Mysterious rise in emissions of ozone-damaging chemical

- Published

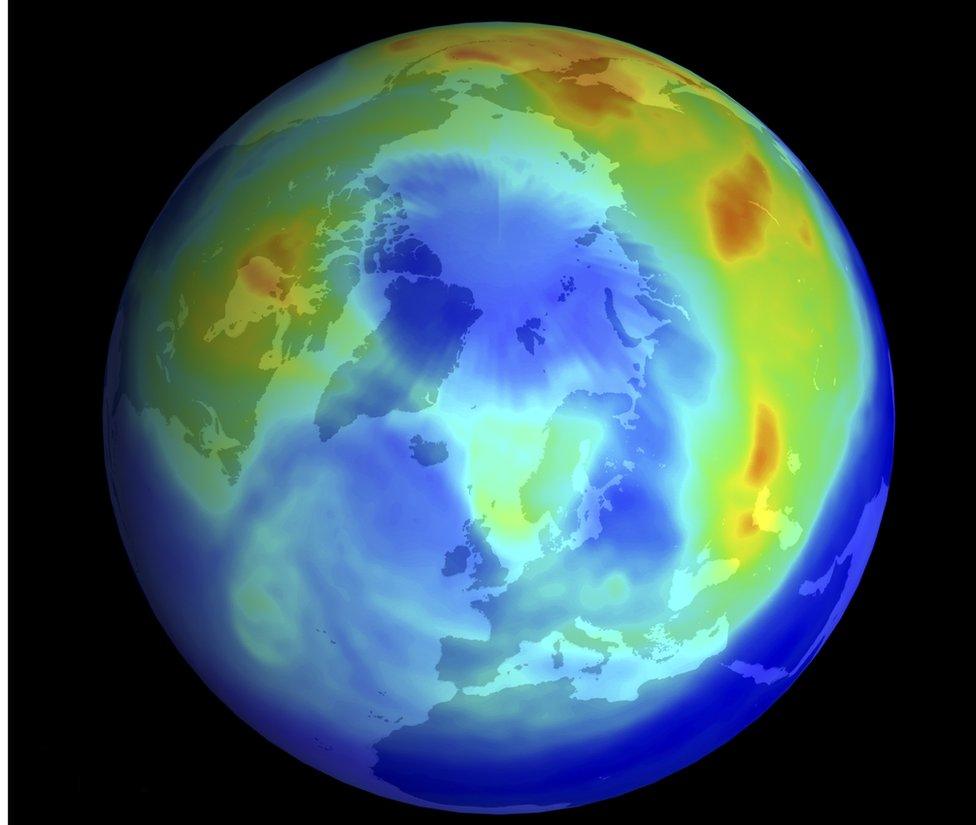

Ozone depletion over the Arctic has been much less pronounced than over the Antarctic

Scientists have detected an unexpected rise in atmospheric levels of CFC-11, a chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) highly damaging to the ozone layer.

Banned by the Montreal Protocol in 1987, CFC-11 was seen to be declining as expected but that fall has slowed down by 50% since 2012.

Researchers say their evidence shows it's likely that new, illegal emissions of CFC-11 are coming from East Asia.

These could hamper the recovery of the ozone hole and worsen climate change.

CFC-11 is also known as trichlorofluoromethane, and is one of a number of CFCs that were initially developed as refrigerants during the 1930s.

They were also used as propellants in aerosol sprays and in solvents.

However, it took many decades for scientists to discover that when CFCs break down in the atmosphere, they release chlorine atoms that are able to rapidly destroy ozone molecules.

The finding that the destruction of ozone was creating a large "hole" over the Antarctic led to the signing of the Montreal Protocol in 1987.

This treaty saw the production of CFCs, including CFC-11, banned in developed countries in the mid 1990s and in the rest of the world by 2010.

As production stalled, existing reservoirs of the chemicals were expected to gradually escape to the atmosphere and diminish.

Scientists have been carefully gathering data from air monitoring stations around the world ever since to make sure everything is progressing as anticipated.

And so successful has Montreal been that scientists have spoken of a recovery being under way.

