Cassini skims Saturn's atmosphere

- Published

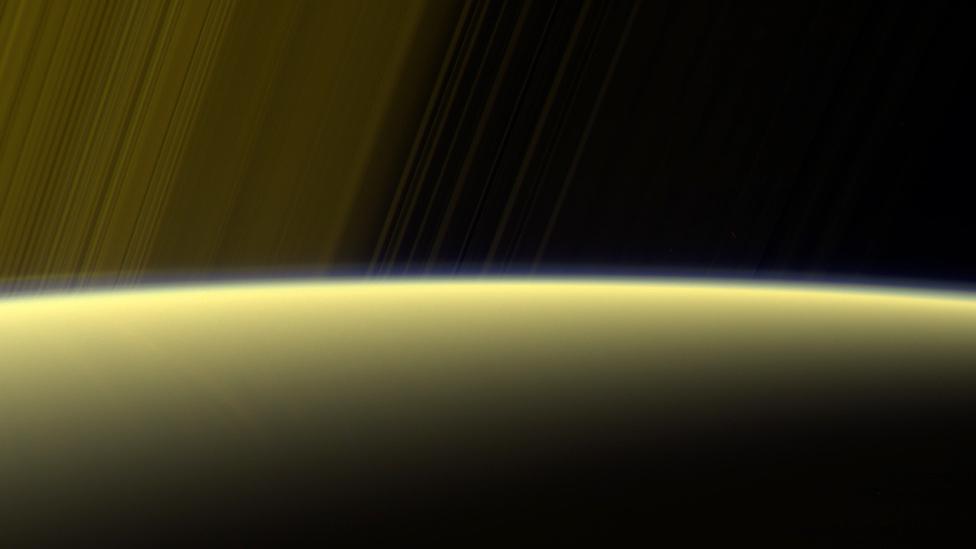

Cassini will "dip its toes" into the atmosphere during the final passes

The Cassini probe has begun the final phase of its mission to Saturn.

The satellite has executed the first of five ultra-close passes of the giant world, dipping down far enough to brush through the top of the atmosphere.

It promises unprecedented data on the chemical composition of Saturn.

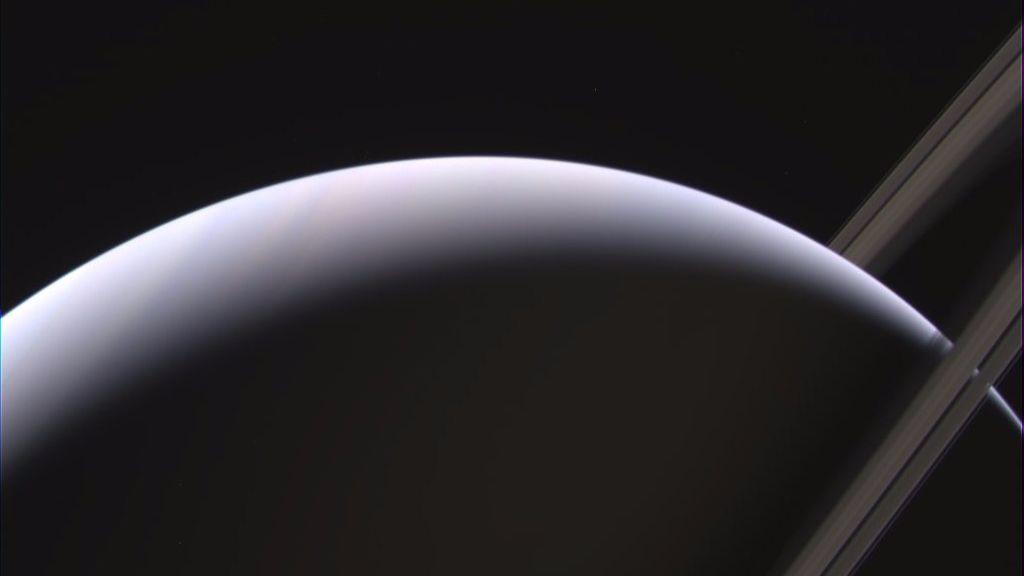

It also sets the stage for the probe's dramatic end-manoeuvre next month when it will plunge to destruction in the planet's atmosphere.

