First big test for Paris climate deal

- Published

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and French President Hollande join in the celebrations

Do you remember the day we saved the world?

When COP President Laurent Fabius smacked down his gavel on December 12, it signalled that agreement had been reached at the UN climate conference in Paris on one of the world's most intractable environmental and economic problems.

After years of onerous, cantankerous and often tedious talks, somehow all 196 participants, like a large collection of cats, had agreed to be herded in the same direction.

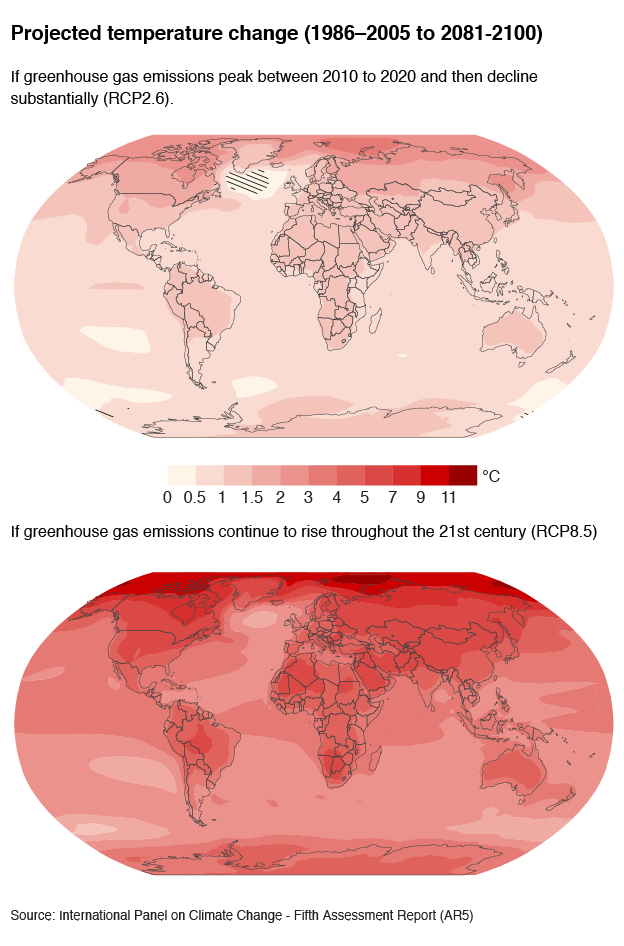

They had agreed to keep global temperatures "well below" 2C and "to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels".

This was a globally significant moment and the celebrations lasted long into the night.

Four months later and almost 170 countries are poised to ink the agreement at UN headquarters on Friday.

The momentum seems to have been maintained since the heady days of Le Bourget in December.

Perhaps it has something to do with record global temperatures in the intervening months, or the recent evidence about the lack of Arctic sea ice? Maybe it's the growing worries over Antarctica?

For now at least, most politicians and most scientists are on the same page. They agree that to have any chance at all of stemming the worst warming, the deal must enter into force. And quick.

That will only happen when at least 55 countries representing at least 55% of global emissions of carbon dioxide sign and ratify the pact, indicating that they agree to be bound by the rules.

New legislation

For some this will involve a debate before parliament, for other countries it will mean new legislation. Some countries like Palau, Switzerland and the Marshall Islands have already taken these steps so will be able to sign and join on 22 April.

The US and China have indicated that they too will do everything they can to join the agreement within the year.

Together they represent almost 40% of emissions so there is a possibility that if enough countries can be persuaded, the deal could come into effect in 2017 or 2018.

Crops could be used to capture carbon

President Obama would love to make sure that his successor can't welch on the deal, especially if the next US leader is a Republican.

Some scientists worry that the rush to put Paris into practice could mean enshrining in international law some worrying ideas.

Keeping temperature rises below 2C and striving to keep them as close to 1.5C will require more than dramatic cuts in carbon emissions.

According to Dr Oliver Geden, from the German Institute of International and Security Affairs, the world will need to remove huge amounts of the gas from the atmosphere.

The vast majority of scientific scenarios to keep below 2C require negative emissions by around 2070, he says.

One idea involves growing crops that capture carbon, burning them to make electricity and then burying the resulting CO2 permanently.

"Those people who will sign the treaty in New York, I suspect that most of them have never heard of negative emissions," he told me.

"They don't have any idea of the amount and requirements of it. They have only heard that 2C is still feasible."

Dr Geden says that the world would need to dedicate land equal to 1.5 times the size of India to keep below 2C. He says it is "science fiction".

"It is magical thinking, it might happen but as long as we can't see that it works on scale, we should not assume that it will be there to save us."

Even if the leaders who sign on Friday are not fully aware of what the long-term implication of the plan is, the act could ultimately work to everyone's benefit.

People make things real by believing in them. If enough savers believe that a bank is about to collapse, and they rush to withdraw their money, they make the idea the reality.

The same can be said of the Paris agreement.

Even if the contents aren't enough to keep temperatures anywhere near 1.5C, if enough people sign up for it and keep the momentum going forward it could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Markets and investors will be the key. If they believe that the extraction of fossil fuels is going to be limited they will not want to stay in that game. The recent collapse of one of the world's leading coal companies, plus the announcement by Saudi Arabia that it sees its future away from oil, all are significant signs on the road.

According to Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, a long-time participant in climate negotiations and adviser to the German government, things can actually change really quickly if people believe that something is inevitable.

"While 1.5C seems almost impossible, you never know how quickly the industrial revolution happens," he said.

"If all the investors decide to not put all their money into fossil fuels, it can happen in 10 years."

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external.

UN climate conference 30 Nov - 11 Dec 2015

COP 21 - the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties - saw more than 190 nations gather in Paris to discuss a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the threat of dangerous warming due to human activities.

Explained: What is climate change?

In video: Why did the Paris conference matter?

Analysis: Latest from BBC environment correspondent Matt McGrath

In graphics: Climate change in six charts

More: BBC News special report (or follow the COP21 tag in the BBC News app)

- Published13 December 2015

- Published11 May 2015

- Published1 August 2013