James Webb: Swallowing the biggest space telescope

- Published

Juli Lander and Alberto Conti: "Chamber was built to test Apollo"

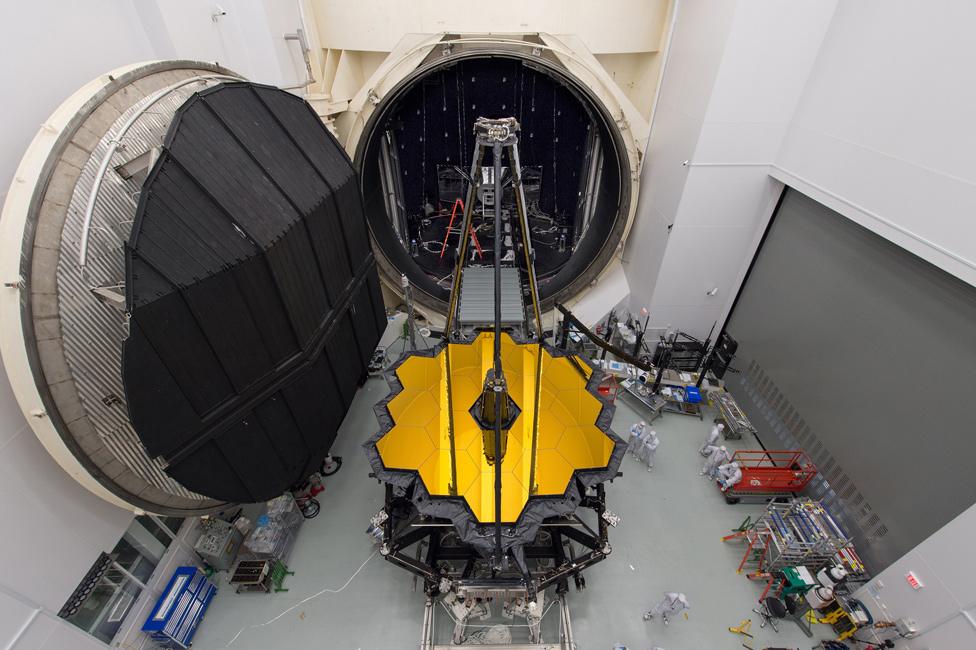

The door has closed on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The successor to Hubble has been locked tight inside a giant chamber where it will undergo a series of tests to simulate conditions off Earth.

Engineers must first pump out all the air, and then chill down the telescope to fantastically low temperatures.

In about 30 days' time, they should be ready to start the checks that ensure JWST, external's spectacular mirrors can focus light properly.

"The operational temperature on orbit is about 30 kelvins - 30 degrees above absolute zero; but we're going to test JWST to slightly lower," explains Juli Lander, a US space agency (Nasa) engineer on the project.

"We're going to see if we can push on the hardware and the instruments a bit to give us a little margin on orbit," she told BBC News.

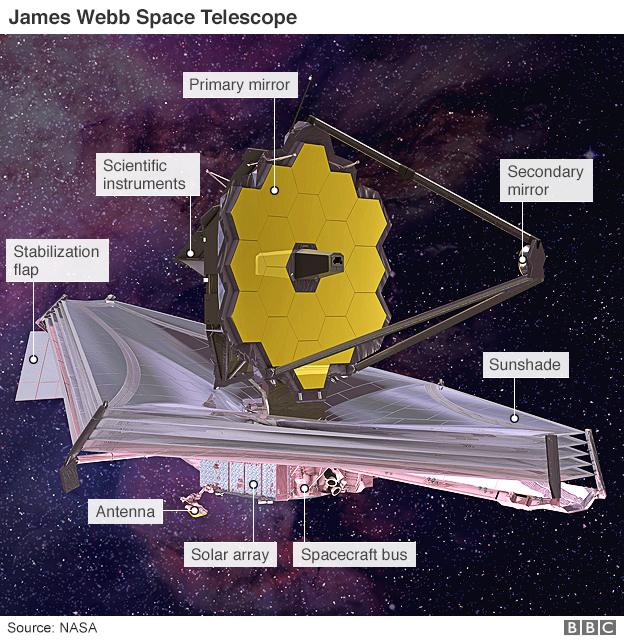

JWST is on track to be launched on a European Ariane rocket in just over a year from now. It will carry technologies capable of peering even deeper into space than Hubble - to detect the light coming from the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