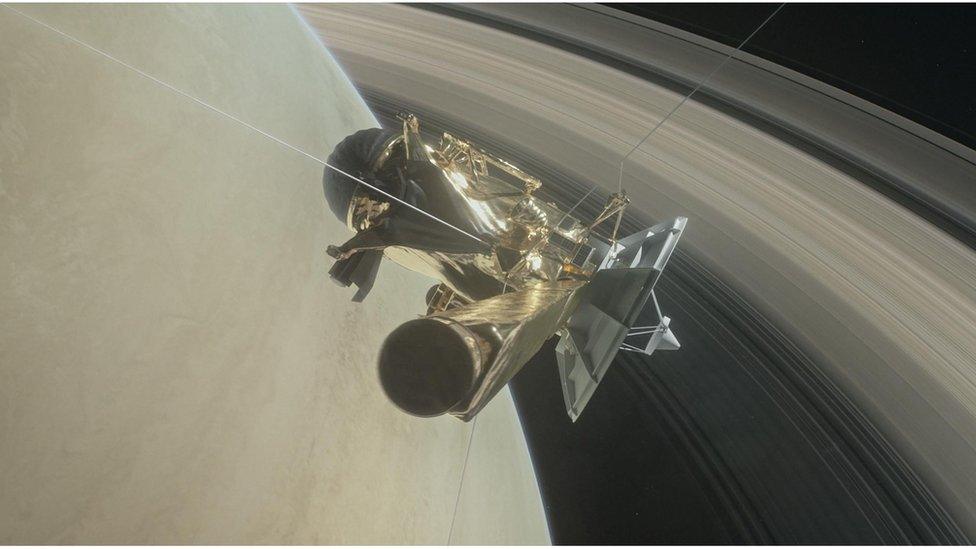

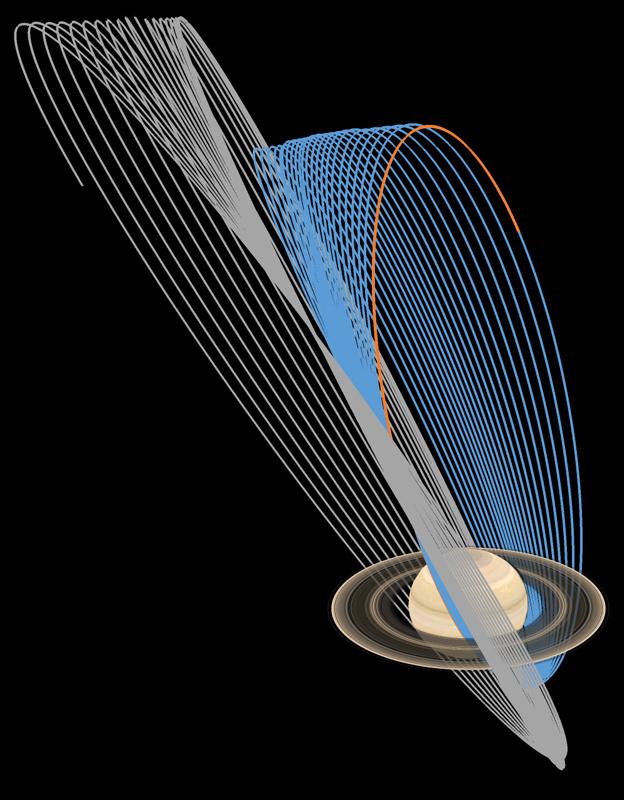

Cassini is currently flying a series of loops around Saturn that thread the gap between its atmosphere and its rings.

Monday's swing-by saw the spacecraft go closer than ever before to the cloud tops - skimming just 1,600km (1,000 miles) above them, at 04:22 GMT (05:22 BST) on Monday.

This low pass was designed to allow the probe to directly sample the gases of the extended upper-atmosphere.

Saturn's bulk composition is thought to be about 75% hydrogen with the rest being helium (bar some trace components), explains Nicolas Altobelli, the European Space Agency's Cassini project scientist.

"It's expected that the heavier helium is sinking down," he told BBC News. "Saturn radiates more energy than it's absorbing from the Sun, meaning there's gravitational energy which is being lost. And so getting a precise measure of the hydrogen and helium in the upper layers sets a constraint on the overall distribution of the material in the interior."

Cassini will send all the data back to Earth during its next contact on Tuesday.

Dipping down into the atmosphere should create a drag on the spacecraft, requiring Cassini to use its thrusters to maintain a stable flight configuration and stop itself from tumbling. But the mission's scientists think any buffeting effects ought to be manageable.

They are hopeful that when the post-pass analysis is done, the probe will be permitted to go even lower on the remaining four dip-downs before 15 September's goodbye plunge.

Artwork: Cassini is running the narrow gap between the top of the planet's atmosphere and the rings

The Cassini mission still has some big outstanding questions about Saturn. One of these relates to the length of a day on the planet.

Researchers know it is roughly 10-and-a-half hours, but they would like a more precise number.

The solution should come by looking for an offset between the magnetic field and the planet's rotation axis, but frustratingly all the probe's observations to date show these two features to be almost perfectly aligned.

"All magnetic field theory as we know it requires an offset," said Linda Spilker, the US space agency's Cassini project scientist.

"To generate a field, you need to keep the currents in the metallic hydrogen layer inside Saturn flowing, and without the offset the thinking is that the field would simply go away.

"What's going on? Is something shielding our ability to see the offset, or do we simply need a new theory? But without the tilt, without being able to see the tiny wobble, we cannot be more precise about the length of a day."

Dr Spilker said the mission team would continue to work on the problem.

Cassini is a joint venture between the US, European and Italian space agencies. They are ending the probe's operations after 20 years because it is running low on fuel and will soon become uncontrollable.

Scientists want to avoid the possibility of a future collision with Saturn's moons Titan and Enceladus, which could conceivably support simple microbial life. And the only way to prevent that is to deliberately drive the probe to destruction in the atmosphere of the giant planet.

Cassini's final orbits (blue) take the probe closer to the planet than it has ever been before

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 May 2017

- Published27 April 2017