Huge glacier retreat triggered in 1940s

- Published

Pine Island Glacier drains an area of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet that measures 160,000 sq km

The melting Antarctic glacier that now contributes more to sea-level rise than any other ice stream on the planet began its big decline in the 1940s.

This is when warm ocean water likely first got under Pine Island Glacier (PIG) to loosen the secure footing it had enjoyed up until that point.

Researchers figured out the timing by dating the sediments beneath the PIG.

It puts the glacier’s current changes in their proper historical context, the scientists tell Nature magazine, external.

These changes can now be regarded as unprecedented in thousands of years.

Not only is the glacier going backwards, it is also thinning fast - losing more than 2m in elevation every year.

Other field studies and computer models suggest a runaway collapse might even be possible. The PIG on its own could add up to 10mm to sea levels over the next couple of decades.

"This glacier used to be pinned to a ridge and once it moved away from that ridge, it started to retreat rapidly; and without other pinning points it could continue to retreat rapidly inland, contributing significantly to global sea level," Dr James Smith from the British Antarctic Survey told BBC News.

Dr James Smith: "We needed to understand the longer-term retreat history of this glacier"

The PIG is a colossal feature that drains a region of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet some two-thirds the size of the UK.

It is a marine-terminating glacier, which means its front flows off the land and pushes out into the ocean along the seafloor until its mass begins to lift up and float. Eventually, the buoyant section breaks up to form icebergs.

Currently, the PIG is dumping many billions of tonnes of ice into the ocean every year.

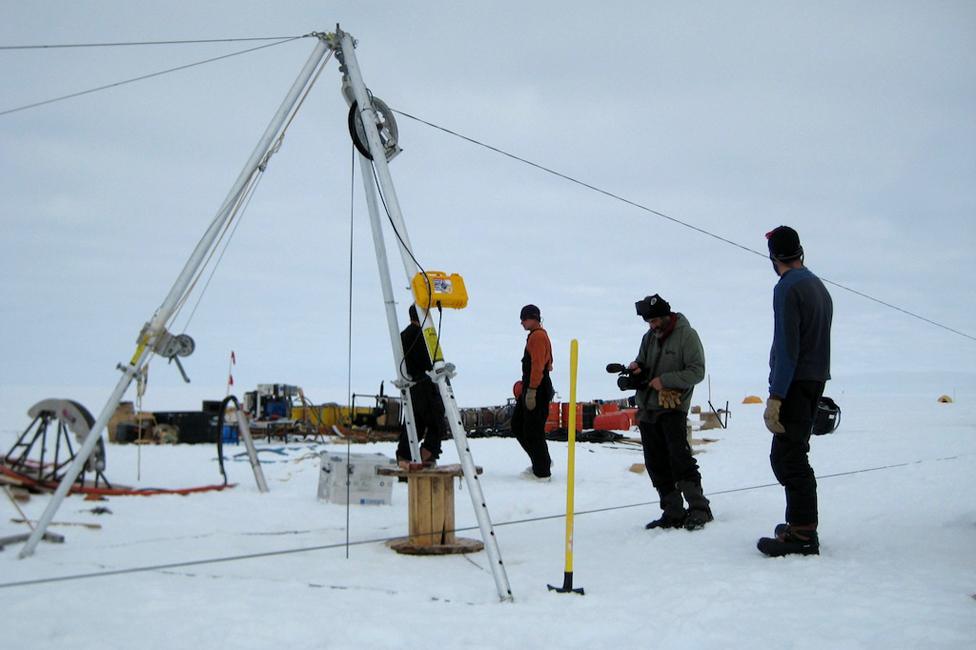

A hot water drill punched a hole through the overlying ice shelf to give access to the ridge

Submersible surveys under its floating front - its "ice shelf" - had revealed the contact point with the seabed once draped over a large ridge.

Having a "grounding line" in such a position would have helped anchor and constrain the whole glacier.

Some of the earliest satellite imagery indicated the PIG must have broken free completely of this pinning bump in the 1970s, but when exactly it started to disengage was far less certain.

It could have been many decades previously; several centuries or even millennia ago.

Now, Dr Smith and colleagues look to have solved this problem.

They drilled through the ice shelf to sample, analyse and date the muddy sediments that cover the ridge. And their investigation reveals that warm water is likely to have started to melt a cavity in the grounded glacier behind the pinch point in about the mid-1940s.

It is hard to imagine the scale of this mighty glacier that is now thinning at a rate of more than 2m a year

One of the reasons they can be sure of the timing is because of where plutonium traces start to appear in the sediment layers.

This radioisotope is a tell-tale signature for the atomic bomb tests that began in earnest after WWII and which peaked in the 1960s.

It leaves open the question of why the unpinning of the PIG occurred when it did, but the team point to the strong warming the region would have experienced following a big El Nino event between 1939 and 1942.

El Ninos are associated with the development of particular wind patterns and warm water movements in the Central Pacific, but the impacts affect weather globally.

"It's an amazing teleconnection that far-field changes can really have a profound impact on the Antarctic ice sheet," said Dr Smith.

Significantly, however, El Nino conditions have waxed and waned over the decades since, but the PIG now continues its relentless retreat.

The PIG calves huge tabular icebergs that drift away into the Southern Ocean

Dr Anna Hogg from Leeds University, UK, monitors Pine Island Glacier on a daily basis using Europe's Cryosat and Sentinel satellites.

These spacecraft can measure from orbit the velocity and thickness of the ice stream.

She commented: "We know from satellite observations that the PIG has sped up and retreated episodically since the late 1970s, so it’s interesting to see that the sediments beneath the glacier record similar periods of variability dating back to the 1940s.

"This erratic past behaviour suggests that we should not expect these colossal glaciers to respond in a steady way in the future, making continuous monitoring increasingly important."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published22 April 2016

- Published26 March 2015

- Published12 May 2014

- Published14 January 2014

.jpg)

- Published11 December 2013