But there a growing scientific doubts about the progress of healing in the ozone hole. Reports last year indicated that production of new chlorine-containing chemicals could cause significant delay.

The new study published on Wednesday shows that, as expected, the rate of decline of concentrations of CFC-11 observed was constant between 2002 and 2012. However, since 2012, this decline has slowed by around 50%.

The authors of the new report discount the idea that this change could be due to releases from existing stores, emissions from older buildings being decommissioned, or from the accidental production of CFC-11 as a by-product of other chemical manufacture.

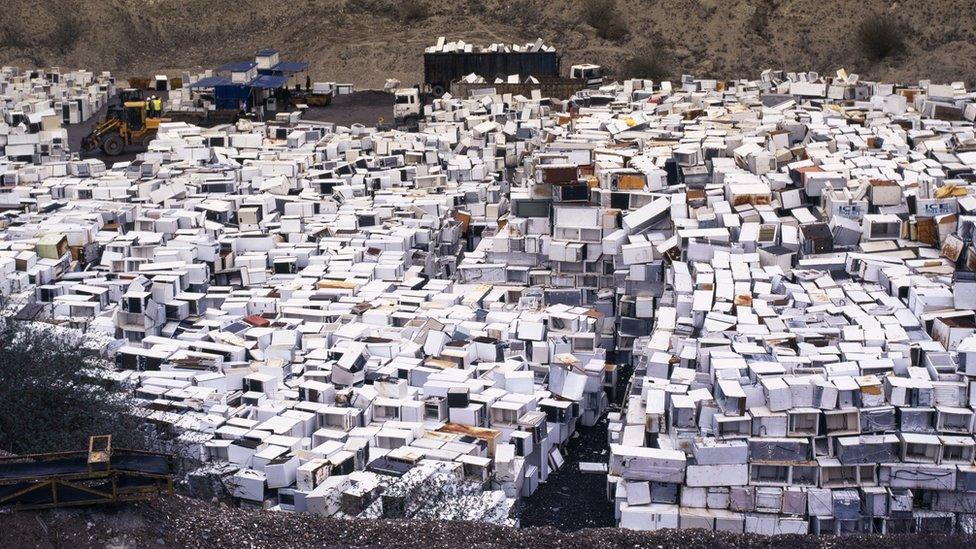

Older fridges are more likely to contain compounds that will damage the ozone layer

In 2013, plumes of air containing elevated levels of CFC-11 were detected at the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii.

The authors of this research say it's likely that illegal production of CFC-11 in East Asia is behind the rise.

"They do point in that direction, fairly definitively," Dr Stephen Montzka from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) told BBC News.

"We are making the measurements from very far away from these regions and I think more specificity is going to come once the people... in that region...look carefully at their measurements and publish their results," he added.

"Any production of an ozone-depleting gas that's controlled by the Montreal Protocol has to be reported to the ozone secretariat, and, currently, global production is essentially zero. We know of no production even for intermediary or side products."

The researchers are puzzled as to what the motivation for any unauthorised new production might be.

They point to the fact that since the production of these chemicals was ended over eight years ago, any industry that was involved in this work would have transitioned to other substances.

"It's disappointing, I would not have expected it to happen," said Dr Michaela Hegglin from Reading University, UK, who was not involved in the study.

"The newer substances that are out there, the replacements for CFC-11, might be more difficult or expensive for some countries to produce or get at.

"I hope that somehow the international community can put pressure on South East Asian countries, maybe China, to go and look at whether they can get more information on where the emissions come from. They should tell the industries that's not going to work."

The study authors point out that while CFC-11 can persist in the atmosphere for 50 years, the overall level of chlorine atoms is still declining.

However, if no action is taken on the new source of emissions, it could be highly significant.

"If the emissions were to persist, then we could imagine that healing of the ozone layer, that recovery date, could be delayed by a decade," said Dr Montzka.

It could also make a contribution to rising global temperatures.

The researchers say that the study also shows that early warning air monitoring systems are an essential element to police emissions of ozone damaging chemicals going forward as countries agreed on further, significant phase outs in

With the international community agreeing further, significant phase-outs in Kigali, in 2016, the researchers say early-warning, air-monitoring systems will be an essential part of the future policing of emissions.