Recruiting prawns to fight river parasite

- Published

- comments

Susanne Sokolow: "The prawns voraciously eat the snails"

Making sure certain rivers are fully stocked with prawns could prove to be an important contribution to fighting schistosomiasis.

The parasitic worm disease, external is endemic in many parts of the tropics and sub-tropics. Africa is a hotspot.

But it has been shown that prawns will avidly eat the water snails that host the parasite, breaking the cycle of infection that includes people.

The impact was most eloquently demonstrated on the Senegal River.

There, the Diama Dam was built close to the estuary in 1986, blocking the ability of prawns to migrate up and down the water course, decimating their presence.

When scientists restocked the crustaceans, external upstream of the barrier in a controlled experiment, they saw a dramatic fall in schistosomiasis re-infection rates among the local population.

But the ecological consequences of dam construction are often complex and hard to unwrap, and the team could not therefore know for sure how applicable this approach might be to other areas.

So they did an analysis - to look at multiple dam systems worldwide to see how these mapped across decades-long records of schistosomiasis and the traditional habitat ranges of the large migratory prawn, Macrobrachium.

To be clear, no-one actually went out into the field to count prawns, but the results of the analysis were nonetheless compelling: damming was followed by greater increases in schistosomiasis in those areas where prawns had historically been present versus those zones not known to be big prawn habitats.

The inference being that the loss of the crustaceans was a major factor in the rise in infection.

“Where there were dams, schistosomiasis increased, but it increased more - at least double on average - where we expected these predators to be, traditionally - compared to those dammed watersheds where they have not been,” explained Dr Susanne Sokolow from Stanford University and UC Santa Barbara, US, external.

And her colleague, Prof Giulio De Leo, external, added: “We ended up finding that something like 280 million to 350 million people live in areas that are endemic for schistosomiasis and could potentially benefit from this type of intervention (prawn re-introduction).

“We are talking in fact about 40% of the 800 million people that are potentially at risk of schistosomiasis and this is because most of the people tend to concentrate in coastal areas where there is also historical presence of these migratory prawns that happen to be voracious predators of the snails that amplify schistosomiasis.”

Sokolow and De Leo gave details of their latest work at the recent American Geophysical Union meeting, external in San Francisco.

The Diama Dam allowed for the expansion of agriculture along the Senegal River

Diama Dam was built to prevent salt water getting upstream

Its construction permitted the growth of agriculture

Schistosomiasis infection rose rapidly after dam construction

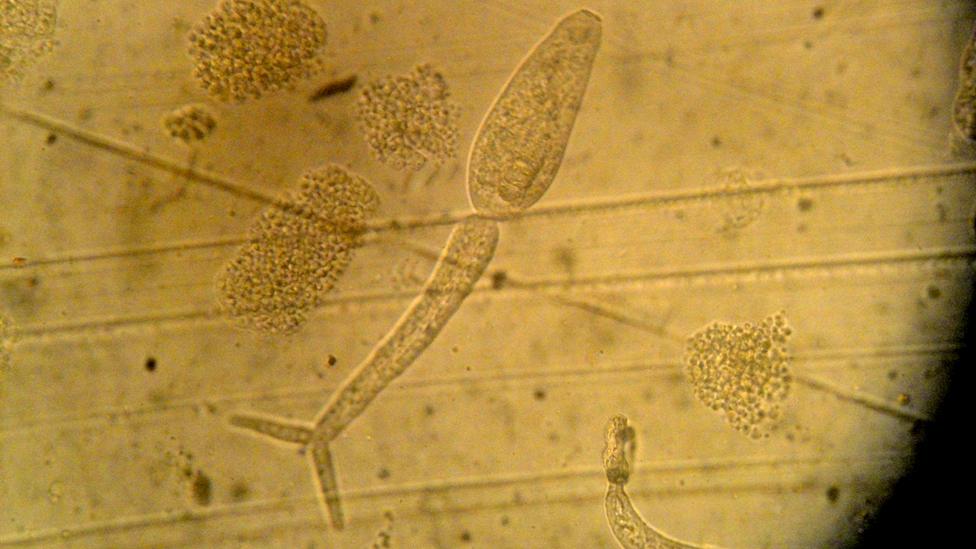

The disease is caused by parasitic worms, Schistosoma spp

In larval form, these parasites latch on to water snails

Once mature, they release into the river to infect humans

People get fever-like symptoms, abdominal pain, diarrhoea

Infection rates coincided with the loss of river prawns

Dams will hinder the crustaceans’s ability to reproduce

They are now working with various groups in Africa (the Upstream Alliance, external) to try to develop sustainable means of maintaining prawns in affected rivers.

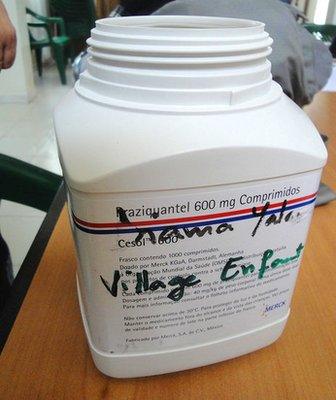

Praziquantel: A highly effective treatment but it does not stop re-infection

This includes prawn aquaculture farms. The crustaceans are corralled in netted areas close to the river bank to keep on top of the snails and then harvested for food. Schistosomiasis cannot be caught by eating the prawns, so it is a strategy that has economic as well as a health benefits.

The team is also examining the role other predators could play, such as catfish and ducks. Both will eat freshwater snails.

Another idea is to tackle the problem at source - the dam. It should be possible to retrofit barriers with some kind of prawn bypass, akin to the “ladders” that aid salmon in other parts of the world to get to their upstream spawning grounds.

The capital investment required at existing dams could be very large, however.

Giulio De Leo: "We want to identify other candidate sites around the world"

The native African prawn Macrobrachium vollenhovenii is the focus of attention and biotechnology (non GM) techniques are available that allow all-male progeny to be produced in aquaculture farms.

Using only males is preferable on a few counts. They grow fast and big and consume more snails, but being male they do not need to migrate in the same way as females, which require a saline estuary for spawning - so the dam becomes less of an issue.

But prawns are not a “silver bullet”, cautions Dr Sokolow. A suite of solutions will ultimately be necessary.

“There’s a drug treatment that works very well - praziquantel. It clears the worms out of people and is 98-99% effective. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have lasting effects, so people the very next day - people living in poverty, especially, where there isn’t clean and safe water to access - are back out in the rivers and streams getting re-infected," she told BBC News.

“Clearly, there are other factors in play, such as the building up of agricultural systems that follow the construction of the dams. That increases population densities and potentially puts agrochemicals in the river that influences the system. But when you add in the loss of the prawns, the situation becomes worse; and it suggests that this tool of restoring prawns could be a big factor in helping to reduce and mitigate the impact of dams on schistosomiasis.”

It may not be just prawns - ducks and catfish may be useful tools, also