Rosetta comet probe given termination date

- Published

The Rosetta spacecraft arrived at the comet in August 2014

The Rosetta probe will be crash-landed on Comet 67P on Friday 30 September, the European Space Agency has confirmed.

The manoeuvre, which is expected to destroy the satellite, will bring to an end two years of investigations at the 4km-wide icy dirt-ball.

Flight controllers plan to have the cameras taking and relaying pictures during the final descent.

Sensors that "sniff" the chemical environment will also be switched on.

All other instruments will likely be off.

Flight dynamics experts have still to work out the fine details, but Rosetta will be put into a tight ellipse around the comet and commanded to drop its periapsis (lowest pass) progressively. A final burn will then put the satellite on a collision course with the duck-shaped object.

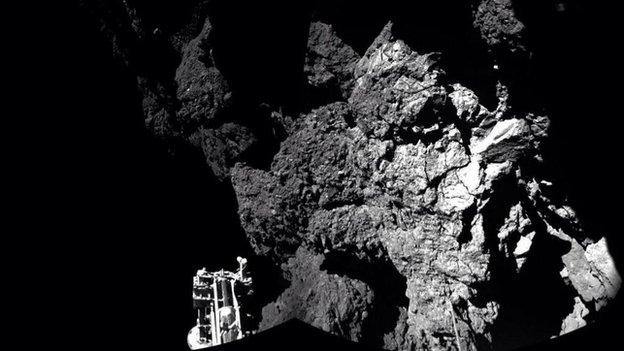

Mission managers have previously talked about bringing Rosetta down in a place dubbed "Agilkia" - the location originally chosen to land its surface robot, Philae, in November 2014.

In the event, Philae bounced a kilometre away, but Agilkia's relatively flat terrain is an attractive option still, although other targets are being studied.

Controllers may aim again for "Agilkia", which is on the "head" of the duck-shaped comet

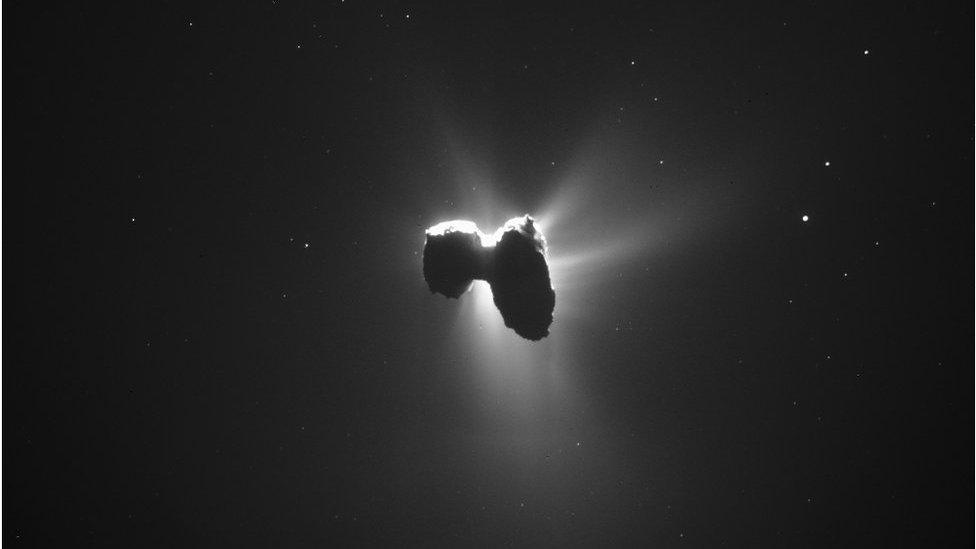

Having swept around the Sun last August, Comet 67P is currently on a trajectory that is taking it away from the inner Solar System towards the orbit of Jupiter.

Today, the probe is nearly half a billion km from the Sun.

This means the amount of light falling on Rosetta's solar panels is gradually diminishing; and, as a consequence, it has less power day by day to run its instruments and sub-systems.

Engineers would soon have to put the satellite into hibernation mode if they wanted to use it long term - during 67P's next encounter with the Sun in a few years' time.

But having already spent 12 years in space, battling huge temperature swings and damaging radiation, not to mention a much-reduced fuel load - there is little confidence Rosetta will still be operable so far into the future.

The crash-landing on the other hand offers the opportunity to get some very close-in science to complement the more distant remote sensing it has been doing.

Controllers will try to maintain contact with the satellite for as long as possible during the final descent.

Much will depend on how well Rosetta copes with the dusty environment around the comet.

Recent months have seen several occasions when the probe's navigation equipment, which tracks the stars to define a position in space, has got confused in the maelstrom of particles emanating from 67P's surface.

This has tripped the satellite into a "safe mode" that shuts down all non-essential operations, including instrument observations.

Rosetta will need to be commanded not to do this in the minutes before impact.

Crash-landing has become a common way to end the missions of planetary probes.

Most have been very high-velocity impacts, but a few, like the one Rosetta will attempt, have been walking-pace touchdowns.

In 2001, the US space agency's Near Shoemaker probe put down on the asteroid Eros so gently that it continued to work for a further two weeks at the surface before engineers eventually determined to terminate communications.

This will not be the case with Rosetta, however. Controllers are expected to program an auto shutoff, which will be triggered at the moment the satellite hits 67P.

Even if by chance its antenna were to survive the crush, Rosetta will not be calling home.

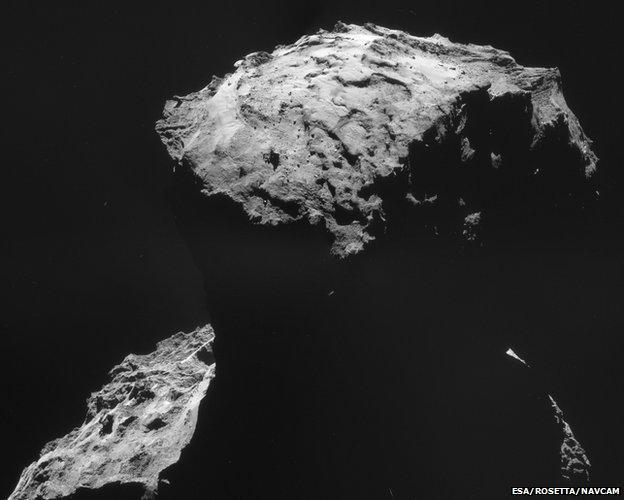

Comet 67P - "Space duck" in numbers

A full rotation of the body takes just over 12.4 hours

The axis of rotation runs through the "neck" region

Its larger lobe ("body") is about 4.1 × 3.3 × 1.8 km

The smaller lobe ("head") is about 2.6 × 2.3 × 1.8 km

Gravity measurements give a mass of 10 billion tonnes

Mapping estimates the volume to be about 21.4 cubic km

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published1 April 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published22 January 2015

- Published16 November 2014