'Digital museum' brings millions of fossils out of the dark

- Published

Museums including Washington’s Smithsonian have set out to digitally record fossils in their collection

The bid to create a "global digital museum" has been welcomed by scientists, who say it will enable them to study valuable specimens that are currently "hidden" in museum drawers.

Museums including London's Natural History Museum, external and the Smithsonian in Washington DC, external are involved.

They have set out ambitious plans to digitise millions of specimens.

Digitally recording the 40 million fossils at the Smithsonian will take an estimated 50 years.

But five years into the project, the team says it is "bringing dark data into the light" for crucial research.

What is digitisation?

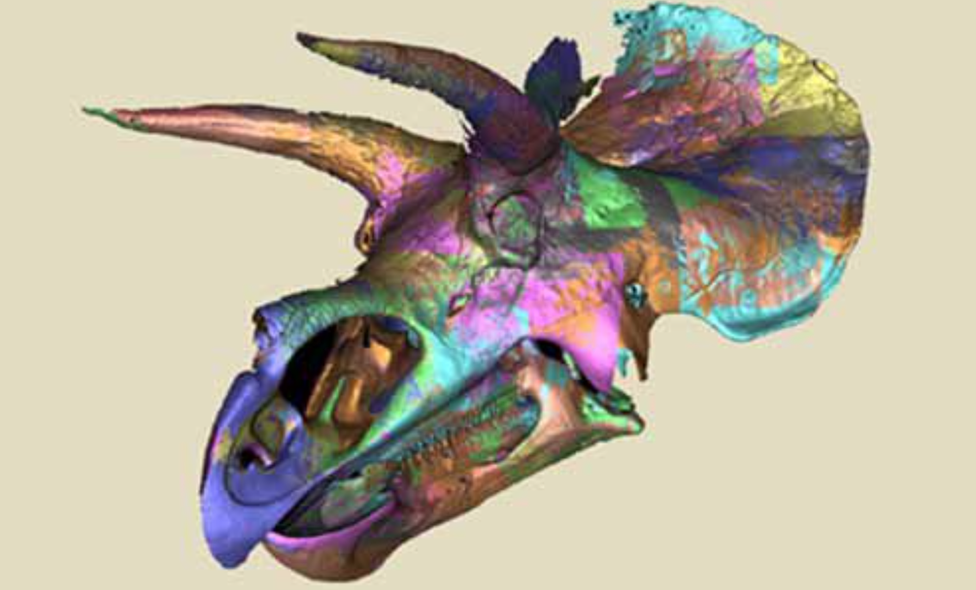

The skull of Triceratops has been CT-scanned

Kathy Hollis from the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, who is leading the project there, explained: "We are trying to make our entire collection available digitally for researchers to use online from anywhere in the world.

"And we're pretty sure that this is the largest fossil collection in the world.

"We have over 40 million specimens in the collection - it records the entire history of life, so if it has a fossil representative, it's likely here within the collection."

Items on public display in museums represent only a tiny fraction of the collections stored away in drawers.

"And there are drawers here in the museum that haven't been opened for decades," said Kathy Hollis.

That is problematic if scientists want to use all of those specimens - the collective evidence of millions of years of evolution on our planet - to understand how life works and changes.

"So we're bringing all of this data out into the light for research," she added.

In a recent paper in the Royal Society journal Biology Letters, scientists described the process of digitising museum collections as mobilising "dark data", external. The authors said this would enhance researchers' ability to understand how our environment changed in the past and therefore to build a picture of the impact of future environmental change.

Can a digital fossil ever be as useful as the real thing?

In some cases, it is far more useful.

Digitally recording 40 million fossils in the Smithsonian collection will take an estimated 50 years

For the vast majority of the digitisation project, museums will capture high quality images and all of the key information - age, species, where the specimen was discovered - to make available online.

That alone is valuable - studying digital marine fossils, for example, is already enabling researchers to understand how marine life in changing sea levels and ocean temperatures.

But the most detailed digital data can actually be better than a real fossil.

Prof Emily Rayfield at the University of Bristol uses CT scans of dinosaur skulls and other bones to build computer models for research.

"We can actually use the digital data to test how these animals functioned," she told BBC News.

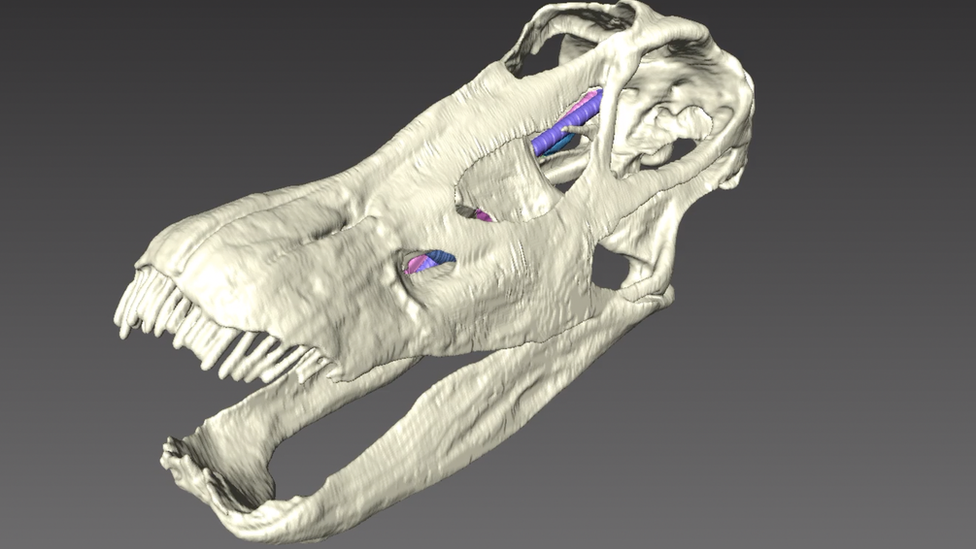

A digital diplodocus skull can be tested with software that reveals how the animal moved and ate

While it would be difficult even to lift the real, fragile, fossilised skull of diplodocus, for example, Prof Rayfield is able to twist, turn, compress and stress her digital dinosaur bones to reveal how the animals would have moved, what they ate and how they interacted with their environment.

This helped her and her colleagues to solve one the great puzzles about the sauropods - the small-headed, huge bodied dinosaurs in the same related group as the famous diplodocus.

"People have wondered how an environment could possibly have supported and provided food for so many multi-tonne, plant-eating giants," she explained.

"One of the ideas has been that the differences in the neck length, the skull shape and the tooth shape enabled them to feed on different things.

"One of my students has been able to use the digital data to test this idea."

This essentially meant rebuilding each digital dinosaur's jaw muscles and testing how it bit and chewed.

"This showed that the different types of sauropods were indeed feeding in different ways and therefore probably on different types of food, which enabled the environment to sustain so many of these 10-plus tonne dinosaurs at once."

Prof Rayfield's colleague at Bristol University, Prof Philip Donoghue, uses digital scans of ancient, fossilised microorganisms to produce large-scale versions that reveal far more detail about how the they lived.

He told BBC News that a digital fossil would transform scientists' ability to study life on Earth.

"We need to ensure though," he added "that a digital museum is properly and consistently recorded and curated, so that the data is of the highest possible quality."

The destruction of the Brazil National Museum in 2018 underscored the importance of digital collections

The BBC's Victoria Gill, external and Jonathan Amos, external are in Washington DC covering the annual American Geophysical Union, external meeting, the largest gathering of Earth and space scientists in the world.

- Published25 October 2018

- Published10 July 2018

- Published3 September 2018