'Oldest axe' was made by early Australians

- Published

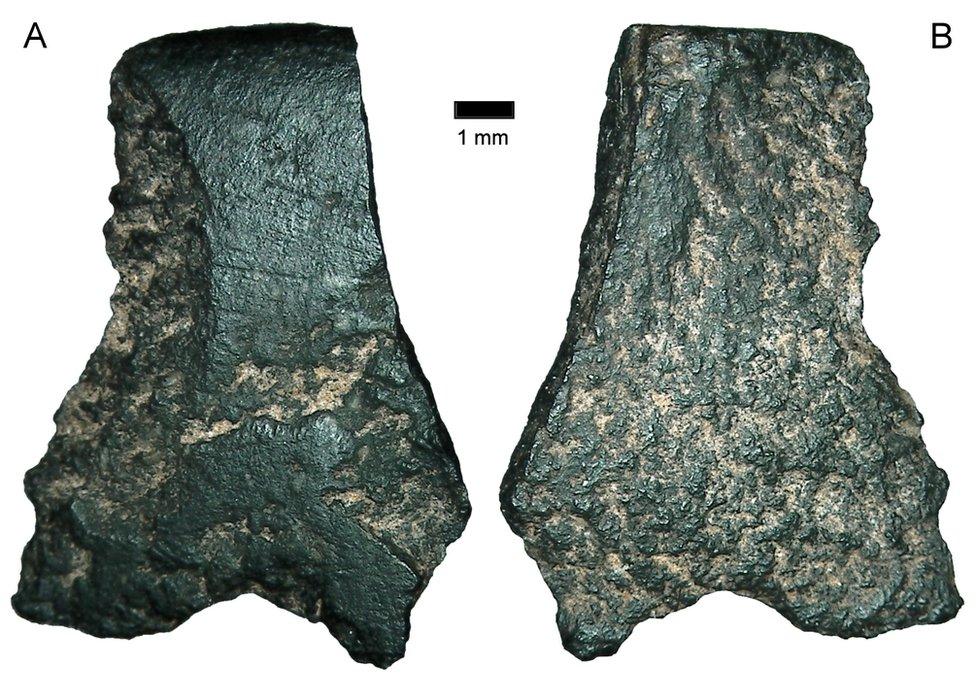

The evidence is a small piece of basalt just 11mm long

A tiny stone fragment from north-western Australia is a remnant of the earliest known axe with a handle, archaeologists have claimed.

The fingernail-sized sliver of basalt is ground smooth at one end and appears to date from 44 to 49,000 years ago.

This is not long after humans first settled Australia - and several thousand years earlier than previous, similar ground-stone discoveries.

The findings appear in the journal Australian Archaeology, external.

Although much older "hand axes", usually made of flint, have been found across Europe and Africa - one well-known example found on a Norfolk beach is thought to be 700,000 years old - those were very different tools.

Axe blades made from harder stone, painstakingly battered into blades, are known from sites in several discrete locations around the globe including northern Asia, the Americas - and Australia.

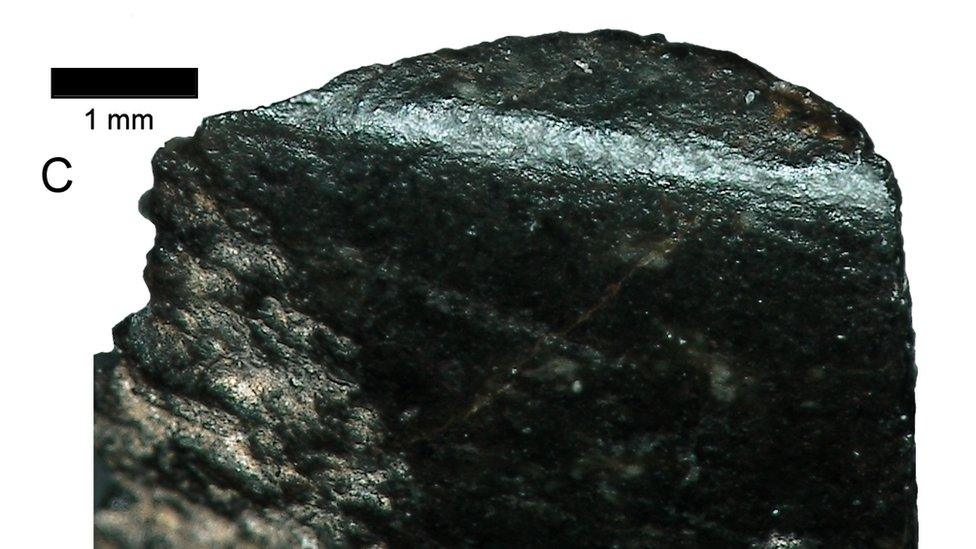

The surface at the top of the fragment is ground smooth

Archaeologists have deduced that they were usually attached to a handle to form a tool much like a hatchet. Such implements are often associated with the development of agriculture but ancient examples from Australia vastly pre-date agriculture anywhere in the world - and this latest fragment is even a good 10,000 years older than similar finds, external in the far north of the continent.

It suggests an adaptation to a new environment by the very first Australians, according to the research team who discovered it.

"We know that they didn't have axes where they came from," said Prof Sue O'Connor from the Australian National University.

"There's no axes in the islands to our north. They arrived in Australia and innovated axes."

Prof O'Connor first dug the fragment up in the 1990s, along with many other objects and samples, from a rock shelter called Carpenter's Gap in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

It was only when she and her colleagues were studying that haul in more detail in 2014 that they discovered the tiny piece of polished stone. Closer analysis suggested it could be a chip hewn off the blade of a stone axe as it was re-sharpened.

"Nowhere else in the world do you get axes at this date," Prof O'Connor said.

"Australian stone artefacts have often been characterised as simple. But clearly that's not the case when you have these hafted axes earlier in Australia than elsewhere in the world."

The fragment was dug up in the 1990s in Windjana Gorge National Park, Western Australia

Evidence like this tell-tale basalt chip is difficult to come by. A ground-stone axe would take an investment of hours or days to manufacture and would then probably be used for years - so there are not many of them to be found.

But they are also not very widespread, according to co-author Prof Peter Hiscock from the University of Sydney.

"Although humans spread across Australia, axe technology did not spread with them," he said. "Axes were only made in the tropical north, perhaps suggesting two different colonising groups or that the technology was abandoned as people spread into desert and sub-tropical woodlands."

That north-south discrepancy persists in the archaeological record, Prof Hiscock added, until axes become more common across Australia within the last few thousand years.

The researchers believe the stone came from an axe head like these

Prof John Shea is a stone tool expert at Stony Brook University in the US. Commenting on the new ground-stone finding, he said its very singular nature makes it difficult to draw confident conclusions.

"The evidence is essentially one flake - one piece of stone out of hundreds and hundreds that they've excavated from this rock shelter site," he told the BBC. "They would make a stronger case if they could show that similar chips with edge abrasion occurred at a greater number of sites."

Further finds, Prof Shea explained, could link this very ancient discovery to times and locations where ground axes are more common.

Without that link, he said there is "still reason for doubt" that the little fragment is, indeed, from an axe blade.

"It could've been smoothed off for some other reason. It might have been the edge of a tool, abraded to make it smooth so that it doesn't cut into the handle that it's lashed to, or it doesn't cut the hand of the person using it.

"But it's a cool find. Again and again, the archaeological record suggests these people were far more clever than past archaeologists were willing to give them credit for. The aboriginal Australian ancestors had a lot more complex technology than we think they did."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published14 October 2015

- Published25 November 2014

- Published11 July 2013

- Published27 January 2011