Decoding Antarctica's response to a warming world

- Published

Ice giants of Antarctica: The Polarstern research vessel is almost 120m in length

A tangle of tubes, cables, and actuators - Mebo looks as though it could morph at any moment into one of those Transformer robots from the movies.

This was the seventh different ship from which MeBo has been deployed

The 10-tonne machine is in fact a seabed drilling system, and a very sophisticated one at that.

Deployed over the side of any large ship but driven remotely from onboard, it's opening up new opportunities to take sediment samples from the ocean floor.

MeBo was developed at the MARUM research facility, external in Bremen, Germany, and has not long returned from a pathfinding expedition to the West Antarctic.

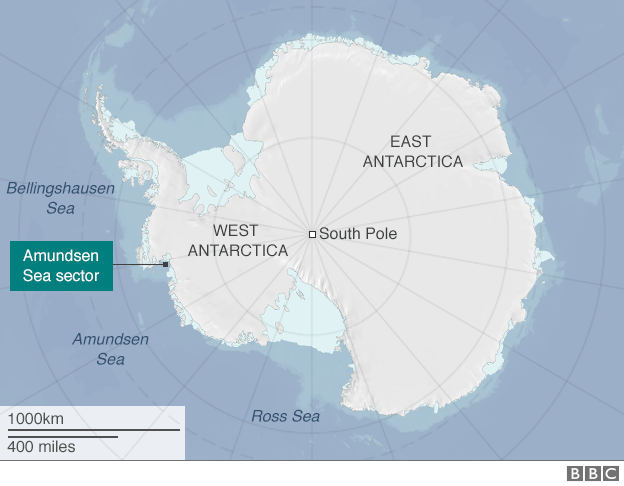

In the iceberg-infested waters of the Amundsen Sea Embayment (ASE), it obtained the very first cores to be drilled from just in front of some of the mightiest glaciers on Earth.

Chief among these are Pine Island Glacier and Thwaites Glacier, colossal streams of ice that drain the White Continent and which are now spilling mass into the ocean at an alarming rate.

There's concern that deep, warm water is undercutting the glaciers, possibly tipping them into an unstoppable retreat. And that has global implications for significant sea-level rise.

It was MeBo's job to help investigate whether this really could be happening.

MeBo Drilling System

An operator onboard the Polarstern directs MeBo's actions at the seabed

"Meeresboden-Bohrgerät" is German for "seafloor drill rig"

It's lowered to the seabed with a specially designed cable

This also delivers power, and carries commands and video

An operator drives MeBo remotely from the deployment ship

System has a magazine of pipes to lengthen the drill string

Mebo can penetrate mud and rock to a depth of up to 80m

Tim Freudenthal: "MeBo is a unique system that we've developed ourselves"

The goal was to retrieve seafloor sediments that would reveal the behaviour of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) in previous warm phases. To read the future in the past.

Karsten Gohl (L) inspects the cores as they come back up to the ship

"Has the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapsed before? Is that the scenario we should expect in the next couple of hundred years?" pondered project leader Karsten Gohl from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), external.

"Perhaps in some of these warm periods it has only partially collapsed, just a few portions of it. Or maybe the WAIS was hardly affected in those times. We hope we can understand this better by collecting samples because basically the sediments are a climate archive."

As glaciers grind their way off the continent they crush and bulldoze rock and drop it offshore. This material - the range of particles and their shapes, the way they are sorted, etc - codes the activity of the glaciers in the region.

Layers deposited during periods when the WAIS was extensive will contrast with those from times when glaciers were absent or significantly withdrawn.

"If you find ice-rafted debris (stones dropped by icebergs), for example, you can be sure there was ice on land and that the ice had advanced to the coast," explained Claus-Dieter Hillenbrand from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), external.

"But also new developments - especially what's known as geochemical provenance - have emerged in the last 10 years that mean it's even possible now to compare this material with rocks on land to pin down the actual sources in the hinterland."

Helpfully, nature also date-stamps the sediments by incorporating the remains of single-celled organisms (foraminifera and diatoms) from the ocean. The distinct species that lived through different epochs act as a fossil chronometer.

Back in Bremen: The cores have undergone CT scanning and have now been split open

MeBo's drill cores are now back in Bremen. A week ago, the cylindrical liners containing some 60m of ocean-floor material were being X-rayed at a local hospital to precisely determine their internal structure. And in the past few days, the task began of splitting the cores to allow their contents to be fully analysed.

The scientists who travelled to the Amundsen Sea with MeBo, on Germany's Polarstern research ship, already have some clues to what the cores will contain. They got a sneak preview in the rock and mud that was visible at the ends of the drill pipe segments when they were brought back up from below.

From the 11 locations MeBo sampled, it's very likely there are sediments that record the very deep past - from the Late Cretaceous, some 70 million years ago when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth and the landmass that is now Antarctica was green.

Karsten Gohl: "We're trying to reconstruct how the ice sheet behaved in the past"

Coming forward in time, it's probable also there are records from the Oligocene (34-23 million years ago) and the Miocene (23-5 million years ago) which should document some key events in Antarctica's history when a burgeoning ice sheet in the East of the continent was supplemented by one in the West.

"We haven't got a continuous sequence; we have spot samples from these different times," explained Dr Gohl. "But with these sediments we hope we can establish the onset of glaciation in Antarctica, and then get records from the time in the Miocene where in other areas of the Antarctic it's known there was the main glacial advance that has persisted to today."

With luck there are additional sediments distributed in the last few hundred thousand years, when WAIS glaciers would have advanced and retreated through the recent cycle of "ice ages".

Scientists got a preview of what to expect by looking at the ends of the drill pipe segments

What many scientists would dearly love to see is a rich record from the Pliocene, from a time three million years ago when carbon dioxide levels in Earth's atmosphere were very similar to what they are today (400 molecules of CO2 in every million molecules of dry air). WAIS behaviour at this time could represent the best analogue for what is about to happen to the ice sheet in the near future.

But this desire may have to wait to be satisfied by a second expedition with a dedicated drill ship, the Joides Resolution. The JR can bore hundreds of metres into the seabed, increasing the chances of capturing an unabridged view of the past. A firm booking has been made for 2019.

For now, researchers must work with the initial snapshot provided by MeBo. BAS team-member Bob Larter: "This is the first time we've had any real constraint on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, because although there's been a number of drilling exercises in the Ross Sea, it's hard from that location to know for sure whether the glacial signal is coming from the East or the West.

"Whereas if you drill in the Amundsen Sea, you know it's a record of the WAIS."

The results of the various lab analyses now under way are eagerly awaited and will be reported in a slew of scientific papers. For MeBo, the expedition has demonstrated once again what an agile system it is.

"This type of drilling will become more common, not just in science but also in industry," predicted Marum's Tim Freudenthal.

"There are several applications in the oil and mining industries, and offshore wind farms - they need geotechnical investigation of the seabed. For all these types of investigation, the big drilling vessels can often be too powerful. The seabed drilling systems like MeBo offer a very good alternative."

An update on the Amundsen Sea Embayment expedition was presented to the recent General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union, external (EGU).

Ice challenge: The drill system can only be lowered when big bergs are absent

To go ever deeper, MeBo selects additional drill pipes from a magazine

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published12 December 2016

- Published23 November 2016