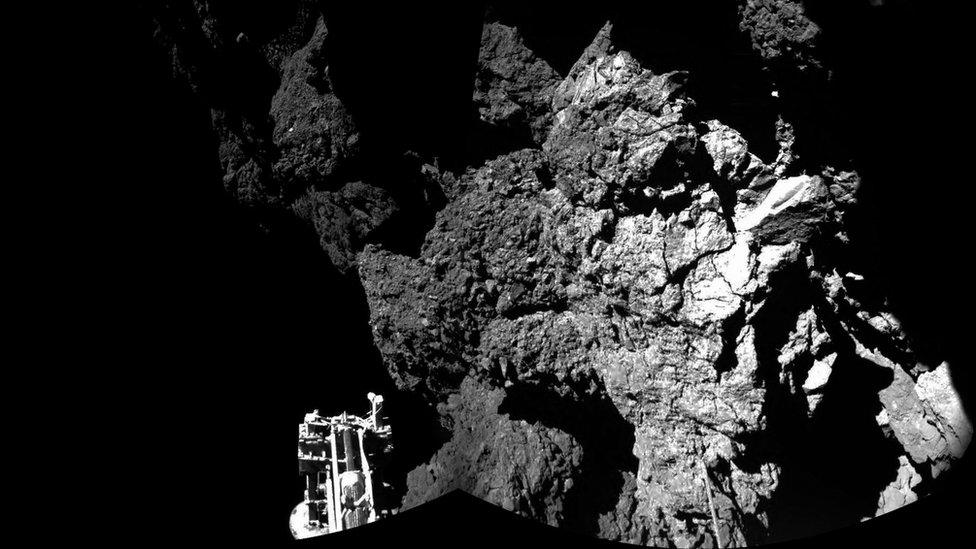

Philae sent back the first ever photos from the surface of a comet

Mission scientists have decided to give up trying to contact the comet lander Philae.

The European Space Agency's Rosetta mission dropped the robot onto Comet 67P in November 2014.

But after a troubled landing and 60 hours of operation, there has largely been radio silence from Philae.

The German Aerospace Center (DLR), which led the consortium behind Philae, said the lander is probably now covered in dust and too cold to function.

"Unfortunately, the probability of Philae re-establishing contact with our team at the DLR Lander Control Center is almost zero, and we will no longer be sending any commands," said Stephan Ulamec, the lander's project manager at DLR.

The probe's historic landing famously happened several times in succession - with its first bounce looping nearly 1km back from the comet's surface and lasting a remarkable 110 minutes.

When it finally settled, its precise location was unknown but images and other data suggested it was sitting at an awkward angle, in the shade.

This sped-up animation shows the estimated trajectory of Philae's bumpy landing

That meant Philae's scientific activities were limited to a single charge of its solar-powered batteries.

On several occasions, attempts to contact Philae - via the Rosetta spacecraft, still orbiting Comet 67P - did receive a response.

But the last such contact was on July 9 2015 and the comet is now hurtling into the much colder part of its orbit, plunging to temperatures below -180C at which the lander was never designed to operate.

"It would be very surprising if we received a signal now," Dr Ulamec said.

RIP little robot: Jonathan Amos, BBC science correspondent

While there is always hope, there is also the reality of the frigid conditions of outer space.

Ultra-low temperatures in the shade on Comet 67P have likely buckled and snapped some of Philae's components. While many of the lander's parts were designed for this harsh environment, there were certain electronics kept in a "warm box" that have now unquestionably been pushed beyond their "qualified" limits - including the onboard computer and the communications unit.

We can't know for sure why Philae stopped its intermittent calls home. It could be covered in dust; it could have been bumped by a jet of gas into a new position that obstructs its antenna. But the chances that we will hear from it again appear less than slim.

It would be great to get a celebration picture of it on the surface, taken from the Rosetta mothership as it moves in closer to the comet this year. But this again seems a longshot. Rosetta has imaged the little robot's presumed position before from inside a distance of 20km and seen nothing convincing.

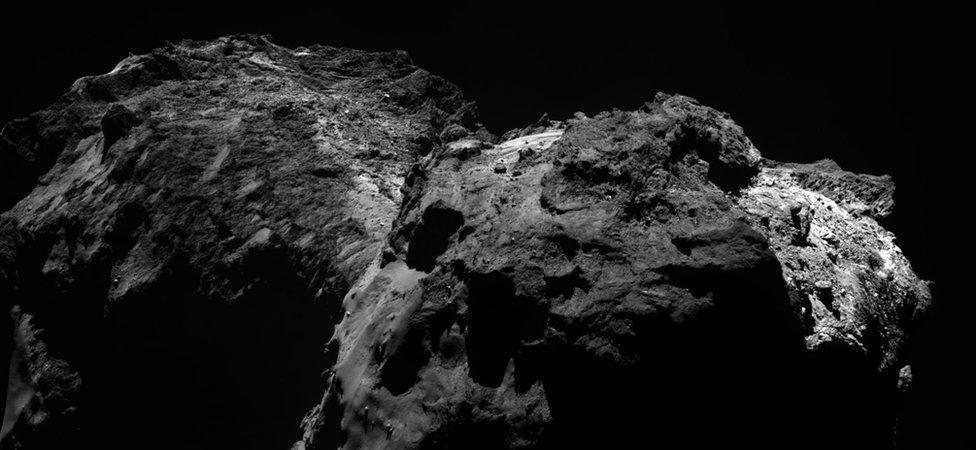

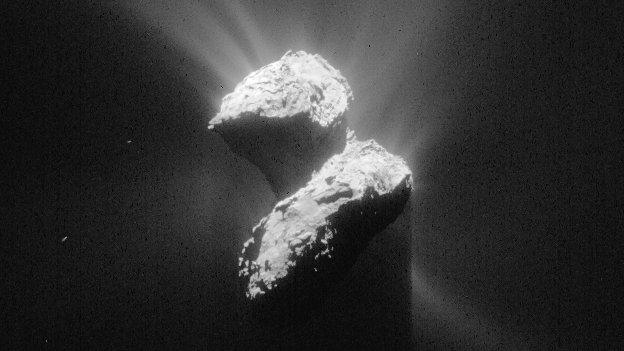

Philae's home: Comet 67P

To go even closer, for better resolution images, takes the probe into a region where the lumpy gravitational field of the irregular-shaped comet becomes hard to navigate. And that is a risk controllers really don't need to take.

Rosetta and its ongoing science observations at 67P really are the priority. The very best of this science may be acquired in September when the spacecraft spirals down to try to make its own "landing" on the comet.

The finesse with which the European Space Agency team in Darmstadt, Germany, is able to fly Rosetta promises to make this event just as thrilling as the descent of Philae back in November 2014.

Speaking to BBC Radio 5 Live, the European Space Agency's senior science advisor Mark McCaughrean said today's news was sad but inevitable.

"It's a sad day, of course. Philae certainly captured the imagination around the world back in 2014.

"But all good things come to an end. In fact, if it had landed properly on the surface in the first place, it all would have been over last March because Philae would have overheated."

Prof McCaughrean emphasised that the Rosetta orbiter was "still out there doing fantastic science".

- Published19 June 2015

- Published14 June 2015

- Published13 November 2014