Juno mission: Jupiter probe on course for orbit manoeuvre

- Published

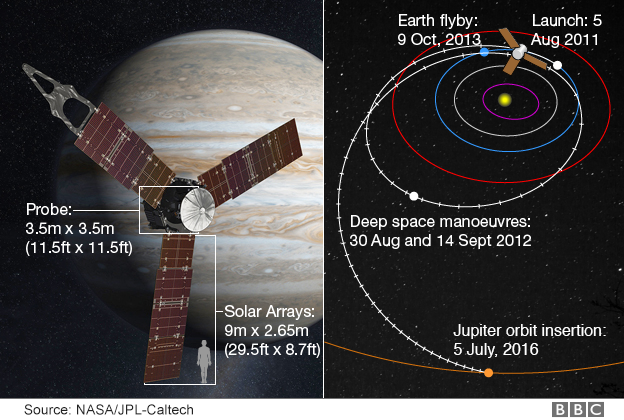

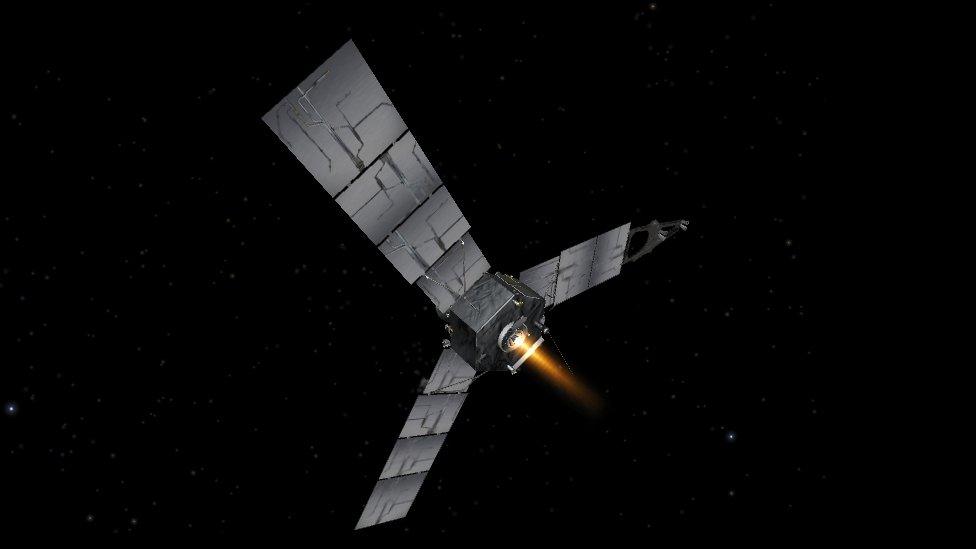

Juno has been travelling through the Solar System since 2011

The US space agency (Nasa) says its Juno probe is on course to go into orbit around the Planet Jupiter.

The satellite is described as healthy and ready for what scientists concede will be a risky manoeuvre.

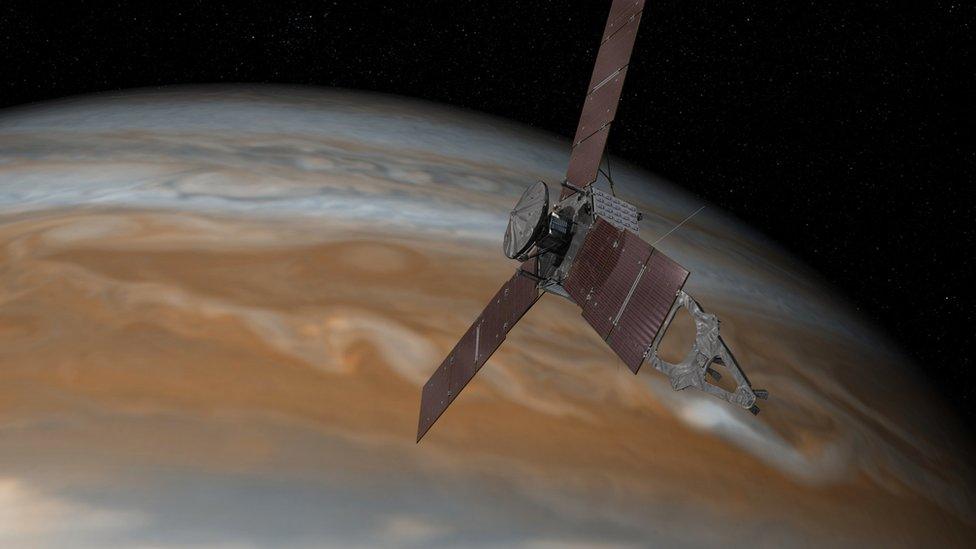

Juno has to execute a precise rocket firing to slow itself sufficiently to get captured by the giant world's gravity.

