Cassini hints at young age for Saturn's rings

- Published

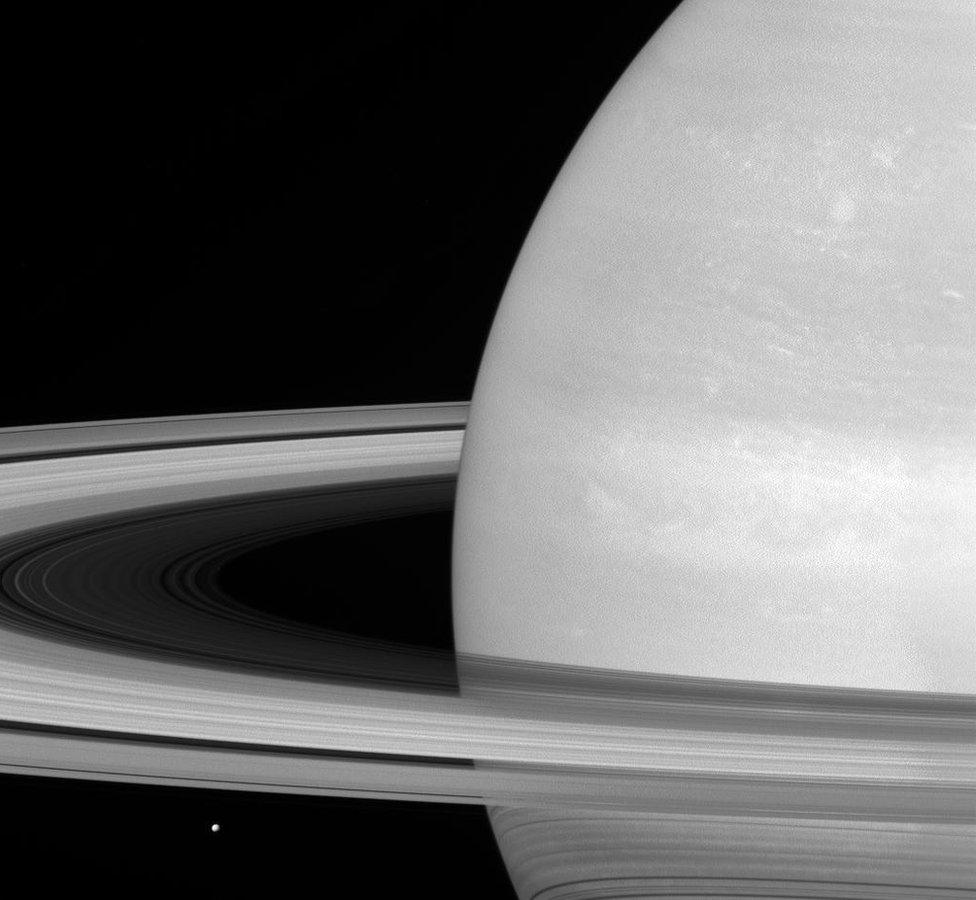

Cassini has been trying to weigh the rings

The spectacular rings of Saturn may be relatively young, perhaps just 100 million years or so old.

This is the early interpretation of data gathered by the Cassini spacecraft on its final orbits of the giant world.

If confirmed, it means we are looking at Saturn at a very special time in the age of the Solar System.

Cassini is scheduled to make only two more close-in passes before driving itself to destruction in Saturn's atmosphere on 15 September.

The probe is being disposed of in this way because it will soon run out of fuel. That would render it uncontrollable, and mission managers at the US space agency Nasa do not want it crashing into - and contaminating - moons that could conceivably host microbial lifeforms.

The approaching end means scientists and engineers are now taking risks with Cassini that would never have been contemplated when the probe arrived at the planet 13 years ago.

Chief among these risks are the dramatic flybys Cassini undertakes every six days. These see the spacecraft plunge through the gap between the top of Saturn's atmosphere and the rings. It is a completely unexplored region from where Cassini is returning some unique data.

