Arctic winter sees sluggish sea-ice growth

- Published

Sea-ice has a thickness that needs measuring, as well as a surface area

Although the extent of winter Arctic sea-ice has been the smallest on record this year, it is unclear yet whether its volume will also mark a new low.

This latter figure is the best measure of the state of the marine floes.

The most up-to-date data from Europe's Cryosat spacecraft, external suggests sea-ice thickness is tracking close to a "minimum maximum" - but there may still be some growth left in the season.

It will be April before a definitive statement on ice volume can be given.

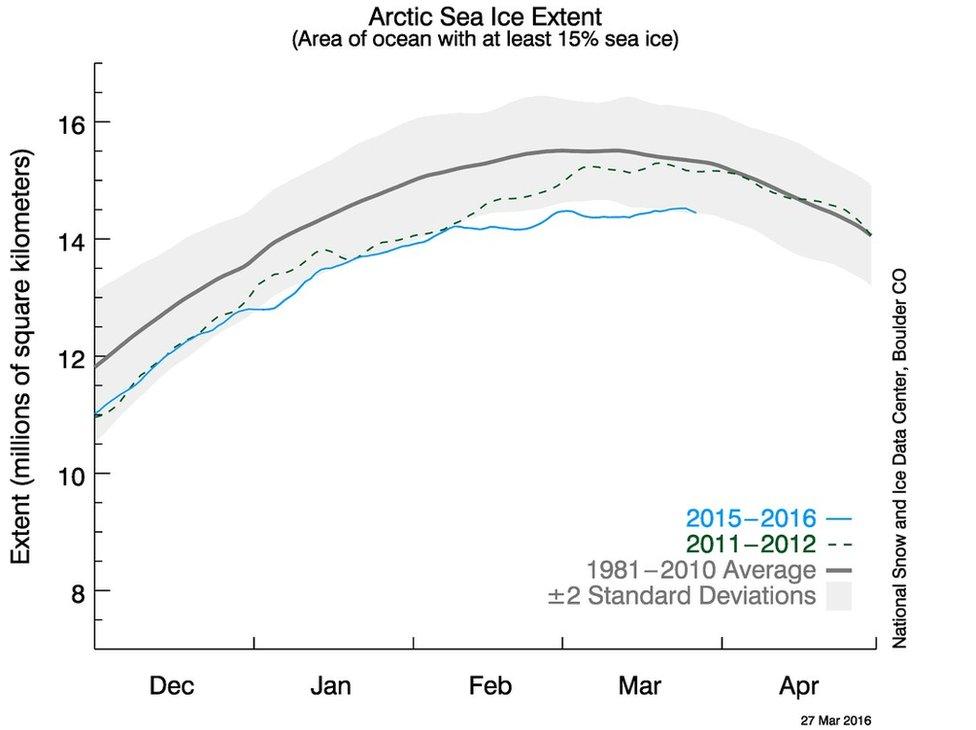

In terms of extent, however, the data is in. Scientists at the US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), external and the country's space agency (Nasa) say the area of ocean covered by floes is now declining after the winter freeze-up.

The largest averaged extent was reached on 24 March, and came in at 14.52 million sq km, they say.

This is a fraction under 2015's figure (14.54 million km), which set a 37-year, satellite-era record.

It should be noted, though, that the difference is so small, it is actually within the errors associated with the measurement.

It had been obvious for some time that floe growth would be sluggish this winter.

Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean through December, January and February were 2C to 6C above average in nearly every region, limiting the freeze-up that normally occurs in the dark months of the polar north.

But ice extent is, of course, just a two-dimensional observation. Scientists are waiting for Cryosat to return its full, three-dimensional data-set.

This European Space Agency platform has a radar altimeter that can be used to calculate the thickness of the floes, yielding an overall volume when combined with area/extent information.

And while Cryosat has also seen sluggish growth (such as in the Barents Sea) during the anomalously warm winter, the Arctic still retains a fair amount of thick, multi-year ice north of Canada.

Artist's impression: Cryosat is the only satellite currently dedicated to the study of Earth's poles

It means that this winter's maximum volume looks very similar at the moment to 2013, when the floes peaked at 24,800 cubic km.

That "minimum maximum" came off the back of a record-setting summer melt in the Arctic.

However, the moment of greatest volume in the floes tends to occur many days, if not weeks, after ice extent has turned its corner. Ice at the very highest, coldest latitudes can continue to accumulate mass even as the periphery at warmer, lower latitudes begins to erode.

"Once Arctic sea-ice has reached its maximum area for the year it continues to thicken for about a month as seawater beneath the ice freezes to the under-ice surface. We expect the ice to reach its maximum amount towards the end of March or start of April," explained Rachel Tilling, a Cryosat researcher at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, external (CPOM) at University College London, UK.

"But the ice has only thickened by about 8cm since February, when usually it thickens by twice this amount."

Prof Andy Shepherd, the senior scientific advisor to the Cryosat mission, told BBC News: "Early March saw slow growth and if that is maintained then I suspect the winter volume will end up being lower than in 2013 - but it will be very marginal.

"This does all illustrate though why we need a three-dimensional view of the ice. Strong winds can cause the same amount of sea-ice to pile up in a smaller than usual area, which you would miss if you considered just the extent of the floes - how widely the ice is spread across the ocean.

"And if this happens, the ice can actually become more resilient to summer melting depending on where it ends up, which emphasises the importance of knowing how thick it is, too," the Leeds University expert said.

European scientists recently petitioned the European Commission and the European Space Agency to start work on a Cryosat follow-up mission.

The spacecraft is currently operating beyond its design life, and researchers are concerned the ageing mission could die in orbit at any time, depriving them of its unique data.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published24 March 2016

- Published2 March 2016

- Published17 December 2015

- Published26 October 2015

- Published19 May 2014