Bloodhound Diary: Do the maths

- Published

A British team is developing a car that will be capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h). Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the vehicle aims to show its potential by going progressively faster, year after year. By the end of 2019, Bloodhound, external wants to have demonstrated speeds above 500mph. The next step would be to break the existing world land speed record (763mph; 1,228km/h). The racing will take place on Hakskeen Pan in Northern Cape, South Africa.

We were all shocked and saddened to hear of the fatal crash of one of our competitors - Jessi Combs.

She was driving the North American Eagle jet car on the Alvord desert in the USA when the accident happened.

A crash like this is incredibly rare. In the pursuit of the Outright World Land Speed Record, there had only been five fatalities since the first record was set in 1898, with the last of them way back in 1962. Now that number is 6. Our thoughts and prayers are with Jessi's family and with the North American Eagle team.

As Bloodhound is now in its final weeks of preparation for our high-speed test session in South Africa, we are reviewing all of our test plans and safety procedures, to make sure we haven't missed anything.

We still don't know what happened to Jessi's car or why it crashed and, in any case, Bloodhound is a very different car from the North American Eagle, with a different team and a different approach, so we can't compare the two.

However, Jessi's accident is a stark reminder that we are working in an unforgiving environment.

In part, that is the point of our high-speed Test session. We need to learn, step-by-step, how to operate in this high-speed arena, before we turn the dial up to supersonic levels for a world record attempt.

More fuel please

To get the car ready for high-speed testing, one of the key modifications for this year has been to add an extra "auxiliary" fuel tank.

Thanks to Jonathan Tubb and Advanced Fuel Systems, the car now has an additional 400 litres of fuel capacity.

It might sound counter-intuitive, but our 500+ mph testing this year will actually use more fuel than a supersonic record run.

Take a moment to think about it, though, and it starts to make sense.

For our testing this year, we are only using the Rolls-Royce jet engine, without the Nammo rocket that we will need to reach supersonic speeds.

As a result, we will be accelerating more slowly, taking longer to reach peak speed (which increases for each test profile).

Longer runs will mean more jet fuel used, hence the need for an auxiliary fuel tank this year.

One obvious advantage of longer, slower runs is that it gives us more time to test the car's handling and stability, as well as the airbrakes, drag parachutes and wheel brakes.

It will also give more data from the hundreds of sensors all over the car and more time to test the onboard control systems.

As the driver, I'm going to be focussed on the obvious "car" bits of performance - the jet engine power levels, speed, steering, suspension set-up, braking systems, and so on.

Airbrake linkages

Equally important will be the vehicle sensors to check that the structural loads and

temperatures are within limits, and that everything else is working as it should.

If there are any obvious failures, then I will get a warning light in the cockpit and abort the run. That's the point at which I need those braking systems to work!