This includes making a detailed map of the gravity field in which the contributions from the huge world and the rings can be teased apart.

Cassini is essentially trying to weigh the rings. Their mass says something about their age.

The more massive they are, the older they are likely to be. Some scientists think they could even have formed with Saturn itself 4.6 billion years ago. They would certainly need a large mass to withstand the forces that might erode them over time, such as collisions from tiny meteoroids. But it is looking like the opposite may actually be true - that their mass is less than previously estimated.

If confirmed it points to the rings being the remnants of some object that has broken apart around Saturn in the recent past.

"For younger rings, it would require a comet, or a centaur (one of a group of small, icy objects), or perhaps even a moon moving too close to Saturn. Saturn's gravity would break apart that object and then the remaining bits would go on to form rings," explained Linda Spilker, Nasa's Cassini project scientist.

"Perhaps that's happened more than once. Maybe some of the differences we see in the rings are from different objects that were broken apart. But if the rings are less massive they won't have had the mass to survive the micro-meteoroid bombardment that we estimate to have happened since the formation of the planet.

"So, we're heading in the direction of the rings being perhaps 100 million years old or so, which is quite young compared to the age of the Solar System," she told BBC News.

Dr Spilker did however caution that these were early days in the analysis of the new data and the uncertainties were still large.

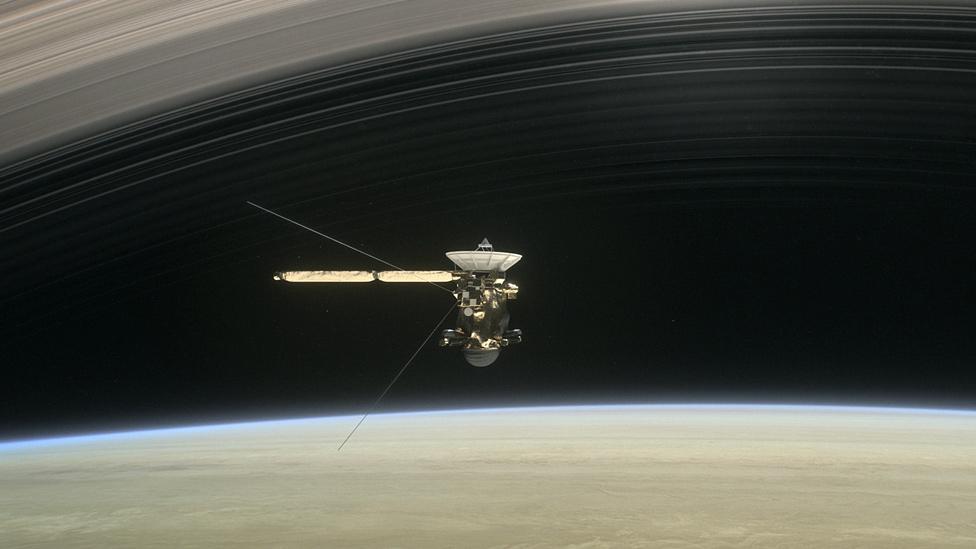

Artwork: Cassini is currently running the narrow gap between the top of the planet's atmosphere and the rings

Other team members have been outlining plans for the remaining 18 days of the mission.

