EU's Sentinel satellites dissect Italian quake

- Published

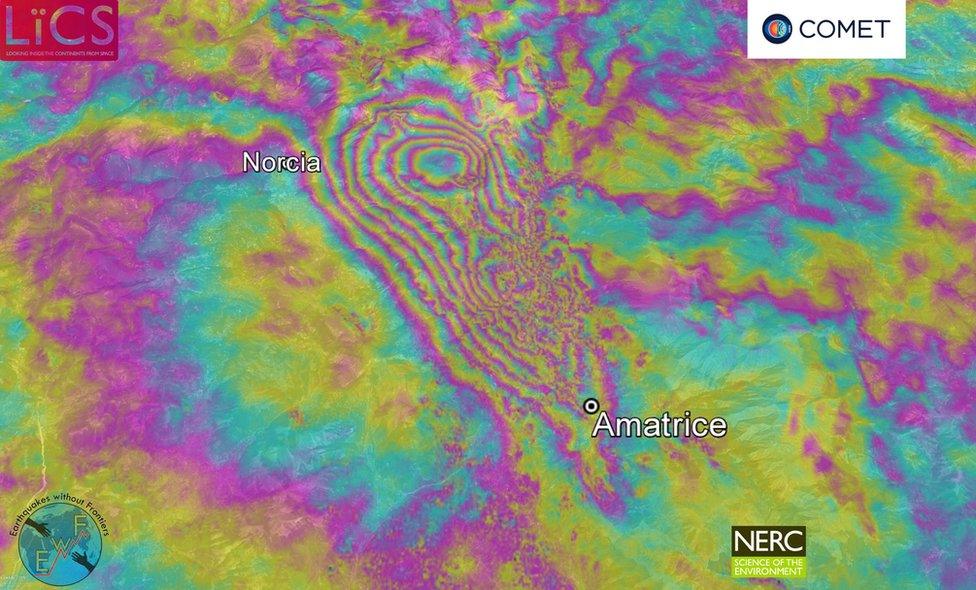

The specialised map will help scientists understand precisely what happened

Europe’s Sentinel radar satellites have mapped the ground movement in the Italian earthquake.

The data show subsidence of up to 23cm (9in) as a roughly 20km-long fault ruptured in the Apennine mountains in the early hours of Wednesday morning.

Scientists will use the information to better understand what caused the magnitude-6.2 event and to make hazard assessments for the future.

Almost 300 people are now known to have died in the big tremor.

The worst affected town was Amatrice, but the settlements of Arquata, Accumoli and Pescara del Tronto were also badly hit.

The specialised picture displayed at the top of this page is what is known as an Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) map.

It is made by combining observations of the ground acquired by orbiting satellites "before" and "after" a quake.

The coloured bands, or fringes, represent movement towards or away from the spacecraft. In this case, each fringe is a step of 2.8cm.

“The InSAR data show that the earthquake has warped the Earth's surface by a maximum of 23cm, causing subsidence in a 25km-long elongate region roughly between the towns of Norcia and Amatrice,” explained Dr Richard Walters from Durham University, UK, who built the map.

“The fault that ruptured was around 20km long. The average slip at depth on the fault was about half a metre, but is concentrated in two major patches, which probably means two separate fault segments ruptured together.

“Most slip took place at depth, with only a small amount reaching the surface.”

Dr Walters is affiliated to Britain’s NERC Centre for Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes, Volcanoes and Tectonics (COMET), external.

Artist's impression: The Sentinel radar satellites offer a powerful capability for geophysicists

To make the map, he used radar data from the European Union’s Sentinel-1a and 1b satellites, external.