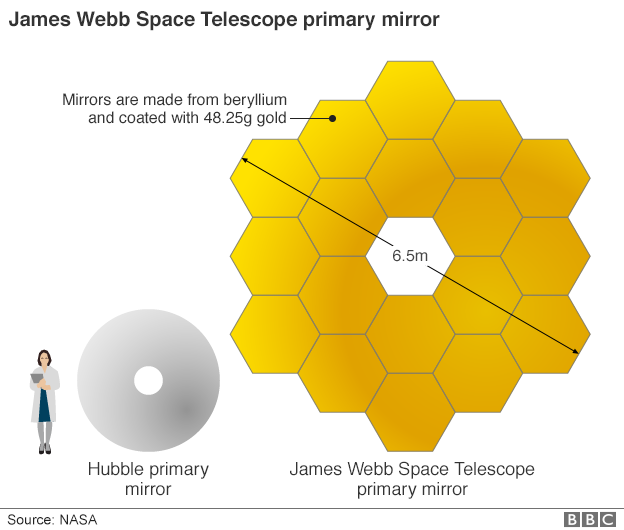

The shape of each mirror segment on Webb can be individually controlled

The development phase it has now entered at the Johnson Space Center in Texas is its final thermal-vacuum test; and this will confirm Webb does not have "a Hubble problem".

If you remember when the veteran space telescope first went into orbit in 1990, it had difficulty focussing images of the sky because its monolithic primary mirror was ever so slightly misshapen. Visiting astronauts had to fit corrective optics to the observatory - to, in effect, give Hubble a set of spectacles.

JWST is designed in such a way that the same mistake cannot be repeated - but the systems that should guarantee its perfect vision must first be demonstrated in the extreme conditions they will experience in space.

Lander explains: "One of the lessons from Hubble was if you have one big mirror then you could have a problem. Whereas on JWST, we have 18 separate mirror segments and each mirror has motors on the back that we can then align to make all the mirror segments perfectly in focus."

Fibre optics will feed light to different parts of the telescope to see how the mirrors bounce the signal into Webb's four instruments.

An important goal of the coming weeks is to calibrate all of the optical systems - to have a benchmark against which engineers can begin to understand and troubleshoot any anomalies that might occur when Webb is stationed at its observing position some 1.5 million km from Earth.

Once it fully gets going, the Johnson testing regime should last about a month. It will then take another month for the telescope to be brought back up to ambient conditions, to allow the door of the 17m-high chamber - built originally to run the rule over Apollo hardware - to be opened.

Webb's next destination is California and a satellite factory belonging to Northrop Grumman, external. The telescope still has to be attached to the spacecraft "bus" that will shepherd it in orbit - and to the colossal sunshield that will shade its delicate investigations of the distant Universe.

Northrop Grumman is the main industrial partner on the project, and its not-for-profit foundation has produced a film to explain the near three-decade effort that has gone into developing the biggest ever space telescope. It can be watched online, external.

Nasa engineers flip James Webb's mirror

One of its most amusing moments is when Nobel Prize winner and chief scientist John Mather considers whether Webb's optics could sense the heat energy of a bumblebee at a distant equivalent to that of the Moon. It could, he concludes: "You have to take a time exposure to get something that sensitive; the bumblebee shouldn't move. The bumblebee has to hold still, but of course the most distant Universe looks as though it is standing still."

Northrop Grumman astrophysicist Alberto Conti has been travelling through Europe to promote Webb with the film. He says he hopes the epic scale of the project will prompt many young people into a STEM profession.

"We need to show people that not only the science is cool but that it’s really inspiring. And every single bit counts," he told BBC News.

"It doesn’t matter if you're an engineer or a scientist trying to figure out how you can do it; you just want to excite a new generation. It takes a village, as they say; it takes a lot of people to build complex machines like this."

The James Webb Space Telescope is a joint endeavour between the US, European and Canadian space agencies.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external