Nickel clue to 'dinosaur killer' asteroid

- Published

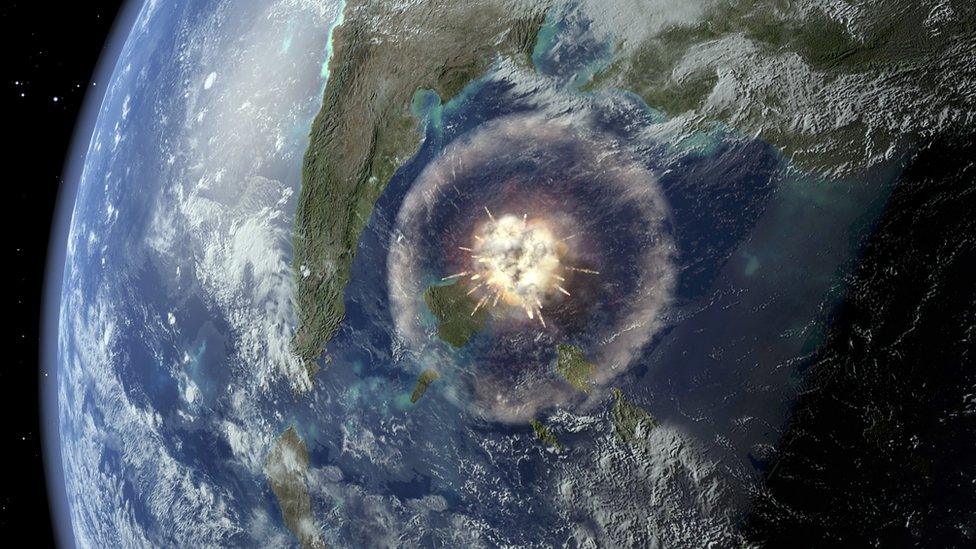

Artwork: The asteroid impact removed 75% of all life on the planet

Scientists say they have a clue that may enable them to find traces of the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs in the very crater it made on impact.

This pointer takes the form of a nickel signature in the rocks of the crater that is now buried under ocean sediments in the Gulf of Mexico.

An international team has just drilled into the 200km-wide depression.

It hopes the investigation can help explain why the event 66 million years ago was so catastrophic.

Seventy-five percent of all life, not just the dinosaurs, went extinct.

The UK-US led team gave an update on its research here at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

The group is currently running all manner of lab tests on the hundreds of metres of core pulled up from under the Gulf in April and May.

One tantalising revelation is that the scientists observe a big nickel spike in the sediments immediately above what has become known as Chicxulub Crater.

This is an important marker that could lead on to the discovery of asteroid material itself.

This animation illustrates the movement of rock in the impact (half of crater)

The presumed 15km-wide space object would have been vaporised in the impact. But some portion of it would have condensed into small spherules in the sky to then rain back down on the bowl.

It should be stressed that the nickel is not in itself an identification of asteroid material.

To have real confidence, the scientists would prefer to see the element iridium.

This is extremely rare on Earth but is frequently associated with meteorites.

Iridium is apparent in the geological layers around the globe that mark the dinosaur-killing event at the end of the Cretaceous Period, but to find it in the actual crater would be an exciting observation. It could result in further insights on the nature of the asteroid that smashed into Earth. One theory is that its metals could have made the environment toxic for many lifeforms.

Philippe Claeys: "Four labs are independently chasing the iridium signal"

Four labs are currently testing for the presence of iridium. Prof Philippe Claeys from the Free University in Brussels says finding the Nickel is a very good sign.

"Nickel behaves chemically in a way that is very similar to iridium; it loves to make strong chemical bonds with iron, just like iridium," he told BBC News.

"So we treat nickel as what we call a proxy for an elevated concentration of iridium. If we see high nickel, it's very likely that we're going to have high iridium."

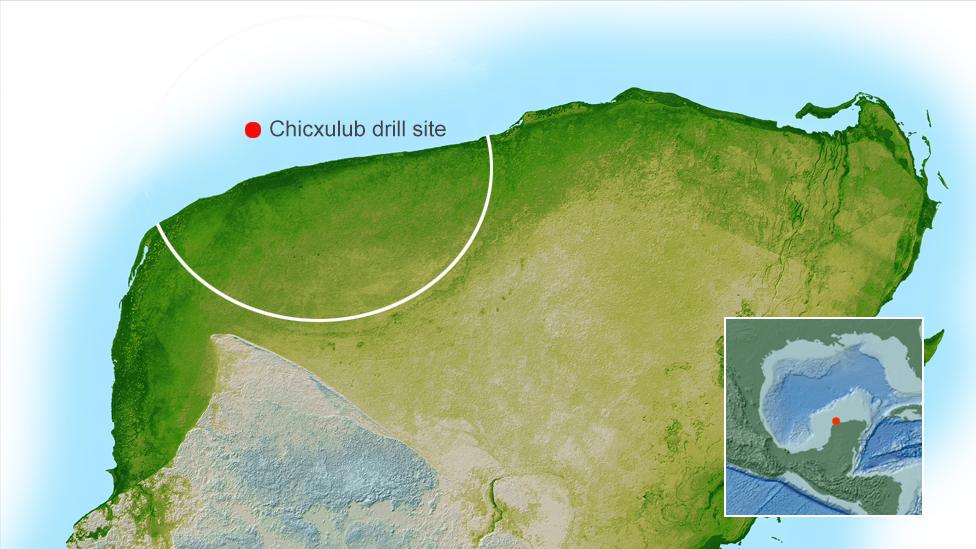

Chicxulub Crater - The impact that changed life on Earth

Today the outer rim (white arc) of the crater lies under Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula

A 15km-wide object dug a hole in Earth's crust 100km across and 30km deep

This bowl then collapsed, leaving a crater 200km across and a few km deep

The crater's centre rebounded and collapsed again, producing an inner ring

Today, much of the crater is buried offshore, under 600m of sediments

On land, it is covered by limestone, but its rim is traced by an arc of sinkholes

Mexico's famous sinkholes (cenotes) have formed in weakened limestone overlying the crater

The project to drill into Chicxulub Crater was conducted by the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (ECORD) as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). The expedition was also supported by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP).

Rock was recovered from more than 1,300m below the modern seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico.

What has thrilled the team is the quality and abundance of material now in the labs.

"Why this is a jackpot core is because we have an expanded section. We have an amount of material that turns into a resolution that allows us to ask lots of questions," said Prof Sean Gulick, the co-chief scientist from the University of Texas at Austin, US.

"For example, if we do see iridium especially in dust, it's not just a tracer for the impactor, it could also tell us something about when this material left the atmosphere and things (the likely dark sky conditions following the impact) started clearing up."

Prof Tim Bralower from Pennsylvania State University is studying the core rocks for the fossils of tiny organisms that lived in the seawater above the crater - from the immediate aftermath of the impact to millions of years hence.

What sort of species are present and how they change up through the sediments should tell him something about how long it took for "normal conditions" to return.

"It's unusual to see such a beautiful record of recovery in this exact location where the mass extinction originated. Basically, 'ground zero'," he said.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published18 November 2016

- Published11 October 2016

- Published25 May 2016

- Published5 April 2016