If it succeeds, researchers should get their best ever view of what lies beneath Jupiter's stormy clouds.

Jupiter approach

The 35-minute orbit insertion burn - timed to to start at 03:18 GMT (04:18 BST) on Tuesday - is sure to jangle the nerves of everyone here in mission control at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California.

If the engine fails to fire at the right time or for an insufficient period, this $1.1bn (£800m) venture will simply fly straight past Jupiter and into the oblivion of deep space.

Juno will not have its main dish pointed at Earth during the braking procedure, so the mission team will have to follow events via a series of simple tones sent back through the probe's low-gain antenna.

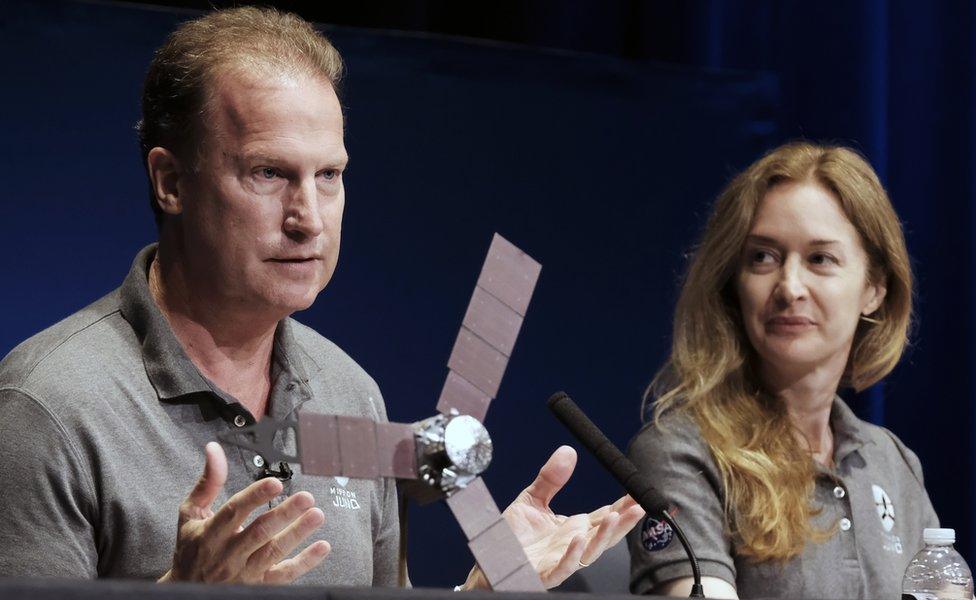

Rick Nybakken, Juno's project manager, said the probe had to thread itself on to a very accurate trajectory to achieve its goal.

"What we're targeting is a space that's tens of km wide. We're going to hit that within 1.2 seconds after a journey of [2.8 billion km]. That tells you just how good our navigation team is," he told reporters.

"We need to get into orbit tonight and I'm very confident we will."

The scientists must sit on their hands, though. The event is so far away, radio messages take 48 minutes to cross the vastness of space. Juno has to do everything on its own.

For scale: No solar-powered spacecraft has worked so far from the Sun, hence its huge panels

Nybakken and Becker say Juno is as prepared as it can be for what lies ahead

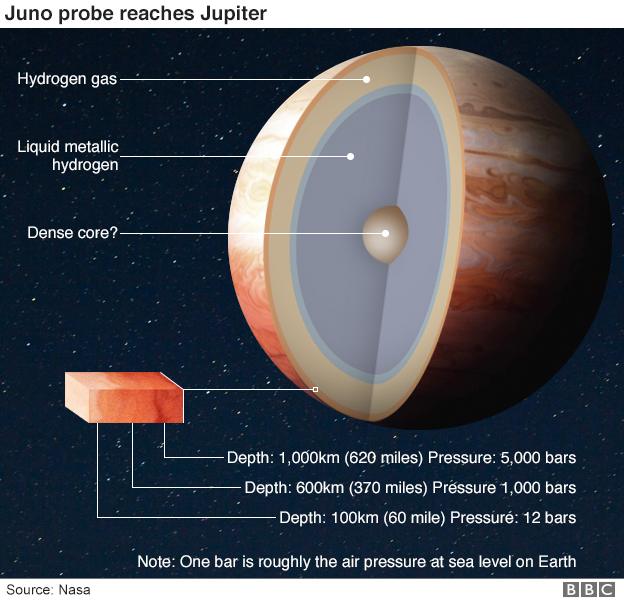

Assuming everything goes to plan, Juno's mission is to look down on the giant world to work out what it is made from and how it is put together.

