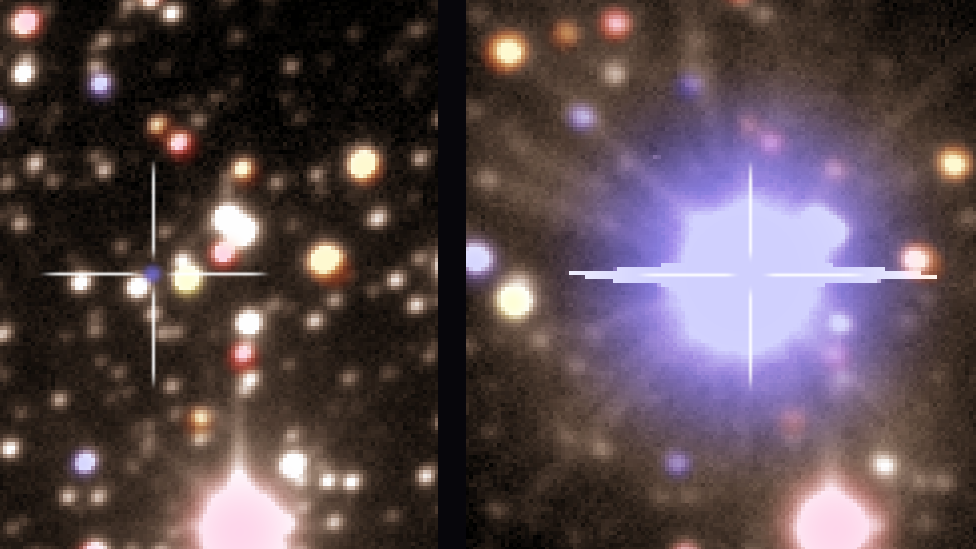

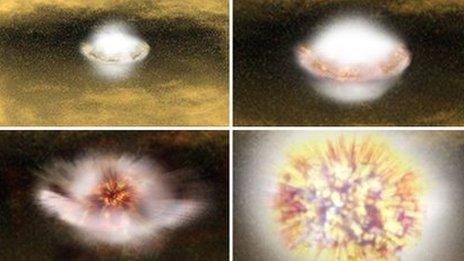

Star snapped before and after nova explosion

- Published

The nova eruption was observed in May 2009 and took place 20,000 light years away

Astronomers have captured rare images of a tiny star before, during and after it exploded as a "classical nova".

In this type of binary system, a white dwarf sucks gas from a much bigger partner star until it blows up - about every 10,000 to one million years.

Now, a Polish team has caught one in the act using a telescope in Chile.

The observations, reported in Nature, external, were made as part of a long-running sky survey that was originally aimed at detecting dark matter.

The consistent stream of images snapped for that project, the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, allowed the researchers to go back and see what the star system looked like before the explosion brought it to their attention in May 2009.

Even though it is 20,000 light-years away - a terribly faint pinprick of light barely visible among brighter stars, even in magnified images - this was a rare opportunity to study the build-up and aftermath of a classical nova.