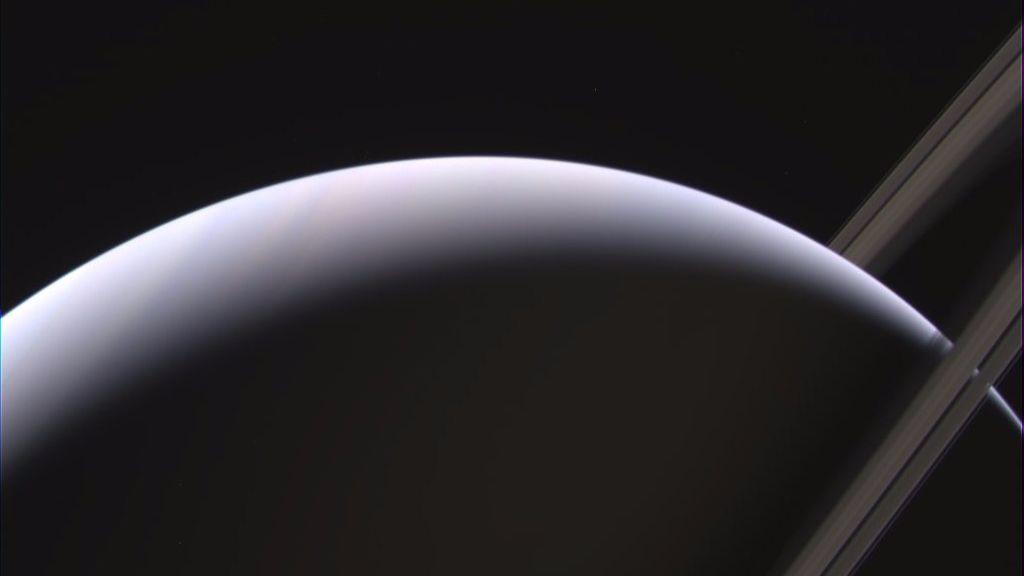

Cassini will take its final images on Thursday 14 September - "What we're calling the 'Last Picture Show'; the final set of images of some of the selected targets of the Saturn system," said Earl Maize, Nasa's Cassini project manager.

These include pictures of the moons Titan and Enceladus, the strange hexagon-shaped jet stream at the planet's north pole, and the little moonlet embedded in the rings known as Peggy.

The spacecraft will then be reconfigured for its death plunge. This means prioritising those instruments that can gather atmospheric data.

Cassini will melt and be torn apart as it dives into the planet's gases at over 120,000km/h. Controllers will know the probe has been destroyed when Earth antennas lose radio contact, which is expected to occur at 11:54 GMT (12:54 BST; 07:54 EDT; 04:54 PDT) on Friday 15 September.

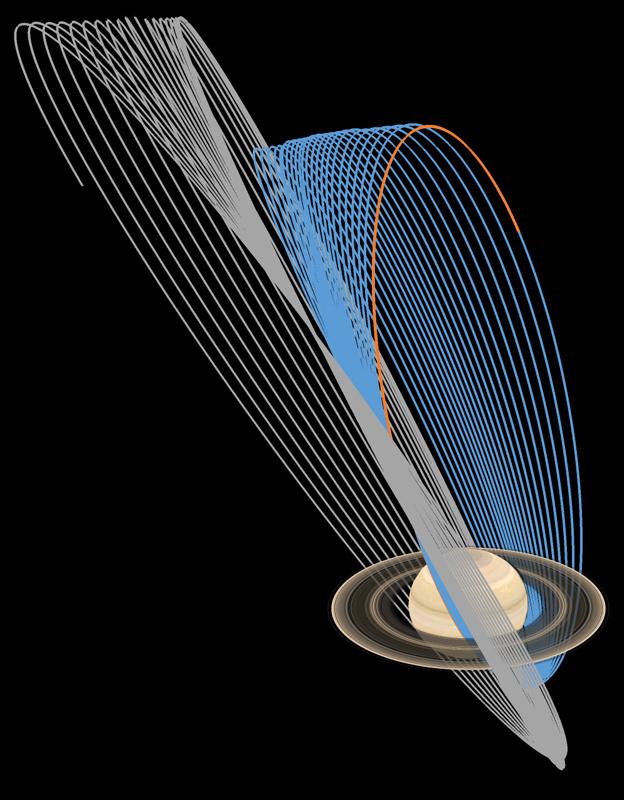

Cassini's final orbits (blue) take the probe closer to the planet than it has ever been before

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published2 May 2017

- Published27 April 2017