We should finally discover whether it has a solid core or if its gas merely compresses to an ever denser state all the way to the centre.

We should also gain new insights on the famous Great Red Spot - the colossal storm that has raged on Jupiter for hundreds of years. Juno will tell us how deep its roots go.

Scott Bolton: "Absolutely you can have rain on Jupiter"

The principal investigator is Scott Bolton from the Southwest Research Institute in Texas.

He says he cannot wait to get started: "It is the king of our Solar System. This is it; more massive than all the other planets and everything else in our Solar System combined (other than the Sun)," he said.

"Its zones and belts, its Great Red Spot, its incredible turbulent atmosphere - we've known it for many, many years. It's a gorgeous planet but what Juno is about is looking beneath that surface. We've got to go down and look at what's inside."

The Sky At Night's Chris Lintott explains why Jupiter mission is important

Jupiter is 11 times wider than Earth and 300 times more massive

It takes 12 Earth years to orbit the Sun; a 'day' is 10 hours long

In composition it resembles a star; it's mostly hydrogen and helium

Under pressure, the hydrogen becomes an electrically conducting fluid

This 'metallic hydrogen' is likely the source of the magnetic field

Most of the visible cloudtops contain ammonia and hydrogen sulphide

Jupiter's 'stripes' are created by strong east-west winds

The Great Red Spot is a giant storm vortex twice as wide as Earth

But as enticing as the science is, what worries team-members is the intense radiation around Jupiter, which could upset Juno's electronics, now or in the coming months.

This radiation is a consequence of Jupiter's mighty magnetic field, which whips particles to near light-speed.

Experts have designed Juno's orbit such that it avoids dipping into the most hazardous regions that surround the planet.

Engineers have also put sensitive electronics for the probe's instruments and control systems inside a thick-walled titanium box.

Even so, some equipment, such as the visible camera, is expected to fail before a formal end to the mission is called in early 2018.

JPL engineer Heidi Becker said the success of Juno was going to depend absolutely on the protection it receives from its "suit of armour".

"[Without it], Juno would be experiencing a radiation dose of over 20 million rads, which is like a human undergoing 100 million dental X-rays in a little over a year," she explained.

But it is only by getting in close to Jupiter - a little under 5,000km above the cloudtops on occasions - that Juno can acquire the data it seeks.

The satellite is equipped with nine instruments designed to study Jupiter's spectacular auroras and to look through the planet's many obscuring layers.

A key quest is to determine the abundance of water in the atmosphere - an indicator of how much oxygen was present in Jupiter's region of the Solar System when it formed, and perhaps a tell-tale of any migration it may have made from its original formation location.

In recent weeks, the Hubble telescope has imaged Jupiter's powerful auroras

The uncertainty over the presence of a solid core should be resolved with the aid of very precise gravity measurements.

Scientists have models for how they think the centre of Jupiter behaves, but there is no way they can test the physics in an Earth lab.

"The atmospheric pressure at Earth is about one bar; at the centre of Jupiter it is 80 million bar," explained mission team-member Fran Bagenal from the University of Colorado. "That's like a thousand elephants, one on top of the other, with the bottom elephant standing on a stiletto."

The orbit insertion burn on Tuesday will put Juno in a large ellipse around the planet that takes just over 53 days to complete. A second burn in mid-October will tighten the orbit to just 14 days. It is then that the science can really start.

Nasa plans to run the mission through to February 2018.

Juno will be commanded to end operations by ditching itself in the atmosphere of the planet.

This ensures there is no possibility of the probe crashing into and contaminating Jupiter's large moons, at least one of which, Europa, is considered to have the potential to host microbial life.

There will be updates on Juno's orbit insertion across BBC News, and the BBC Sky At Night programme will run a special programme dedicated to the mission on Sunday 10 July at 20:30 BST, on BBC Four.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published4 July 2016

- Published2 July 2016

- Published3 June 2016

- Published31 August 2011

- Published5 August 2011