Ozone layer recovery could be delayed by 30 years

- Published

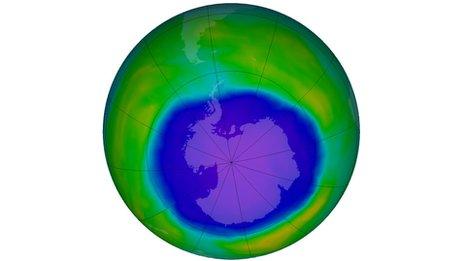

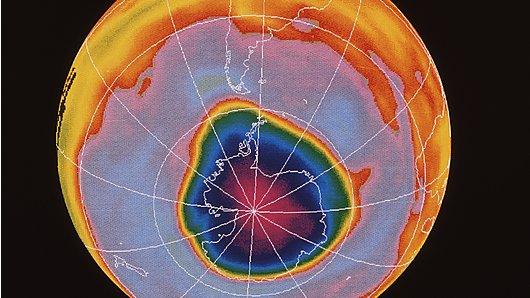

Researchers reported in 2015 that there was clear evidence of healing in the ozone hole

Rising global emissions of some chlorine-containing chemicals could slow the progress made in healing the ozone layer.

A study found the substances, widely used for paint stripping and in the manufacture of PVC, are increasing much faster than previously thought.

Mainly produced in China, these compounds are not currently regulated.

Experts say their continued use could set back the closing of the ozone hole by up to 30 years.

Scientists reported last year that they had detected the first clear evidence that the thinning of the protective ozone layer was diminishing.

The visualisation runs from January to December 2016

The Montreal Protocol, which was signed 30 years ago, was the key to this progress. It has progressively helped governments phase out the chlorofluorocarbons and the hydrochlorofluorocarbons that were causing the problem.

However, concern has been growing over the past few years about a number of chemicals, dubbed "very short-lived substances".

Dichloromethane is one of these chemicals, and is used as an industrial solvent and a paint remover. Levels in the atmosphere have increased by 60% over the past decade.

Another compound highlighted in this new report is dichloroethane. It's used in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride or PVC, a light plastic widely used in construction, agriculture and elsewhere.

For a long time, scientists believed that both these compounds would decay before getting up as far as the ozone layer.

However, air samples analysed in this new study suggest this view may be mistaken and these destructive elements are getting there quicker and doing more damage than thought.

A boom in the use of PVC for agriculture and construction is part of the problem

The authors found that cold wind blows these chemicals from factories in China to the eastern Pacific. This is one of the main locations where air gets uplifted into the stratosphere.

"Our aircraft samples show the path from emissions in China, through the tropics in Malaysia and up to about 12km in the atmosphere," said lead author Dr David Oram from the University of East Anglia.

"This implies a route whereby these short-lived compounds can get into the atmosphere much quicker than if they had been released in North America or Manchester."

What is surprising for the scientists is that both these compounds are valuable and also toxic to workers, so there is every incentive for producers to ensure there is no leakage.

However, the new study suggests that leaks and fugitive emissions are occurring and at rates which could have serious implications for the ozone layer.

"We believe that if we carry on with these emissions we'll delay the recovery of the layer," said Dr Oram.

"At the moment an average date for ozone recovery could be about 2050 but there are studies that say this could be delayed by 20-30 years depending on future emissions of things like dichloromethane."

The researchers say that a building boom in India is a concern as that will likely see a rise in the amounts of PVC being used with a knock-on effect on levels of dichloroethane in the air.

The Bachok air sampling site in Malaysia where samples used in this study were captured

Other scientists in this field are also concerned about the rise of these unregulated substances.

"Short lived chlorocarbons have been generally overlooked in terms of ozone loss in recent years," said Dr David Rowley from University College London, who wasn't involved in the study.

"This was wrong as they affect lower atmospheric ozone (and therefore oxidising capacity, the ability of the air to remove pollutants), but they can also be transported to the stratosphere through deep convective events, where they can destroy ozone really effectively."

However, some researchers are not convinced that the new study shows the compounds getting into the exact part of the atmosphere where damage to the ozone layer can be done.

"The measurements report dichloromethane at an altitude of 10-12km - this is still the troposphere," said Dr Susan Strahan from Nasa.

"To demonstrate that it is a threat to ozone requires measurements of dichloromethane in the tropical lower stratosphere.

"In the additional weeks required to travel to the lower stratosphere, which is above 16km, even more of the compound will be destroyed."

Despite these reservations, the authors of the new study are calling for policy makers to extend the remit of the Montreal Protocol to cover these very short-lived substances.

The new paper has been published, external in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics.

Follow Matt on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external.

- Published30 June 2016

- Published26 May 2015

- Published12 December 2013