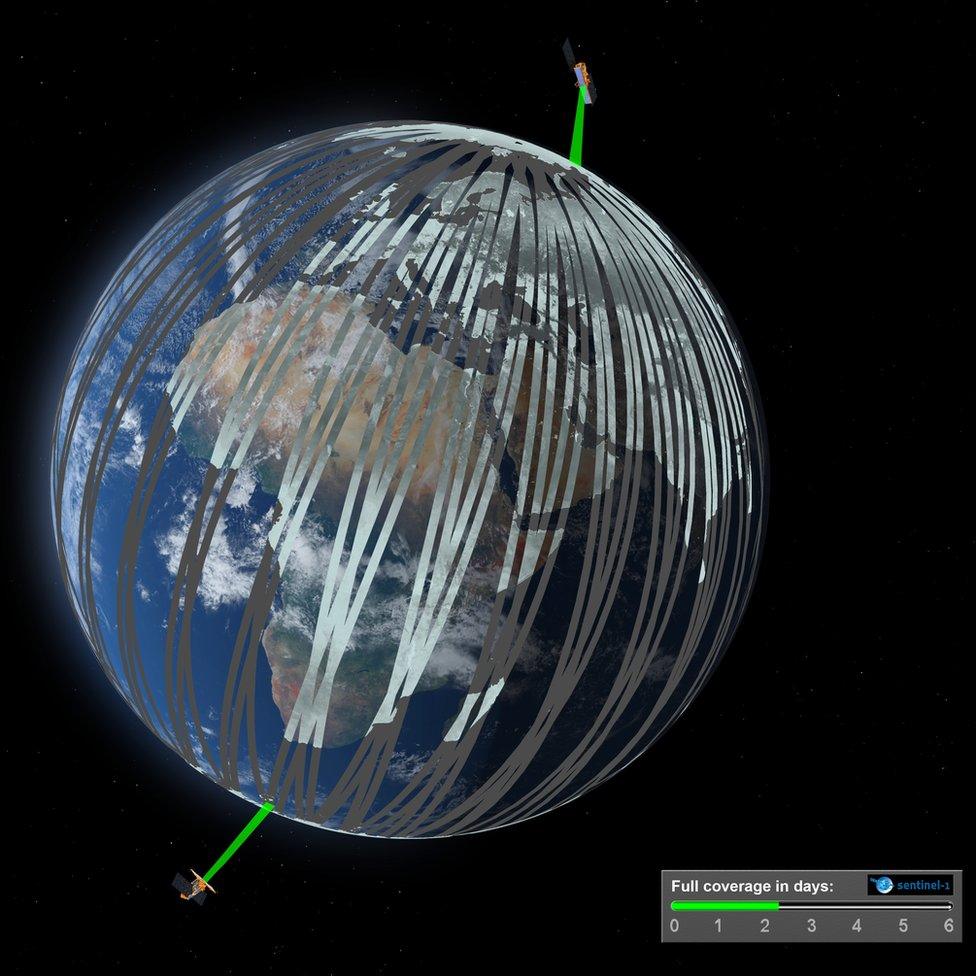

These spacecraft circle the globe, routinely imaging all land surfaces at least once every six days.

Their rapid return to any one location means they were in a position to view central Italy as soon as Friday after the quake, and then again on Saturday.

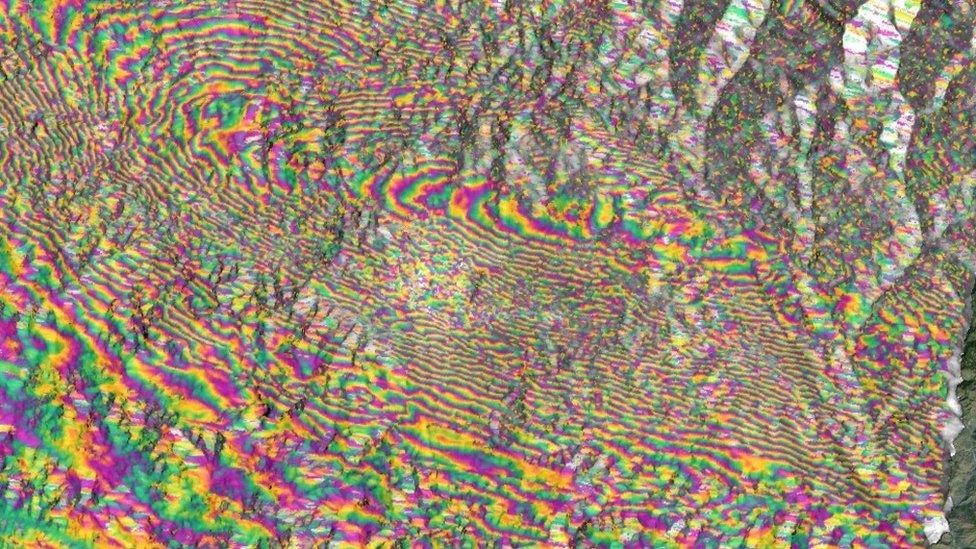

Dr Walters’ point about most of the slip being at depth illustrates the usefulness of InSAR.

Not all ruptures will show an obvious surface expression, such as a buckled road or a newly opened fissure in the ground.

But the InSAR data, in revealing the scale of warping, still permits scientists to trace the fault involved even if some of its sections are somewhat hidden.

This was true of 2009’s damaging quake in L’Aquila, to the south of Amatrice, which killed 309 people.

Surface breaks were small and geologists initially had some difficulty in identifying the fault responsible for the magnitude-6.3 event.

Sentinels 1a and 1b are separated by 180 degrees and will map the entire Earth every six days

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published24 August 2016

- Published29 April 2015

- Published28 April 2016

- Published25 April 2016

- Published2 April 2014