Europe must find another Rosetta

- Published

- comments

End of mission announcement: "Thank you and goodbye"

It was the strangest of atmospheres. Quite sombre, actually. Akin almost to a wake.

Controllers had waited in silence for a radio signal to drop off their screens. It did so, abruptly, external, indicating that the billion-euro Rosetta mission had finally come to an end.

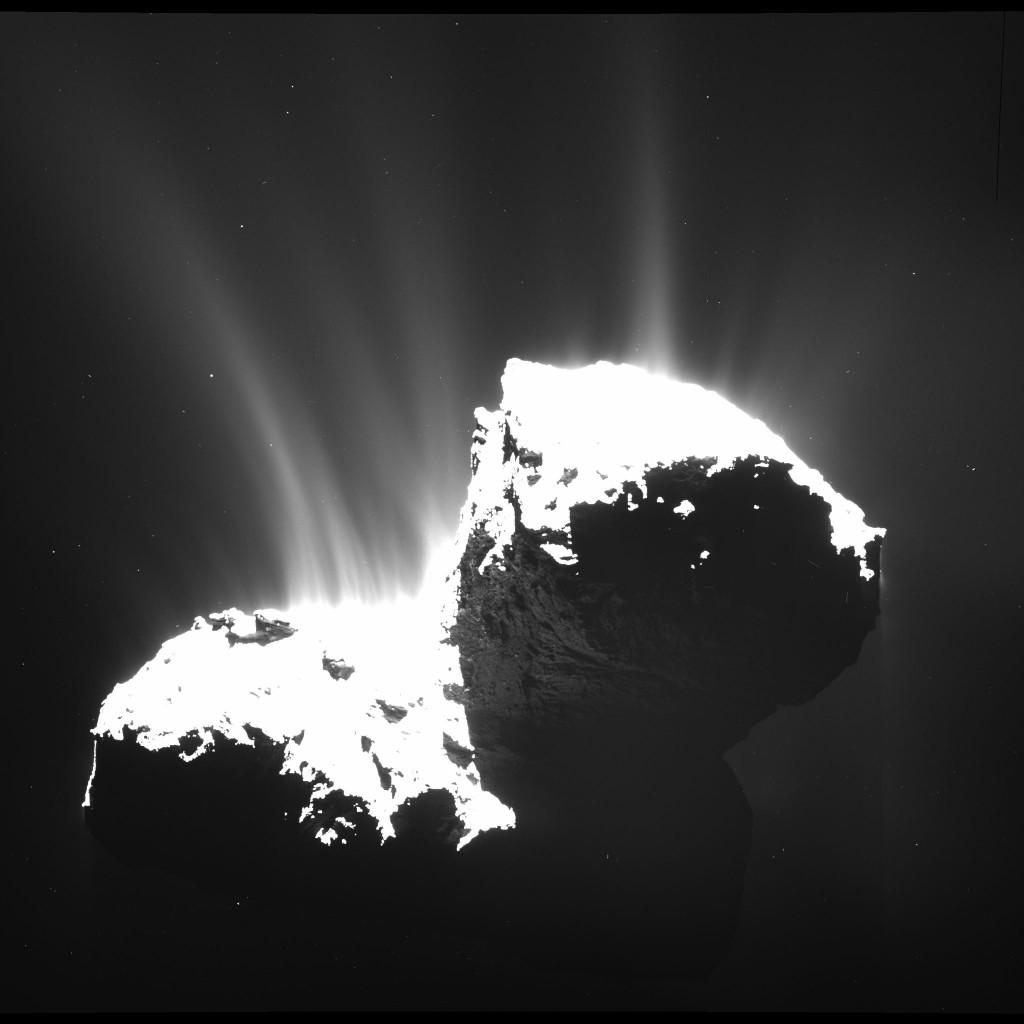

Seven hundred and twenty million km away on the other side of the Solar System, the European probe that had so captivated the world with its examination of a duck-shaped comet had just landed on the surface of the icy object and shut itself down.

“This is the end of the Rosetta mission. Thank you and goodbye,” the spacecraft operations manger Sylvain Lodiot announced over the communications ring. And with that, he took off his headset and walked away to embrace colleagues.

To witness a reaction so muted shouldn’t really have been a surprise. It was after all a bittersweet moment. There were some in attendance who had worked on the project for 30 years.

