Tim Peake: What has Britain's astronaut achieved?

- Published

Tim Peake grabbed the headlines for blazing a trail as Britain's first government-funded astronaut but it's fair to ask what his six months in space have actually achieved.

Addressing the Brit Awards in a fake tuxedo, running a virtual London Marathon, playing with spheres of water live on television - all these are eye-catching moments but what did his mission add up to?

With ministers committing nearly £80m to the European Space Agency's (Esa) human spaceflight programme - an essential contribution to secure Tim's place in orbit - the question can be answered in different ways.

You can assess the research he has carried out in orbit or the profile he has given to the UK's space industry or the inspiration he's provided to a new generation.

Let's start with the last of those because the man himself has always wanted to enthuse children about science and engineering to help encourage a British technological renaissance.

Several years ago, just after he had started training in Houston, we met at a restaurant near the Nasa centre and Tim's face lit up when he described ideas for engaging schools in space-related experiments.

So how did he do?

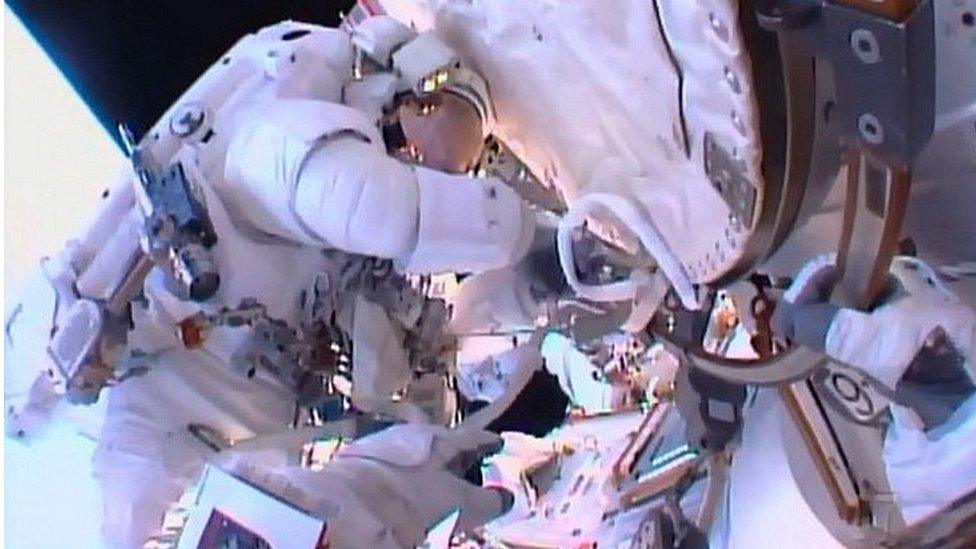

During his first spacewalk

Running a marathon on a treadmill in space

Well, the numbers are pretty staggering. By the latest estimate from the UK Space Agency's education specialists, at least one million pupils in British schools have been involved in his projects so far.

And, because a detailed analysis has yet to be done, the total may in reality be far higher.

Some 30 projects ranging from fitness challenges to computer coding to amateur radio hook-ups made up what ranks as the largest public engagement exercise for any Esa astronaut.

Take the Rocket Science scheme: about 8,600 packets of seeds from rocket plants were sent to thousands of schools and other academic institutions reaching more than 600,000 children.

Half the packets contained seeds that had spent six months in space, the other half held seeds that had stayed on the ground - and in classrooms across the country pupils are cultivating the plants to see if there's a difference.

Tim Peake explains how schoolchildren can grow rocket seeds that have flown with him in space

Libby Jackson of the UK Space Agency says the exercise allows teachers to explain some key principles in research such as blind trials and randomisation, and to emphasise the importance of sustainability in food production.

"Add space as the context and it makes it all the more exciting," she says. "The enthusiasm has been fantastic."

Then there were live link-ups in which Tim, floating in front of an ISS camera, could speak directly to children themselves.

The Cosmic Classroom saw lucky kids gathered for an event in Liverpool but a further 400,000 watched a webcast, and all of them had a chance of posing questions.

At the same time, special exhibitions called Destination Space were staged at 20 science centres around the country and some 350,000 have attended so far to learn about Tim's mission.

Will any of this make a difference to the number of children choosing to study the STEM subjects - science, technology, engineering and mathematics?

