Banksy lawyers delayed geographical profiling study

- Published

Banksy's works are concentrated in London and Bristol

A study that tests the method of geographical profiling on Banksy has appeared, after a delay caused by an intervention from the artist's lawyers.

Scientists at Queen Mary University of London found that the distribution of Banksy's famous graffiti supported a previously suggested real identity.

The study, external was due to appear in the Journal of Spatial Science a week ago.

The BBC understands that Banksy's legal team contacted QMUL staff with concerns about how the study was to be promoted.

Those concerns apparently centred on the wording of a press release, which has now been withdrawn.

Taylor and Francis, which publishes the journal, said that the research paper itself had not been questioned. It appeared online on Thursday unchanged, after being placed "on hold" while conversations between lawyers took place.

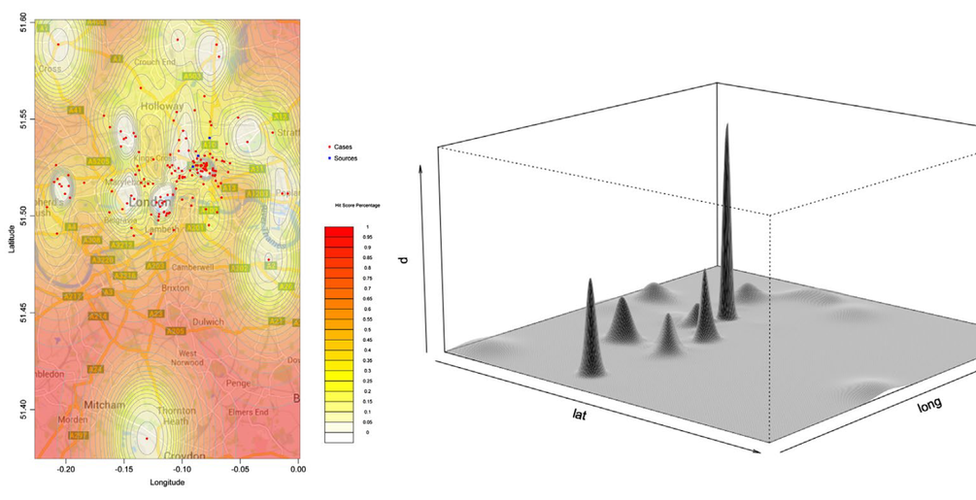

Geographic profiling is a statistical technique that originated in criminology but has recently proved its value in other fields, from tracing infectious disease outbreaks to locating the roosts of wild bats.

It takes a large set of locations - whether crime scenes, disease cases or bat feeding sites - and runs through various groupings of those locations to find "hot spots" that could be jumping-off points for whatever activity is being mapped.

The hot spots can be used to concentrate a subsequent search, or to whittle down a long list of suspects.

When the QMUL researchers put the method to work on a list of Banksy artwork locations in London and Bristol, they said that the resulting "geoprofile" was a good match for an obvious candidate: Robin Gunningham, whom the Mail on Sunday named in 2008, external after an investigation into Banksy's identity.

A geographic profile, calculated across London, showed peaks in particular locations

Addresses connected to Mr Gunningham using publicly available information - places he has lived or frequented, for example - scored highly on the geoprofile in both cities.

The scientists conducted the study to demonstrate the wide applicability of geoprofiling - but also out of interest, said biologist Steve Le Comber, "to see whether it would work".

"What I thought I would do is pull out the 10 most likely suspects, evaluate all of them and not name any… But it rapidly became apparent that there is only one serious suspect, and everyone knows who it is.

"If you Google Banksy and Gunningham you get something like 43,500 hits."

In January, a satirical work near the French embassy in London was boarded up

He and his colleagues are fans of the artist, Dr Le Comber said, and did not believe their work had "unmasked" him.

"I'd be surprised if it's not [Gunningham], even without our analysis, but it's interesting that the analysis offers additional support for it.

"You sort of default to the terminology from criminology, where you're talking about suspects and crime sites, but that doesn't imply any moral judgment - that these are actually crimes, or to be deplored, or whatever.

"That's even more important in disease biology, of course."

The criminologist and former detective who pioneered geoprofiling, Canadian Dr Kim Rossmo - now at Texas State University in the US - is a co-author on the paper.

The researchers say their findings support the use of such profiling in counter-terrorism, based on the idea that minor "terrorism-related acts" - like graffiti - could help locate bases before more serious incidents unfold.

Banksy has also staged more formal exhibitions, like the recent Dismaland 'bemusement park'

Commenting on the research, Spencer Chainey from University College London said it was an intriguing and "perfectly legitimate" application of the technique.

"I'd never thought of it being used that way," said Dr Chainey, who runs the only geographic profiling course held outside the US.

He added that the study is perhaps not as precise, in some respects, as the way working criminologists might use the method. Outliers in the location data were not excluded, for example, and the researchers did not use a timeline of which graffiti appeared when.

"They've looked at all the data without considering the temporal features of it. I don't necessarily think they haven't got the right man - I just think there's more they could have done to fine tune the analysis."

Banksy draws many tourists to Bristol, eager to visit the numerous sites where he has left his mark

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published25 January 2016

- Published11 December 2015

- Published20 August 2015

- Published27 May 2015

- Published5 May 2015

- Published28 April 2014

- Published14 April 2014

- Published9 October 2013