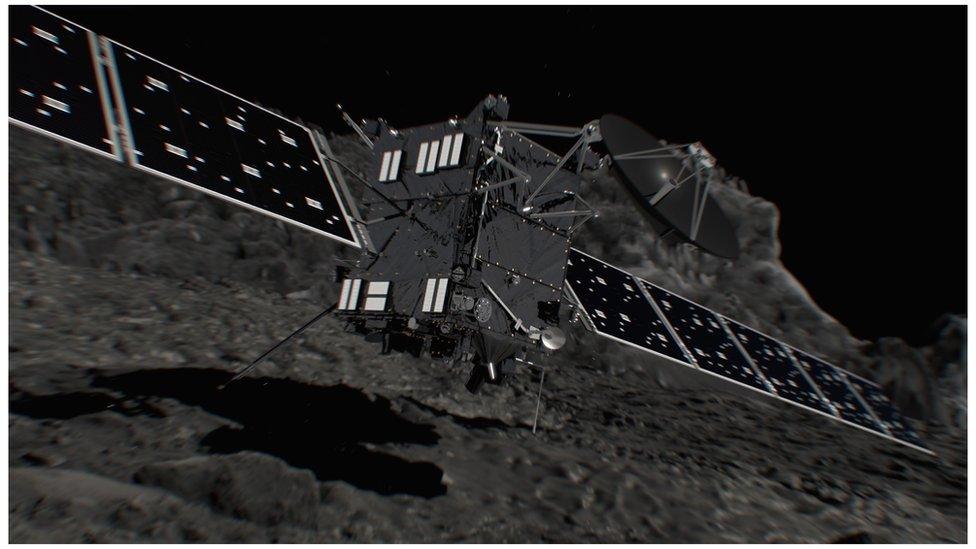

How Rosetta's moment of touchdown on Comet 67P might have looked

Rosetta’s observations as it circled high above Comet 67P have transformed our understanding of the mountainous balls of ice and dust that wander among the planets. And Rosetta’s delivery of the small robot Philae to the surface two years ago was a historic first.

The mission is, without question, a pinnacle of achievement for the European Space Agency. And it was natural therefore that people should feel a particular sense of loss.

Our knowledge of comets has gone through a step-change thanks to Rosetta

“It’s like R.I.P. Rosetta. It’s really sad; I mean really, really sad,” said the Open University scientist Monica Grady, who became something of a face for the mission in the UK.

“You know when you do these things it comes to an end. It’s the end of a real era but it’s the start of the next one because we have to plan the next mission.”

So where next? In terms of Solar System science, the immediate focus of attention turns to Mars. In a couple of weeks, Europe will attempt to put a small probe called Schiaparelli on the surface of the Red Planet. It’s a demonstrator, a prelude to placing the more significant ExoMars rover on our near neighbour in 2021.

The satellite that drops Schiaparelli to the surface has significant work to do also in studying the atmosphere of the fascinating world.

Artwork: The ExoMars rover will aim to drill below Mars' surface to look for life

Also approaching is the much delayed BepiColombo mission to orbit Mercury, and far over the horizon is the Juice venture to Jupiter and its icy moons. This will arrive in the 2030s.

And there’s a satellite called Solar Orbiter, which will launch in 2018 and dare to go extremely close to the Sun.

But it should be said that Esa’s confirmed future missions to small planetary bodies represent an empty portfolio currently.

Its competitive selection process to find large and medium-budget projects have so far overlooked such destinations.

And Mark McCaughrean, Esa’s senior science adviser, believes Rosetta has set such a high bar now that any future comet missions would have to go some way to justify themselves.

“The big question is: what do you do for an encore? Do you go and grab some material and bring it back to Earth - [what we call] sample-return. That’s very expensive, but it could be a big international collaboration.”

As it happens, two smaller comet proposals will be submitted to Esa in the next week for consideration.

One concept, called Castalia, external, would send a spacecraft to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter to study an object that shows very comet-like behaviour.

The other, known as Core (Comet Rendezvous Explorer), would attempt to put another lander on a comet. But, unlike Rosetta’s surface robot Philae that accidentally bounced over 67P, this machine would intentionally hop from place to place to study the varying conditions across the icy body.

One of Core's proposers is Nick Thomas, from the University of Bern, Switzerland. He says there is an imperative now for Europe try to maintain the Rosetta legacy.

“When Europe’s Giotto probe visited Halley’s Comet in 1986, it gave Europe a lead in cometary science that lasted for the next 15 years. And Rosetta is going to do the same for the next 15 years. And what you do is put in a proposal now so that in 15 years’ time we can send the next mission and continue that leadership.”

Comet chocolates: Certain types of space mission engage more than others

And that really is the timescale involved. Even if Castalia or Core is chosen in this next competition round, they will not fly until the late 2020s. The long wait is partly to do with the availability and flow of money, but also has a lot to do with technology development and readiness. It’s a long game.

What should be clear from the Rosetta experience, though, is that the public certainly engage with these types of mission in a way they don’t always with space telescopes.

“For me, we’ve learned that big projects pay off,” said Rosetta’s flight director, Andrea Accomazzo. “This project was conceived 30 years ago. It’s been a massive investment, a massive risk, but also a massive success.”