Antarctic glacier's rough belly exposed

- Published

This movie illustrates the rough terrain underlying some parts of the PIG

The melting Antarctic ice stream that is currently adding most to sea-level rise may be more resilient to change than previously recognised.

New radar images reveal the mighty Pine Island Glacier (PIG) to be sitting on a rugged rock bed populated by big hills, tall cliffs and deep scour marks.

Such features are likely to slow the ice body’s retreat as the climate warms, researchers say.

The study appears in the journal Nature Communications, external.

"We've imaged the shape of the bed at a smaller scale than ever before and the message is really quite profound for the ice flow and potentially for the retreat of the glacier," said lead author Dr Rob Bingham from Edinburgh University.

"Where the bed is flat - that’s where we will see major retreat. But where we see these large hills and these other rough features - that’s where we may see the retreat slowed if not stemmed," he told BBC News.

For weeks, the team dragged radar equipment across the glacier surface

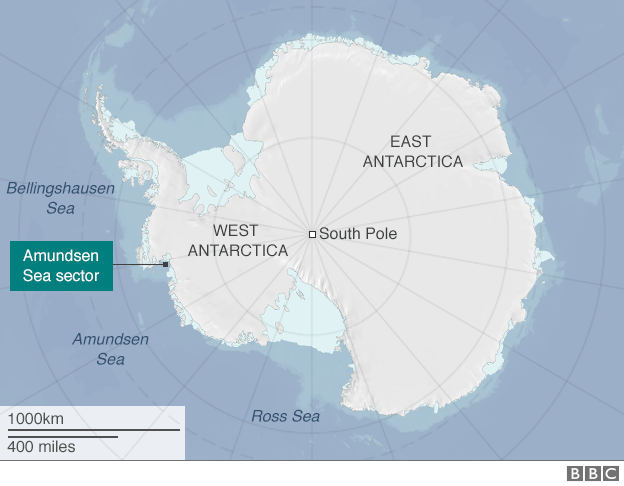

The PIG is a vast feature in West Antarctica.

The glacier runs alongside the Hudson mountains into the Amundsen Sea, draining an area covering more than 160,000 sq km - about two-thirds the size of the UK.

Its remoteness makes it extremely difficult to study, and it is only in the past 20 years or so, with the aid of satellites, that scientists have realised the glacier is undergoing significant change.

The PIG has sped up and thinned as warmer ocean waters have got under its floating front to melt the ice from below.

The grounding line - the point where this front starts to become buoyant - has pulled back towards the land by more than 30km since the early 1990s, leading some researchers to believe the whole glacier could collapse within a few hundred years if global warming accelerates matters.

But to have real confidence in modelling its future behaviour, scientists need to know far more about the PIG.

In particular, they need to understand better the type of ground over which the ice is sliding.

It is this type of data that is now being reported by the British team, who dragged radar instruments over the glacier in a weeks-long campaign in the southern summer of 2013/14.

Radar can see through hundreds of metres of ice to sense the topography at the base of the glacier. And although the expedition could not map the PIG’s full extent, sampling was done at key places on the main flowing trunk and the major tributaries. A total of 1,500 sq km was imaged.

What was expected was that the basal rock would show lineations from the scouring effects of ice that has been moving across it for millions of years.

What was unexpected though was the scale of the relief seen in a number of areas.

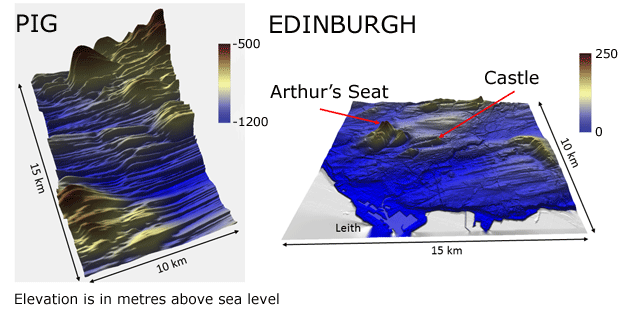

The classic lineations ground by flowing ice are evident both at the base of the PIG and around the city of Edinburgh. But surprisingly, the glacier's bed has examples of very jagged terrain even though the ice has been passing across it for millions of years.

To illustrate this roughness, the team has produced a comparison of the PIG’s underbelly with the glacial terrain surrounding Edinburgh.

The Scottish capital was itself covered by an ice sheet 20,000 years ago.

The famous elevations of Arthur’s Seat and Castle Rock look puny next to some of the jagged features underlying the PIG.

"In one place at the bed of Pine Island, the ice mounts a cliff that's almost vertical and some 400m high," explained Dr Bingham.

"This would be a totally incredible feature if you could stand in front of it and see it for yourself. But it's buried deep under the ice. At the surface of the glacier, of course, you wouldn’t even know that it's down there because the top of the PIG is so flat."

The surface of the PIG may be flat but the radar technology senses the hidden topography

The Edinburgh scientist believes the rock under the glacier must be extremely hard to have retained such roughness.

Co-author Prof David Vaughan, from the British Antarctic Survey, says the new information will now bring greater refinement to ice models.

"The extra roughness beneath Pine Island Glacier is significant because at the moment we model the glacier in a way that puts everything we know about the bed into a single parameter which we 'infer'.

"This research begins the process of measuring those bed properties in a much more correct and more robust way,” he told BBC News.

The PIG research was conducted under a programme called iSTAR. A similar effort will now target the "next door" Thwaites Glacier. This also is shedding billions of tonnes of ice each year that contribute to rising sea levels.