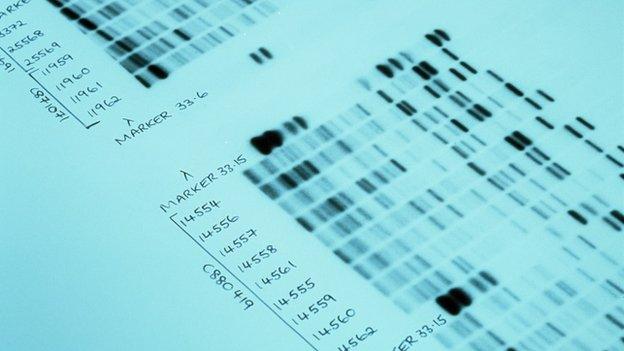

Can we still rely on DNA sampling to crack crime?

- Published

- comments

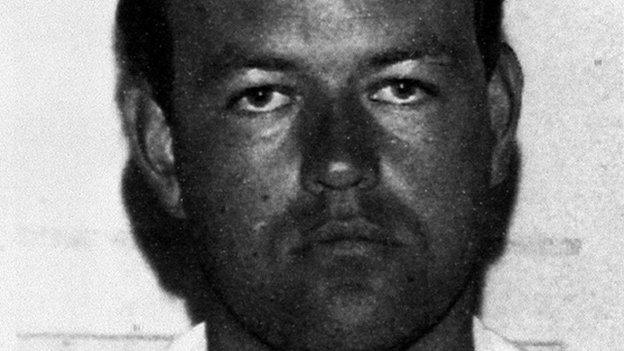

Last month, a compelling TV programme revisited the case of Colin Pitchfork - the first person to be convicted because of DNA evidence.

In 1988, Pitchfork admitted raping and murdering two 15-year-old girls, Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth, after his DNA matched samples found at the scene of both crimes.

The former baker was caught after the world's first mass screening, external for DNA, in which 5,000 men in three villages in Leicestershire were asked to volunteer blood or saliva samples; he'd initially evaded capture by getting a friend to take the test for him.

As Pitchfork approaches the end of his 28-year minimum jail term, the ITV drama-documentary, Code of a Killer, was a timely reminder of the debt we owe to the inventor of DNA profiling, Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys, and Detective Chief Superintendent David Baker, the investigating officer who had the determination and courage to ensure the technique was applied in the case.

Now, of course, DNA evidence is almost taken for granted.

DNA database:

Since 1995, the genetic information from DNA samples taken by police across the UK has been added to a database, which has grown to contain the profiles of 5.7 million people (though some profiles are duplicates).

The database also holds 450,000 DNA profiles from crime scenes.

The Home Office, which runs the database on behalf of the police, says over 13 years until March 2014, it produced 471,000 matches between suspects and crimes.

In one three-month period alone, between April and June last year, there were 37 matches to murders and 127 to offences of rape.

Too complex

But over the past two years the operation of the database, and the techniques underpinning it, have altered dramatically in a way that is only just beginning to be understood.

In 2013, as part of the Protection of Freedoms Act, external, the database was pruned in order to remove the details of innocent people - 1.7 million profiles of children and of adults who hadn't been convicted of any crime were deleted.

Prof Alec Jeffreys invented DNA profiling

That Act was the result of a battle by civil liberty campaigners and others after the European Court of Human Rights ruled in 2008 that the then UK Government's "blanket and indiscriminate" policy of storing DNA profiles indefinitely failed to strike "a fair balance" between an individual's right to privacy and the state's interest in tackling crime.

Under the Act, a complicated system of retention rules was introduced to differentiate between adults and those under 18; between people who have been cautioned or convicted and those who haven't; and between low-level offences and crimes such as burglary, rape, murder and terrorism.

The new arrangements are so convoluted that even the man responsible for overseeing them, Alastair MacGregor, the Biometrics Commissioner, has cast doubt as to whether they can work effectively and fairly.

In a little-publicised report, external in December 2014, Mr MacGregor says compliance with the regime, by programming the Police National Computer so that DNA profiles are retained and deleted as they should be, is "an impossible task".

Samples mishandled

He says "thousands of profiles" that should have been deleted are retained on the database and about 30 have been inadvertently removed.

Kerri Allen, a DNA specialist who used to work for the Forensic Science Service, is also concerned about the new system.

"It's immensely complicated," she says. "The administration involved in removing a profile is far greater than you might imagine.

Colin Pitchfork was convicted because of DNA evidence

"I don't know if it's workable."

Of course, it may take time for the new procedures to bed in: there were always likely to be bumps on the road.

But Mr MacGregor has further concerns - about the use of DNA profiles from foreign offenders.

It seems that various legislative hurdles are blocking police forces from holding profiles from foreign nationals known to have committed offences overseas, a problem that may also affect some offenders convicted in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

It's an "unsatisfactory state of affairs," he writes, "which might well be putting the UK public at unnecessary risk."

The new Home Secretary, whoever it is after 7 May, will surely take note.

Developing science

The other key development is the scientific method now used to obtain DNA profiles.

It is known as DNA 17, external, because it looks at 17 areas of a person's DNA.

Will sampling pick up the right DNA?

In July 2014, it replaced the previous technique, SGM+, which examined 11 areas, bringing England and Wales in line with other European countries, though Scotland is already now moving to an advanced version - DNA 24.

DNA 17 is a more sensitive test than its predecessor, which means it is possible to produce a profile from smaller, poorer quality and older cell samples.

It provides the tantalising prospect of helping police to solve crimes, particularly "cold cases", previously thought to be impossible to crack.

Cases solved by DNA evidence:

Gary Dobson and David Norris convicted of the killing of Stephen Lawrence

Danny and Rickie Preddie convicted, external of the killing of Damilola Taylor

Robert Napper convicted , externalof the killing of Rachel Nickell

James Hanratty finally shown after 40 years to have committed, external the A6 Murder in 1961

Michael Shirley released after 16 years in prison after being cleared, external of murder

But among the forensic scientific community there are growing doubts about DNA 17's usefulness in criminal trials.

"DNA 17 is a victim of its own sensitivity," says Duncan Woods, a forensic scientist with Keith Borer Consultants.

He says the new test is so much more sensitive than the earlier techniques that it can pick up fragments of DNA that may be unconnected to a crime.

For instance, testing a door handle at a house burglary using DNA 17 may increase the chance of finding the intruder's DNA, but it also increases the chance of finding the DNA of a neighbour who had popped in for a cup of tea, the policeman who responded to the 999 call, and a passer-by who had innocently transferred their DNA to the homeowner when they stood next to each other at a bus stop.

Contamination risk

In its advice for its caseworkers and lawyers, the Crown Prosecution Service says: "Whilst the sensitivity of DNA-17 is such as to increase the risk of DNA contamination from the handling of the samples by the Scenes of Crime Officer and the Forensic Science Provider, it also means that contamination is more easily detected.

"There is also an increased risk of detecting background DNA, which may have been deposited before and after the deposition of the target DNA."

Duncan Woods says every week he is dealing with cases in which DNA 17 has been used to detect a profile from such a small number of cells that he can't reach a conclusion as to its significance.

"That's a pretty regular occurrence," he says.

DNA 17 undoubtedly has huge benefits, in providing police with intelligence that might lead them to a suspect and identifying missing people and human remains. It's also compatible with European DNA databases.

But, together with the new retention rules, there's a sense that the landscape of DNA has changed fundamentally.

With change comes the risk of mistakes, missed opportunities and injustice, as cases work their way through the courts in the years to come.