The first test will come in September when schools see who confirms for those classes but it will take many years to get a genuinely reliable answer, particularly for a sense of how many then go on into STEM careers.

Tim Peake strides out to the Soyuz space ship that took him to the International Space Station

In the first research of its kind, a team from University of York will attempt to investigate this over the coming years - looking at whether there really will be a "Tim Peake effect" like the "Apollo effect" in which the Moon landings fired up a whole generation.

Libby Jackson says the anecdotal evidence of a positive response is already clear, and she adds: "I haven't met a teacher or parent who hasn't said it's all great - I think the numbers engaged in Tim's mission will be staggeringly high."

And that engagement will not end with his return. While 650 primary schools used Peake-related materials in their teaching this year, the total next year will be 750 - and excitement will surely build as Tim tours the country on his return.

Space station science

So what about Tim's involvement in the science on the space station?

By their very nature, the 250 experiments under way tend to be long-running so no single astronaut will ever have a pivotal role in them during their time on board, let alone be able to claim a 'eureka' discovery.

But Tim has done his bit in a wide range of projects, some relevant to people on Earth, others aimed at future space missions, including allowing his own body to be used in a range of medical experiments. A good question would be to ask how many blood samples he's taken.

Arriving on board the International Space Station

He took part in an airway study in which his exhalations were monitored for nitric oxide which may be an indicator of internal inflammation - relevant to asthma sufferers on Earth and to future astronauts visiting the dusty environments of the Moon or Mars.

He worked on an investigation of metal alloys in which samples are heated to 2000C and levitated - a technique, impossible back here, which avoids any risk of contamination from the container holding the experiment.

He helped to study the endothelial cells that line blood vessels and degrade with ageing. These appear to grow differently in microgravity, so samples have been cultivated in a growth medium and will be analysed back on the ground.

By remote control, he steered a robotic rover in a simulated Martian terrain in Stevenage to test how future astronauts could guide robots and work in tandem with them.

And packed beneath Tim's seat for the return trip are samples of bacteria which were positioned on the outside of the ISS, external, a project run by the Open University and Edinburgh University to explore the limits of where life can survive.

Prof Mike Cruise, who heads Esa's human spaceflight science advisory committee, told me that while "you can't unpick the role of any individual person", Tim had "exceeded expectations" and that his "personal authority" had helped to reach people who would not normally be interested in science.

'Brilliant ambassador'

Finally, what has Tim Peake's mission done to highlight Britain's space industry, worth at least £10bn, but often operating without much public or political attention?

According to Lord Willetts, a former science minister, Tim has been "a brilliant ambassador" and he says "his flight has achieved more than we dared hope".

A view of sunrise from the International Space Station taken by Major Peake

It was David Willetts, at a crucial Esa meeting in 2012, who skilfully negotiated a relatively minor role for Britain in the agency's human spaceflight programme which helped secure Tim's mission.

"It's hard to measure, but I believe Tim has given Britain some real confidence that we are a serious player in space. People didn't recognise that we design satellites and instruments for Mars and beyond, that a Mars rover is being built in Britain."

The hope will be that further big industrial orders will follow, boosting the scale and ambition of the space projects undertaken here.

For decades, successive governments had shown no interest in sending people into space - the first Brit to make it, Helen Sharman, flew with the Russians after winning a competition.

David Willetts is among those hoping that Tim's flight will not be the last. Like many, he's become an enthusiast, seeing the fervour whipped up among children and the value of having a glamorous standard-bearer for a potentially vast industry.

And the excitement is infectious. A few weeks ago, walking along a corridor in the House of Lords, his mobile rang. It was a Houston number. Tim Peake, hurtling 250 miles above the planet, was calling for a chat.

A British astronaut was ringing a peer in Parliament - without any formal Cabinet decision or public discussion, we have suddenly become a spacefaring nation.

The question is whether other missions will follow. And that depends on the strength of the Tim Peake effect, and whether it's enough to convince ministers to keep paying.

Tim Peake in space:

Special report page: For the latest news, analysis and video

Guide:, external A day in the life of an astronaut

Explainer: The journey into space and back

Test yourself: Do you have what it takes to be an astronaut?

Timeline: How Tim Peake became a British astronaut

Quiz: How dangerous is life in space?

Highlights: Scenes from the trip in video

- Published14 June 2016

- Published15 January 2016

- Published16 January 2016

- Published15 December 2015