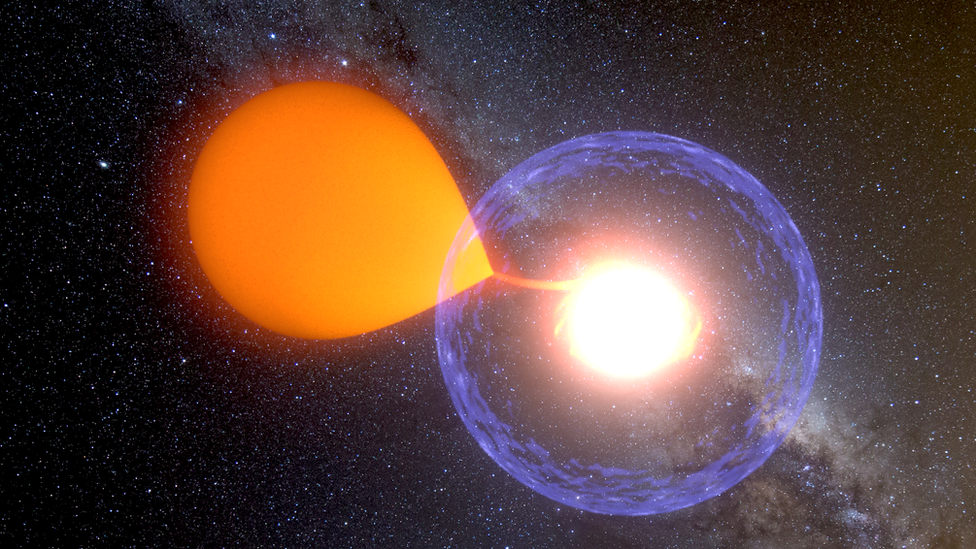

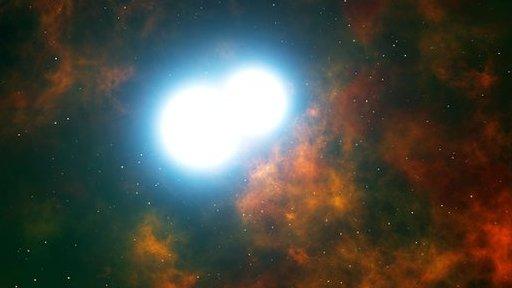

This illustration shows the white dwarf, stealing gas from its partner star and exploding

"Thanks to our long-term observations, we observed the nova a few years before and a few years after the explosion," Przemek Mróz, the study's first author and a PhD student at the Warsaw University Astronomical Observatory, told the BBC.

"This is very unusual, because generally novae only attract attention when they are very bright - when they are in eruption."

Hypothetical hibernation

These violent but poorly understood events begin with a white dwarf, the dead remnant of an average star like our Sun, is locked in tight orbit with a regular, active star.

"The distance between those two stars is very small - actually one solar radius," Mr Mróz said. "Imagine that inside the Sun, you have two stars that are orbiting each other."

So tight is their orbit, which in this case takes just five hours, that the dwarf steadily steals gas from its larger companion.

That extra matter builds up on the surface of the white dwarf until it kicks off a runaway, explosive thermonuclear reaction. Crucially, however, this blast only rips off the extra material; the white dwarf is left behind.

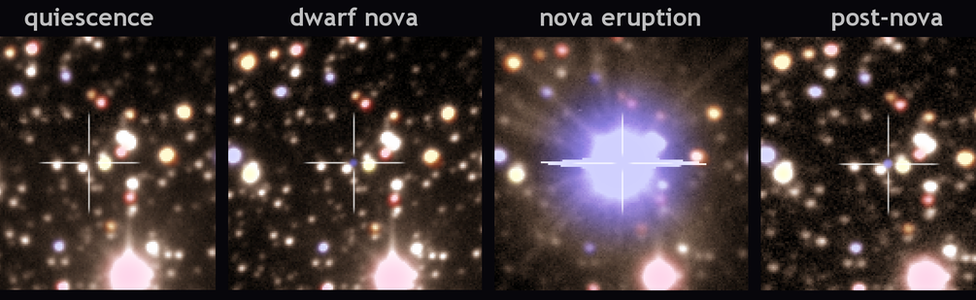

The team has captured a rare snapshot of the nova life cycle

"The entire system survives the nova explosion... so the whole process starts again," said Mr Mróz. "After thousands of years, our nova will awake and explode again but no one will be able to see it."

This is in contrast to a type Ia supernova, which starts with a similar situation but destroys the white dwarf completely in a much bigger explosion.

Mr Mróz's key observations came from studying the light emitted by the system - which is an indication of the mass being stolen by the white dwarf - before and after its dramatic brightness spike in 2009.

"What we observed is that before the eruption, the mass transfer rate in the binary was very low and was unstable. After the eruption, it appears that the mass transfer is much higher and is stable," Mr Mróz said.

"That means that the explosion we observed changed the properties of the binary."

In fact, Mr Mróz and his colleagues argue that their results support a "hibernation" model for classical novae. This means that during the lengthy wait between explosions, the system goes almost completely dark and the white dwarf stops stealing gas altogether.

That model predicts a slow, sputtering transfer of matter between the stars before the explosion, and a relatively fast and bright transfer afterwards - which is precisely what the Polish researchers believe they have captured.

Not put to bed

Other astronomers are less convinced.

"The thing is still just cooling down at the moment - it's not yet steady. So we don't yet know what the long-term brightness is going to be, post outburst, because really we're still seeing the end of the outburst," commented Christian Knigge from the University of Southampton.

Like any scientist, anywhere - he wants to see more data.

The 1.3m Warsaw telescope is part of the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile

"This is very circumstantial," Prof Knigge told BBC News.

But he added: "As observations, as a test bed for our theories of how these explosions work - this really is fantastic.

"We can really measure what the brightness and the conditions were before the eruption; we can use this to inform how we model the eruption; we have a nice measure of how long it takes to decline - and we're going to keep following this.

"I do think this data is going to shed light on classical nova theory - but from my perspective it's too early to claim that this is a clear case of a hibernating system that's now erupted."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published9 February 2015

- Published28 August 2014

- Published13 August 2010