Mars TGO probe despatched on methane investigation

- Published

Artist's impression: A space tug released the orbiter on its way to Mars

A joint European and Russian space mission is heading to Mars.

Launched from Baikonur in Kazakhstan, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) will study methane and other rare gases in the Red Planet's atmosphere, and also drop a lander on its surface.

Controllers received a signal from the probe late on Monday, confirming it was in good health.

Analysis of tracking data indicated that the 4.3-tonne orbiter was on a good trajectory as well.

The European Space Agency's ExoMars flight director, Michel Denis, speaking from the organisation's operations centre in Darmstadt, Germany, announced the good news: "We have AOS - acquisition of signal; we have a mission. And for the second time, Europe is going to Mars. So, Go, Go Go! ExoMars!"

Esa's director general, Jan Woerner, added: "We are on the way to Mars and this is really a very nice experience, to have this inspiring mission now realised. Let's go forward to Mars and see what we can do."

The Proton rocket blasted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan

The day began for Esa and its Russian counterpart with the thunderous lift-off of a Proton rocket at 15:31 Baikonur time (09:31 GMT).

This vehicle put the TGO in a low-Earth orbit, from where the Breeze-M tug then began a series of engine burns to build up the speed needed to go to Mars.

The cruise to the Red Planet is a seven-month, 500-million-km journey. And even when it arrives, the TGO will take the better part of a year to manoeuvre itself into just the right position around Mars. So, in reality, the satellite's observations will not start in earnest until late 2017.

But when they do, they will represent the first life-detection investigations made at Mars in more than 40 years.

The TGO's instruments can sense the smallest components in the air with remarkable fidelity.

Jorge Vago: "Disentangling the puzzle will not be easy"

Of prime interest, of course, is methane, which exists at levels 1,000 times lower than on Earth. On our planet, the CH4 molecule is present in the parts per million by volume; on Mars, it is in the parts per billion.

But in the harsh environment on Mars, this gas should be destroyed by sunlight relatively rapidly, over the course of a few hundred years.

So, the fact that a signal persists suggests the simple hydrocarbon is continually being replenished somehow.

An obvious explanation is that active geological processes are responsible. Ideas include something called serpentinisation, which yields methane at the end of a chain of reactions when water comes into contact with certain rock minerals.

It is also possible that the methane seen on Mars today is actually an old store that was locked away in ice, perhaps billions of years ago, and occasionally pulses into the atmosphere today when that ice gets melted for some reason.

"This is a fantastic form of ice called clathrates," explained TGO scientist Dr Manish Patel from the UK's Open University.

"It does occur on Earth but you may not be familiar with it. This is ice that contains methane and when it melts it releases that gas and you can actually set it on fire (on our planet)."

Dr Manish Patel: "Some of this gas could be stored in ice clathrates"

But the notion that sub-surface microbes could additionally be making a contribution is not so fanciful, say scientists. After all, single-celled organisms are the main source of methane in Earth's atmosphere.

The TGO satellite will fly around the Red Planet, analysing the chemical fingerprints of the gas to try to get some clues. One such line of evidence would come from the isotopic nature of the carbon element in methane. Life on Earth tends to favour a lighter version of this atom. The TGO will have the sensitivity to discern this kind of detail.

But Dr Jorge Vago, the Esa project scientist on the mission, cautions that definitive answers will be hard to come by.

"I am not sure we will ever be in a position to have a smoking gun, and say 'for sure, it is this'. But little by little, as the mission progresses, we will get better at focusing our hypotheses and what the explanations might be."

Schiaparelli's demonstration landing on 19 October

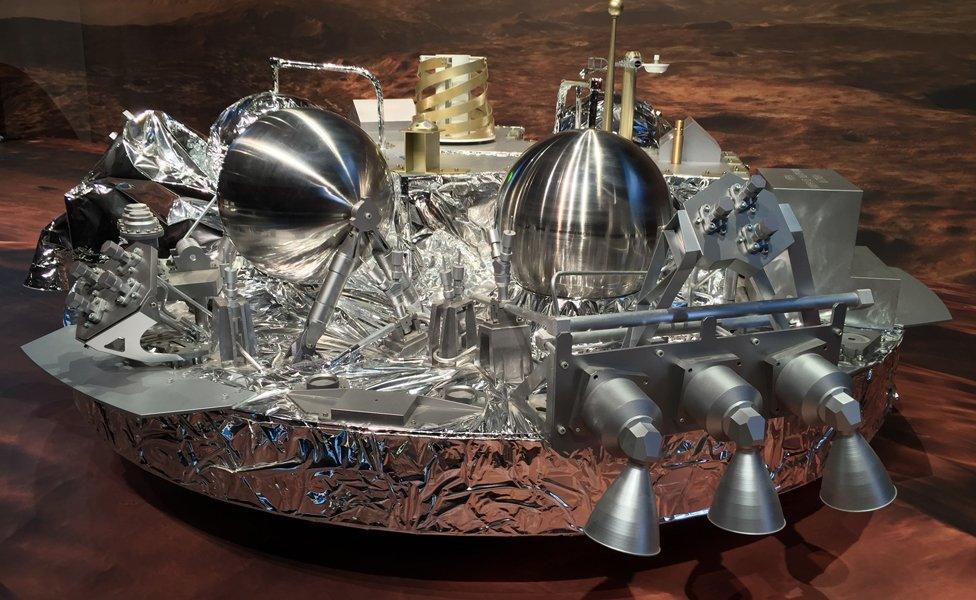

Model of Schiaparelli: The lander will probably work for a couple of days after landing

