InSight: Nasa's Mars mission on target for landing

- Published

Artwork: It takes 6.5 minutes to go from the top of the atmosphere to the surface

The American space agency Nasa says its InSight Mars lander is on a near-perfect Thanksgiving trajectory.

The probe is due to touch down on Monday at 19:53 GMT, to begin its quest to map the Red Planet's interior.

Engineers can take the opportunity for one last course correction on Sunday to tighten the line to the bulls-eye - but they may not bother with it.

"Right now we're looking really good, and we might be able to skip it," said Nasa's Tom Hoffman.

"We'll be working on the final parameters we need over the next few days, so while everybody's off having turkey, there'll be a bunch of people at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) making sure we land successfully," the InSight project manager told reporters.

JPL in Pasadena, California, is mission control for all Nasa's planetary adventures.

InSight, which launched from Earth on 5 May, has to hit a "keyhole" at the top of Mars' atmosphere that measures just 24km by 10km. If it can do that - and everything at present suggests it will - then it ought to come down right on top of a very flat landscape known as Elysium Planitia.

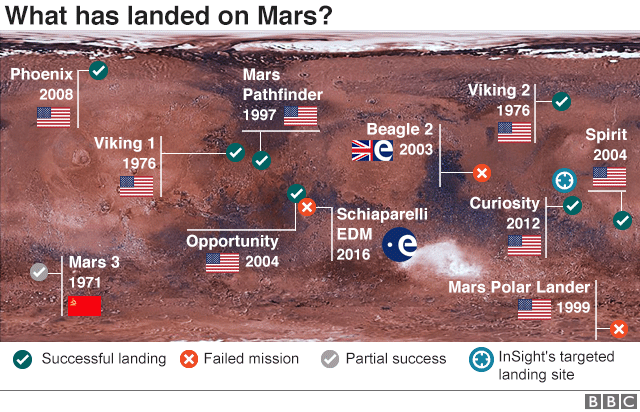

The task of atmospheric entry, descent and landing (EDL) is far from straightforward, however. Mission statistics show Mars to be unforgiving to the ill-prepared. Two-thirds of all landing attempts have failed.

The reason is simple: A probe will enter the atmosphere at six times the speed of a high-velocity bullet and then somehow have to slow to a controlled stop at the surface - all inside seven minutes. An EDL strategy has to be perfect.

The most recent effort in 2016 - from Europe - got it hopelessly wrong and slammed into the ground.

The Americans, though, have a pretty good record, and InSight will use the proven combination of a heat-resistant capsule, a parachute and rockets to make its drop to Mars.

Julie Wertz-Chen is part of the InSight EDL team: "We've done everything we can to try and be successful but it's a really, really difficult thing to do, to land on another planet. We never want to go into it saying 'Oh yeah, no problem, this will work easily!', because you just never know what Mars will throw at you."

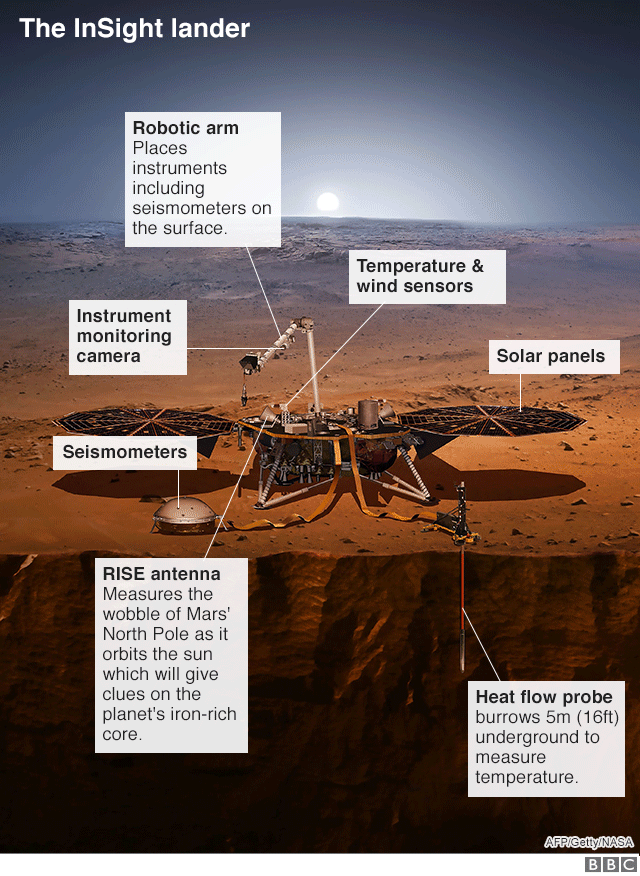

InSight aims to be the first mission to take a detailed look inside the Red Planet. It will use British and French seismometers to listen for earthquakes, or rather "Marsquakes".

These vibrations will help trace the interior rock layers - from the crust to the core.

"An earthquake is almost like a little flashbulb," explains InSight chief scientist Bruce Banerdt. "It illuminates the inside of the planet with seismic waves, and the seismometer is like a camera that picks up those waves and helps put together a picture. Pixel by pixel we get to put together a 3D picture of the inside of a planet."

Scientists know very well how Earth's interior is structured, and they have some good models to describe the initiation of this architecture at the Solar System's birth more than 4.5 billion years ago. But Earth is one data point and Mars will give researchers a different perspective on how a rocky planet can be assembled and evolve through time.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external