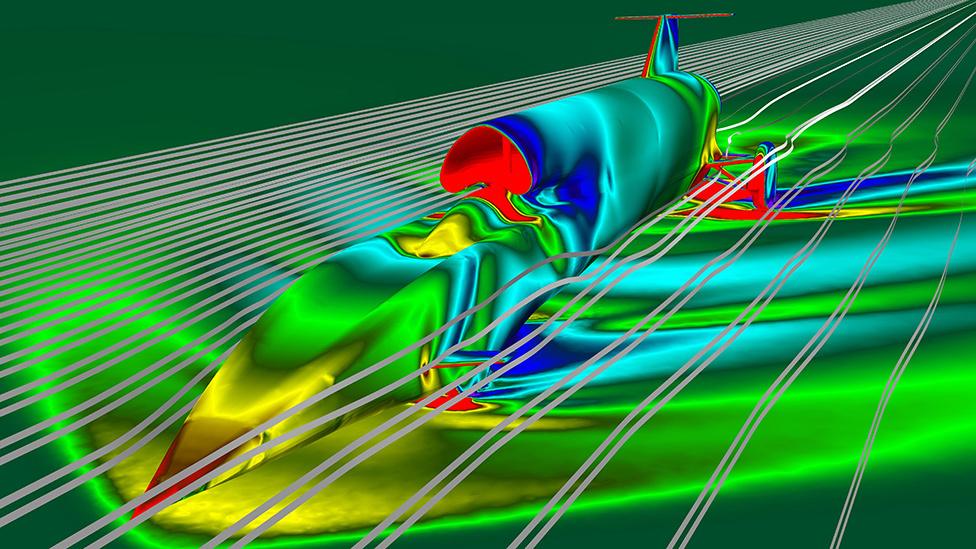

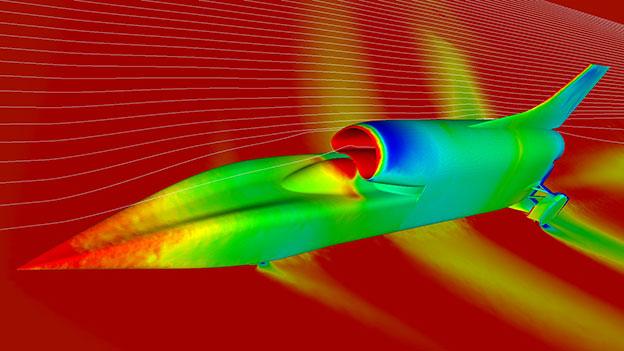

The more interesting analysis will happen after the runs. In particular, the pressure sensors (just over 190 of them) will give us a unique chance to validate the aerodynamic computer models built by Swansea University.

In turn, this will allow us to refine the performance figures and design details (if necessary) for next year's land speed record attempt.

This is perhaps the real benefit of high speed-testing this year - it will give us tremendous confidence in our supersonic record car.

This aerodynamic data analysis is all "geek" stuff, with lots of numbers, but there is some good news for the rest of us.

Swansea University has also developed a computer programme to "picture" the pressure differences across the car every time it runs.

As a mathematician, I love a good set of numbers, but you can't beat a picture for showing you what's going on.

Running on the Hakskeen Pan desert in South Africa this year will also show us how the dry mud/silt surface interacts with Bloodhound's solid metal wheels.

Fairly obviously, the wheels will be supporting the car and providing the lateral grip for steering at slow speed.

As the car speeds up, the grip from the wheels will reduce, before the aerodynamic forces start to take over.

During this transition, I'll be working hard to assess the effects on the car's handling and stability.

Vehicle stability is not the only thing that we need to understand, though. As the car runs over the mud surface, the wheels will throw up a "spray" of dust particles.

This choking thick dust cloud will get sucked into the airflow around the wheels, up into the wheel bays and around the back half of the car.

Bullet proof wheel arch liners

The dust cloud from the desert surface will be pretty violent.

Think about this for a moment: when the car is doing 500mph (800km/h), the bottom of the wheel will be stationary on the ground, so the top of the wheel is doing - wait for it - 1,000 mph (1610km/h) inside the wheel arch.

Yes, that's right, the top of the wheel is travelling at nearly 1.4 times the speed of sound relative to the bodywork around it. That will be a dust storm of truly epic proportions.

If you're wondering why our newly completed front wheel-arch liners look like they are virtually bullet proof, it's because they need to be.

There's a supersonic dust storm headed their way shortly.

As the car gets ready for next month's flight out to South Africa, the various bits of bodywork are being painted in our new white-and-red colour scheme.

The best bit for me was seeing the tail fin finally given it's racing paint work and "flag" graphics, complete with 36,000 names on it.

We owe a huge vote of thanks to those 36,000 people who paid to put their names up there.

We promised you all that one day you would be able to watch your name (and, for a lot of you, your kids' names) racing across the desert at high speed, setting world records.

Thank you all for your patience - the time is finally at hand.

Thank you, 36,000 times

For those of you that are going to follow our testing progress this year, I'm sorry that you can't join us in South Africa.

The high-speed testing is a "closed" session, as there won't be any spectator facilities.

Fear not though. For our record attempt, the Northern Cape Government will be making sure that they can cope with huge numbers of visitors.

If you really, really want to see a supersonic car run (and apparently it's really impressive!), then your chance will come soon enough.

In the meantime, keep watching the Bloodhound website, external and BBC News online. There'll be lots of exciting stuff and plenty of video over the coming weeks.

- Published31 July 2019

- Published10 July 2019

- Published11 June 2019

- Published28 March 2019

- Published21 March 2019