Schiaparelli will be released by the TGO close to Mars, on 16 October

The probe will hit the top of the Martian atmosphere at a speed of 21,000km/h

It will use a heatshield, parachute and rockets to slow its descent

The final touchdown will be cushioned by crushable material on its belly

The probe will take pictures on the way down, but it has no surface camera

Schiaparelli will make environmental observations until its battery dies

The main goal is to demonstrate its descent radar, computers and algorithms

These will be used in the mechanism that lands the future ExoMars rover

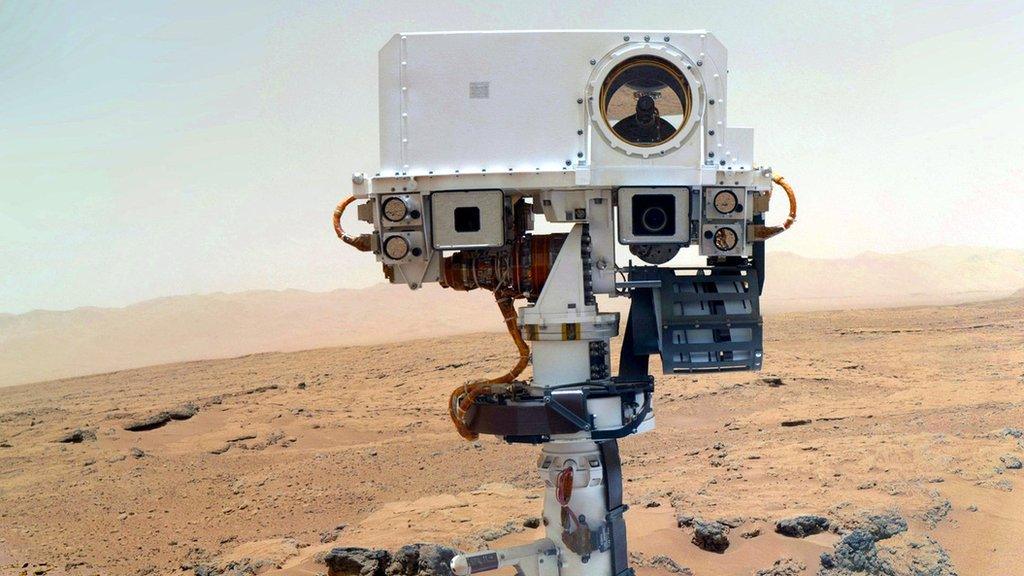

Further lines of evidence should emerge when a second European-Russian mission - a British-assembled rover - launches in a few years' time.

This will drill below the surface, and subject rock and dust samples to analyses designed to detect the chemistry practised by biological systems - either taking place in the present or having done so in the past.

But to get any answers, all the technology will have to be delivered safely to Mars and work - and for Russia in particular this is a high-pressure expectation.

Most of its 19 previous Red Planet missions were outright failures. It is hoping for better fortune by teaming up with Europe.

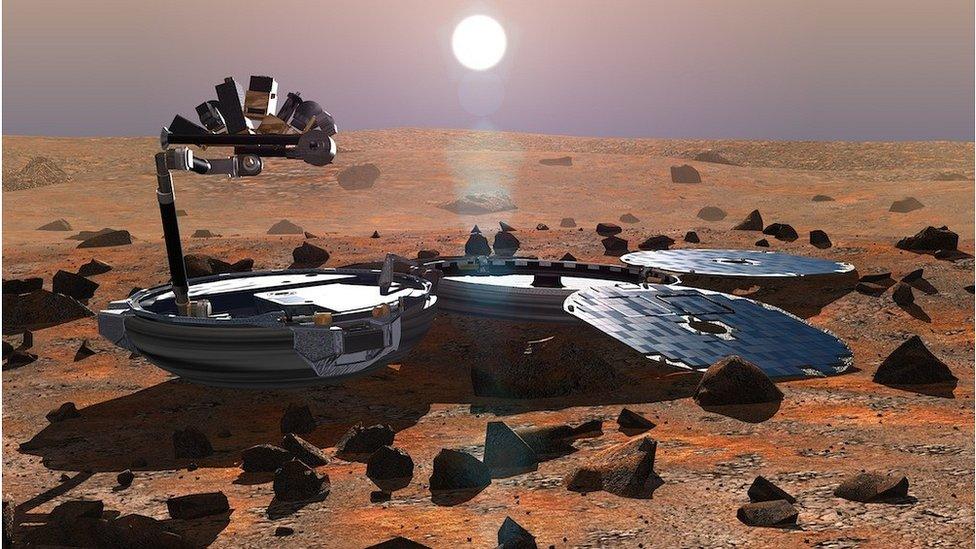

One way the TGO plans to mitigate future risk is by dropping a demonstration lander on the surface in October.

This module, known as Schiaparelli, will carry a number of scientific instruments, but its primary purpose is to test systems needed to get the rover down safely in 2019 or 2021, whichever date is chosen for that endeavour.

These critical landing systems include a radar, computers and their algorithms.

After the European Space Agency launches the first part of an unmanned mission to Mars, it will send a second rocket carrying a rover that will drill for signs of life

Schiaparelli is being targeted at Meridiani Planum - the same place as Nasa's Opportunity rover

The Trace Gas Orbiter was assembled by European manufacturer Thales Alenia Space

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 March 2016

- Published25 November 2015

- Published21 October 2015

- Published24 May 2015

- Published19 September 2013

- Published16 January 2015

- Published16 January 2015

- Published3 June 2013